Exhibition review: 'Cornelius Johnson: Charles I's Forgotten Painter' in London

Huon Mallalieu reassesses an unsung master of 17th-century portraiture.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

One of my most treasured books is The Picture Collector’s Manual, an 1849 dictionary of artists by James R. Hobbes. I value it not for its accuracy, but because my copy belonged to F. G. Stephens, the art critic and one of the original Pre-Raphaelite brethren. Also, it gives a good idea of how Victorians rated artists, often very differently to us.

As the National Portrait Gallery’s small but fascinating show devoted to Cornelius Johnson describes him as ‘Charles I’s Forgotten Painter’, I wondered what Hobbes might have to say. He has 2 1⁄2 references: ‘Janssen (Cornelius) born in Amsterdam, 1590; came to England in 1618, and painted several excellent portraits of James I and family, and also of the principal nobility’; ‘Johnson (Cornelius)—see Janssen’; ‘Keulen (James Van), born in England of Dutch parents; was eminent as a portrait painter… previous to the arrival of Vandyck…died 1665.’

This provides us with two of the three reasons for Johnson’s later obscurity. He worked under a confusion of names and his career was stymied by the arrival of Van Dyck in 1632. As far as England was concerned, it was finally killed off by the Civil War. In 1642, he left for the Netherlands, where he signed ‘Cornelius Jonson Londini’ until the 1652 war with England, when he switched to ‘van Ceulen’. He died at Utrecht in 1661.

Despite believing him to be two distinct artists, and getting his dates wrong, Hobbes was right on several essential facts. Johnson was actually born in 1593 in London. His family were German-Flemish Protestant refugees stemming from Amsterdam and Cologne (Ceulen or Keulen). He trained in the northern Netherlands, presumably before 1619, when he is again recorded in London, and perhaps also in the studio of Marcus Gheeraerts II, official portrait painter to James I’s queen.

On his return to London, Johnson settled in Blackfriars, which, like Spitalfields, was attractive to Huguenots and other incomers because it was just outside the City boundary and the jurisdiction of the Guilds. The miniaturists Isaac and Peter Oliver and Abraham Cooper lived there, Van Dyck was to join them and, later in the century, the clockmaker Thomas Tompion, up from the country, established himself within 100 yards of Johnson’s old house. During the 1620s and early 1630s, Johnson did very well indeed, particularly among successful lawyers—the Temple is immediately west of Blackfriars — such as Lord Keeper Coventry, whom he painted several times. In December 1632, he was app-ointed ‘his Majesty’s servant in ye quality of Picture Drawer to his Majesty’, but he was given comparatively few royal commissions, as, in April, Van Dyck had arrived. Ever the businessman, Johnson painted admirable miniatures, unusually sometimes in oil, as well as large portraits; he was willing to collaborate with other artists and even to supply copies of Van Dyck’s royal portraits.

No doubt it was also sound business sense that led him to build up a country clientele beyond City and Court circles, principally among the gentry of Kent, and this is why there are still numerous portraits by him to be found in English country houses. Once one has seen a few of them and got one’s eye in, Johnson’s work — or, in weaker cases, that of his assistants — becomes very recognisable.

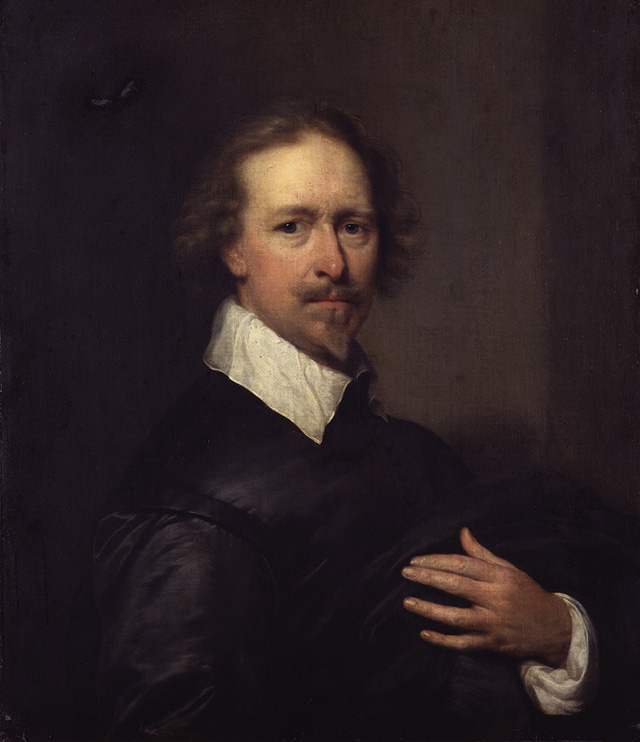

Early on, he liked to paint bustlength portraits set in feigned stone ovals. He gives many sitters large, roundish eyes, which may make them look younger. He had a number of stock poses, which were evidently popular, but lack the Baroque snap and movement Van Dyck had brought back from Italy. Above all, he was a masterly painter of clothing, whether the sumptuous dresses, lace and jewels of his Court ladies, or the discreetly expensive black favoured by many sitters as the clouds of Puritanism covered the land. His handling of black silk is as good as a signature.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition gives him just one small room, with one of his masterworks on a nearby wall next door—the large group of Lord Capel and his family set before the garden of Hadham Hall, their Hertfordshire seat. However, this is enough to give a very fair idea of his many strengths, and alas, his subordination to Van Dyck.

The show is accompanied by a really good book by the curator, Karen Hearn (Paul Holberton £14.95). She has managed to untangle all the knots of nationality and nomenclature and has brought him back to take an overdue bow. ‘Cornelius Johnson: Charles I’s Forgotten Painter’ is at the National Portrait Gallery, St Martin’s Place, London WC2 until September 13 (020–7306 0055; www.npg.org.uk)

Huon Mallaleiu writes on fine art and antiques for Country Life magazine