It's a perfect storm for the revival of eclecticism, and we're in the middle of it

In design, periods of purism are often followed by a dramatic new mood. Now, the scene is set for an exciting revival of eclecticism.

The interior designer Chester Jones is known for conjuring rooms that feel both classic and modern by deftly integrating furniture, art and textiles of different eras and genres. Two tenets underpin his approach; one is that spaces shouldn’t reflect a strong imprint of the designer. ‘A sense of the individual identity is highest on my list of priorities,’ he says, ‘good interior design is simply the background.’

The other is that interiors should evolve; he believes that static interiors date too quickly. ‘Everything changes — the values held firm at one point in our lives are later questioned and new ideas take hold. Likewise, the things we collect should create a narrative about us and change as new interests develop.’

As a result, his rooms demonstrate a varied taste in art and furniture, all of which are chosen either for their aesthetic strengths or personal resonance, rather than slavishly adhering to any historical period. ‘Being faithful to a particular period in history might look wonderful at first, but then it becomes stuck in that time.’ Chester believes the role of the designer is to help clients choose pieces of art and furniture, leaving room for individual interests and idiosyncrasies. ‘If things become too familiar, one ceases to notice them. Our role is to attempt to make new relationships between seemingly disparate things.’

Chester’s vast knowledge of both antique and contemporary art is crucial to the success of the rooms he designs. Their composition is aligned with how an artist might address an artwork, considering light and shade, scale and space, texture and colour. In the sitting room of a house he designed in Hampstead, north London, for example, there’s a balance between architecture and contents achieved with paintings and furniture of a compatible weight and scale, but different aesthetics. The result is a highly considered eclecticism.

