How Country Life helped change the face of modern gardening

George Plumptre examines how Country Life championed the marriage of formal design with natural planting, changing the garden forever.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This article appears in Country Life’s 125th anniversary special commemorative issue, on sale now at all good retailers — or you can buy the issue online from Magazines Direct. You can also subscribe, getting six issues of Country Life for just £6.

It is no coincidence that 1897, the year in which Country Life was founded, can also be seen as marking the birth of the modern garden in Britain. Shortly before, the garden designer J. D. Sedding had written: ‘Everyone who can, now lives in the country, where he is bound to have a garden.’ It came after a number of years that had witnessed a conscious move away from the ‘display’ elements of Victorian gardening, a reaction against what were perceived as excesses — labour-intensive obsessions with unnatural massed displays and showing off exotic plants from all over the world.

Against this background of change, the new Country Life quickly took a leading role in illustrating and promoting a more balanced approach to gardens. Within a short period of time, not least because of the unrivalled photographic library it built up, the magazine assumed a position of influence that it has retained ever since.

Inspired by the more restrained and vernacular Arts-and-Crafts Movement, which celebrated detail over impact and local vernacular over grandiose uniformity, garden designers in the 1890s increasingly adopted a view driven by key principles that emerged during the decade: that a garden should relate directly to its house in both scale and character; that there should be a clear balance between formal architectural features and planting; and that, however grand a garden might be, it should have recognisable human accessibility.

There was a group of key protagonists who made this happen, all working in slightly different styles, but united in their belief in these three principles. They included Thomas Mawson, Harold Peto and, in particular, Gertrude Jekyll and Edwin Lutyens, who were to be closely associated with Country Life in its formative years from 1897. It was their partnership that provided the alchemy of the modern garden, a magical blend of attitude and action whose legacy became embedded in gardens of the 20th century and beyond.

David Ottewill wrote in The Edwardian Garden: ‘The Lutyens and Jekyll garden represents a synthesis of formal layout and natural planting unique in garden art. To his youthful genius for architectural form and geometric invention, she brought a mature understanding of the crafts and an enthusiasm for vernacular and old-fashioned plants, which together produced a succession of enchanting designs, original in conception, perfect in scale and exquisite in colour and material.’

The year of Country Life’s foundation saw the first of the series of new house and garden commissions that the seemingly unlikely couple of a stout, serious, middle-aged spinster and a youthful, ebullient, but inexperienced bachelor, would undertake together in the years to the First World War. They first worked together on Jekyll’s Surrey home at Munstead Wood, where Lutyens designed a new house for her and she planned and planted the surrounding garden.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Their inaugural joint commission was nearby, at Orchards, owned by Jekyll’s friends William and Julia Chance. Like Munstead, the new house designed by Lutyens was built of local Bargate stone, quarried on site. In her affectionate book, Gardens of a Golden Afternoon, Jane Brown wrote: ‘Orchards was the first masterpiece of garden design to spring from the partnership and is especially notable for its unity with the house… not only does the planting blur the outlines of both the house and the terraces and so combine them… both house and garden appear to grow out of the ground.’ In many ways, this assessment can be seen as a blueprint for what garden designers have aspired to ever since. Regardless of what style they are creating or what palette of plants they are using, an underlying unity of house and garden and of hard and soft landscape features has been a universally accepted ideal.

It was their next commission in 1899, Deanery Garden, Sonning, home of Edward Hudson, founder and owner of Country Life, that was to bind Jekyll and Lutyens to the magazine and cement its role as an arbiter of gardening good taste. Hudson had expanded his family’s printing business into publishing and Country Life was his first major venture. The new weekly periodical featured racing and other country sports, but it was also clearly aimed at a female audience. Within a few issues, Notes from my Diary, a fashion column written in breathless style, had been added, as had In the Garden, a column on plants written in a more serious, practical style by Jekyll herself.

Lutyens’s daughter Mary related an endearing memory of Hudson, who became a lifelong family friend. He was ‘a tall man, very kind but unattractively plain… He was very good natured. We had a fire screen in the nursery the bottom part of which could be moved up leaving a gap at the bottom. It was perfect for playing French Revolutions, and Hudson was most obliging at kneeling on the floor and putting his head through the gap so we could “guillotine” him.’

At Deanery Garden, Hudson commissioned a new house and garden from Lutyens and Jekyll on the site of an old orchard, enclosed by brick walls and lanes in the middle of the village. The site is about two acres and became filled with a design of the utmost complexity and yet the finished picture is one of satisfyingly simple harmony. As Miss Brown wrote: ‘The dominant theme… is the interpenetration of inside and outside by means of intersecting axes. The structural geometry of the house is extended outwards, setting up a direct relationship with the garden and thereby making the house look larger than it is, a constant device of Lutyens.’

Part of the old orchard was retained to add a background of naturalness to the garden, which was in part highly architectural. Jekyll ensured that her choice of seasonally shifting plants clothed and softened Lutyens’s patterns of brick and stone and his elegant water features, with varied foliage and shades of colour coordinated with an artist’s skill. Years later, Ian Phillips wrote: ‘The harmony and balanced asymmetry of this whole design, achieved in the early years of the partnership, set a standard difficult to surpass.’

As the 20th century was ushered in, therefore, Country Life had already begun to directly contribute to the development of the modern — or contemporary — garden and to become its most significant shop window, illustrating on a weekly basis a series of gardens ‘old and new’.

A generation later, in 1927, it was to make another significant contribution when it championed the foundation of the National Garden Scheme (NGS) and published the new charity’s first annual guidebooks, The Gardens of England and Wales Open to the Public in aid of the Queen’s Institute of District Nursing, from 1932–39. Today, it continues to champion gardens ‘old and new’ and to showcase them amid the eclectic editorial mix that has always been the magazine’s raison d’être. Hudson would definitely recognise and applaud the current blend of sport, fashion, art, architecture, gardens and rural affairs he initiated 125 years ago.

George Plumptre is chief executive of the NGS

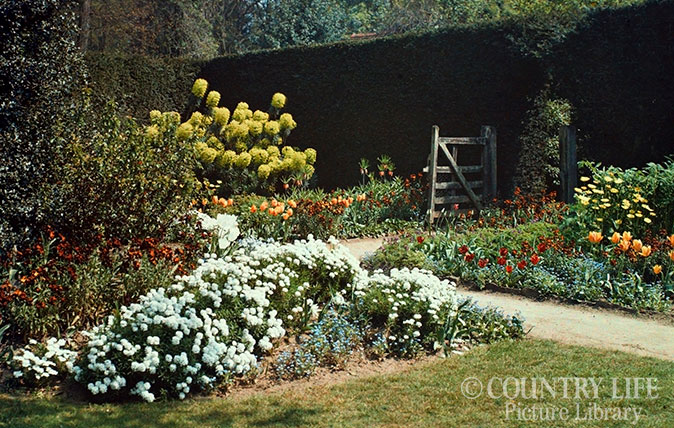

Credit: Gertrude Jekyll's garden at Munstead Wood - photographed in 1908 (©Country Life Picture Library)

15 colour photographs from 1912 showing Gertrude Jekyll’s garden at the height of her fame

Mark Griffiths: Why gardening is vastly richer, wider and deeper than in Gertrude Jekyll’s day

Gertrude Jekyll loved bergenais, but she'd be the first to agree that the variety around today far outshines what was