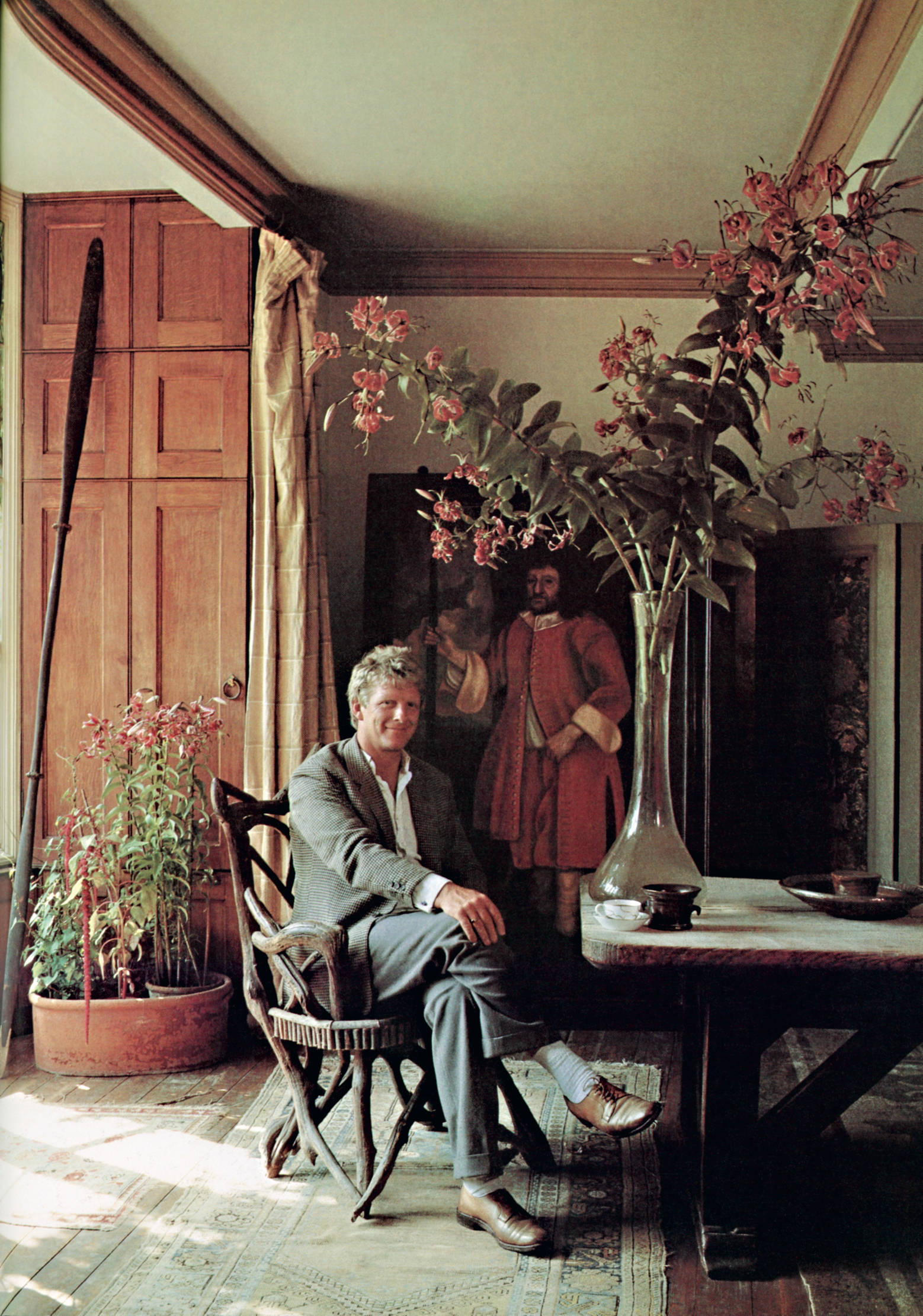

Antique dealer and collector Christopher Gibbs loved exquisite furniture and works of art, but also had a rare gift for finding beauty in the ordinary and the obscure — and his influence had a lasting impact on classic English interiors. Among his clients, who ranged from Jacob Rothschild and John Paul Getty to Mick Jagger, he demonstrated an esoteric brand of anti-decoration. Writing about his work in The New York Times, Christopher Mason noted: ‘The magic is in the mix of masterpieces and oddities — like an assemblage of refined and wild-card house guests who mysteriously combine to create the ideal convivial country-house weekend.’

Christopher Gibbs, one of the most influential antique dealers of his generation.

Many agree that Gibbs was responsible for glamourising antiques in the 1970s and 1980s. Timing was on his side; he spent his formative years witnessing the post-war slump, which ensured that the contents of many of Britain’s great country houses became readily available. Yet his work was also informed by an innately intuitive eye and a depth of knowledge gained through voracious reading. In London, he curated a succession of shops filled with beautiful, unexpected pieces with little in common except a beguiling beauty that celebrated eclecticism.

The late antiques dealer and decorator Robert Kime was known for his ability to decorate with a harmonious blend of antique furniture, ceramics and artworks. Sourced from far and wide, they would sit contentedly alongside elegant — although not necessarily expensive — pieces. It was his great love of textiles that set his interiors apart, however. During frequent trips to Turkey, Uzbekistan and Egypt, Kime brought back charming, battered tent hangings, suzanis and embroideries, which he would use to upholster chairs, drape over tables or on the backs of sofas. He had an approach that is difficult to distil and define, says Christopher Payne, who worked with him for many years. ‘If an object or a painting had an atmosphere or a romance, it didn’t matter about provenance.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Another designer known for her ability to assemble seemingly disparate pieces with dramatic impact is Anouska Hempel. Raised in New Zealand and Australia, she arrived in London during the 1960s and worked as an actress before going into design. She opened the doors to Blakes in South Kensington, the world’s first boutique hotel, in 1978. Her visionary approach, where no room was the same as the next, thanks to a highly eclectic approach, juxtaposing styles and artefacts from different periods and geographies—in particular the Far East—resulted in a distinctive, refined Bohemian style.

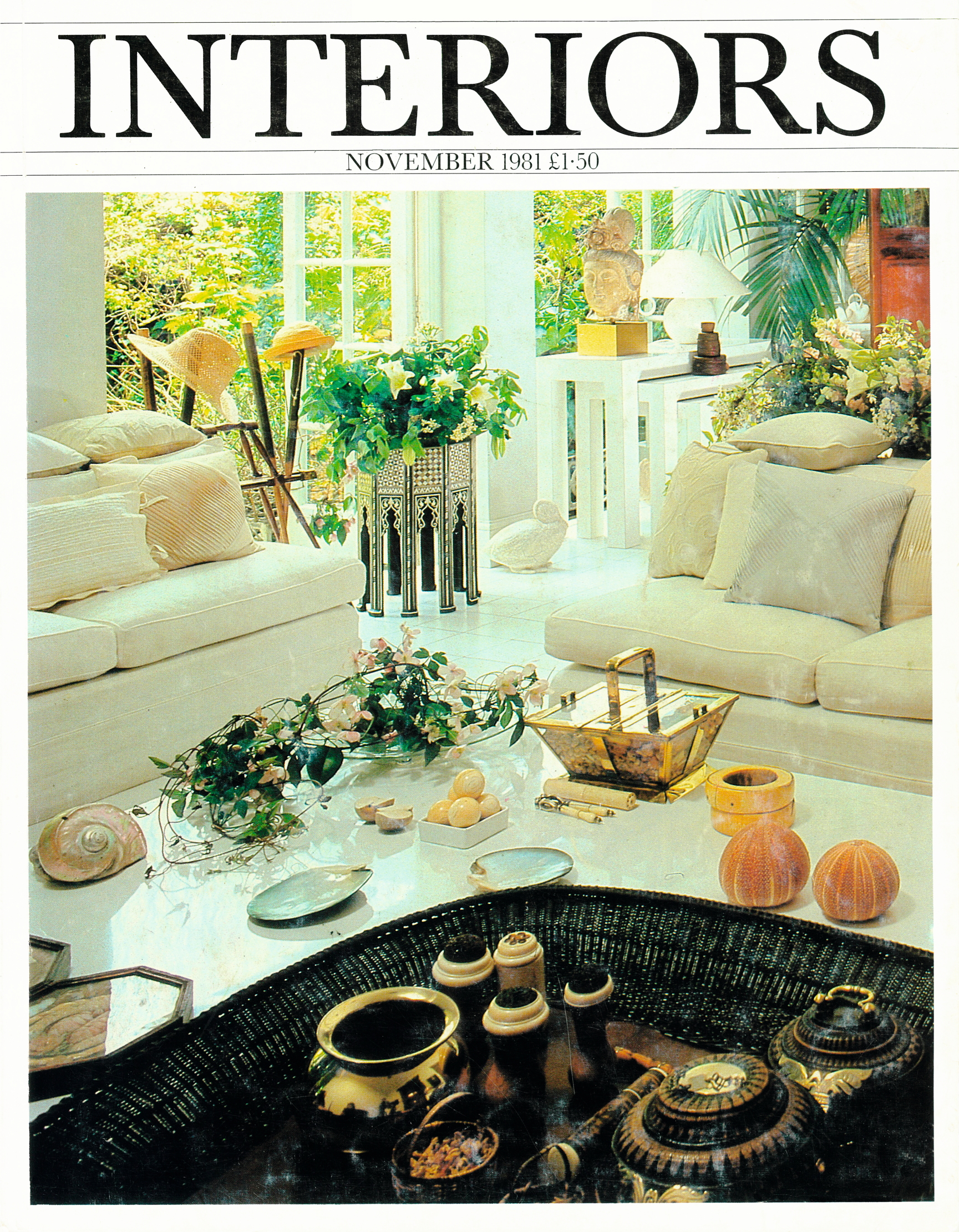

Anouska Hempel’s home featured on the first ever cover of Interiors magazine in 1981.

The hotel soon became a magnet for actors and rock stars attracted by its intimate and exotic mood. Her work also demonstrates the timelessness of eclecticism; a photograph of the sitting room of her London home that featured on the cover of the first edition of Interiors magazine in November 1981 looks as freshly elegant today as it did back then.

A designer who has had a similarly transformative impact on the world of hotel design is Kit Kemp, co-founder and creative director of Firmdale Hotels. Working with her husband, Tim, she opened the Dorset Square Hotel, Marylebone, London NW1, in 1985 and the couple now has a number of highly distinctive hotels in both London and in New York.

Kit’s approach to eclecticism oscillates around a rare ability to blend contemporary art and craft with pieces from a wide array of aesthetic disciplines; folk, applique and furniture inspired by the 18th century to create vibrant, colourful spaces. ‘I’m not a purist and very much believe in imperfect interiors,’ she explains. ‘A room should never feel as if it’s been decorated in a single day. Lots of very tasteful rooms look elegant and clean, but being in them is like living in a country with no culture.’ Echoing Chester's belief, she adds: ‘A room should tell a story of evolving time and the character of the owner. That’s when the magic starts.’

Kit’s contribution to interior design is about more than simply creating an aesthetic, however: it’s also about empowering those around her with the confidence to find things that they love and to use them to create their own joyful spaces. This approach brings authenticity to a room. ‘We can’t all inherit wonderful things,’ she says. ‘It’s about finding things you like and letting them speak to each other in a surprising way by trusting your instincts to mix old furniture with new fabrics. Covering an old club fender or an armchair in a new fabric will look fabulous and introduce character.’

The drawing room of a London townhouse designed by Kit Kemp, the creative force behind a number of hotels in London and New York.

Increasingly, the work of these champions of eclecticism is being noticed by a younger generation of collectors and designers. ‘In many ways, this shift was inevitable,’ says Michael Diaz-Griffith, author of The New Antiquarians: At Home with Young Collectors (Phaidon) who leads the Design Leadership Network and joined Country Life’s Huon Mallalieu and the interior designer Henriette Von Stockhausen at a discussion on eclecticism at this year’s Treasure House Fair.

‘Social media serves as an endless visual archive, exposing younger audiences to the full sweep of design history every time they open their phones. At the same time, millennials and especially Gen Z are drawn to the romance, whimsy, and tactile depth of the non-digital realm, from print magazines and “archival” fashion to the vintage and antique objects they are increasingly collecting. For young design enthusiasts, Modernism is simply one style among many, whereas traditional design — particularly hand-crafted works — feels alluringly exotic.’

None of this should be terribly surprising, he adds, for periods of purism are inevitably followed by waves of eclecticism. ‘Those who experienced the antiques boom of the 1980s and 1990s, and the subsequent downturn in the 2000s and 2010s, for example, the revival of interest in collecting and eclectic decoration seems almost too good to be true. But stranger things have happened. Few people would have anticipated the Young Fogies of the 1980s.'

In today’s highly pluralistic world, dramatic swings in taste are even more likely to happen — and they happen fast. We’re in the middle of one right now and it’s the perfect storm for a revival of eclecticism.’

This feature originally appeared in the October 8, 2025, issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe'