Simon Jenkins: 50 years of saving Britain's buildings, from triumphs and disasters to the great country house we bought for £1

In 1975, a new organisation was set up with the express aim of saving Britain's most beautiful and historic buildings from the wrecking ball. How has SAVE fared in the 50 years since then far?

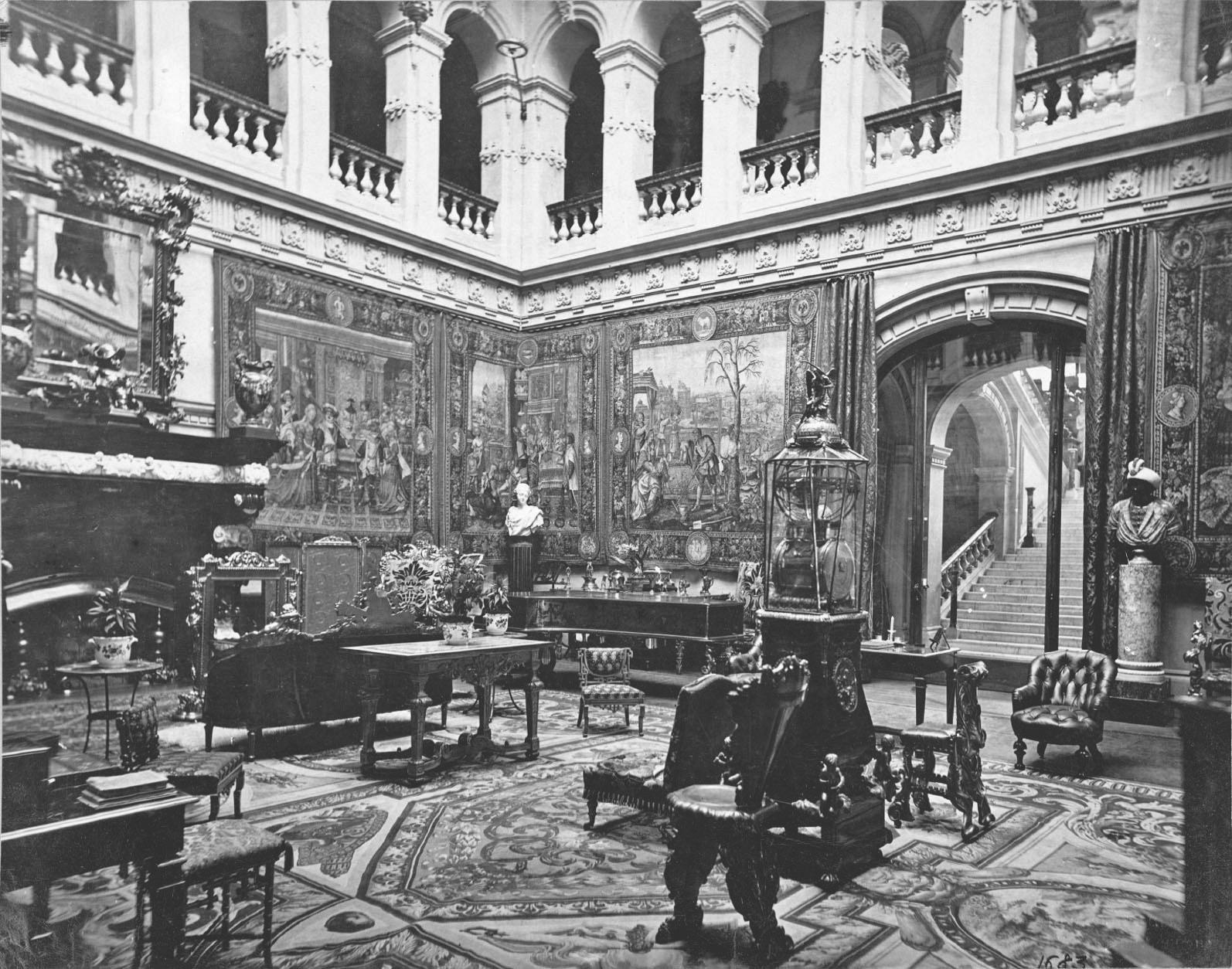

Visitors left the gallery with tears streaming down their faces. That is what Sir Roy Strong, director of the V&A Museum, recorded in his memoir of the ‘Destruction of the Country House’ exhibition in 1974. No wonder The Observer called the V&A show ‘the most emotive, propagandist exhibition ever to grace a public museum’s walls’. Sir Roy declared that ‘no other country has been party to such artistic destruction in a period of peace’. By the time it was staged, British buildings were finally being listed for preservation. The National Trust was taking ownership of more each year. Yet it was reported that one house a week was still being lost. Hidden behind walls and up drives, the massacre continued. There was no one to love them and few to care.

The mid 1970s saw a counter-revolution in attitudes to architecture. The previous decade had marked the partial collapse of Modernism as the guiding ideology of British town planning. The teaching of its figurehead, the Swiss-born Le Corbusier, that old buildings were by their nature obsolete, still ruled most architecture colleges and planning departments. However, London’s Whitehall, Soho and Piccadilly Circus had at least escaped demolition. The residents of Covent Garden revolted against being evicted to make way for a second Barbican. A giant Motorway Box encircling central London was abandoned.

Fig 2: The Grimsby Ice Factory, Lincolnshire, built in 1898-1900, supplied the town’s fishing industry, producing 1,200 tons of ice a day at its peak in the 1950s. It remains on the Heritage at Risk Register.

More important was a sense that the British heritage was no longer a private domain to be sacrificed to progress and personal gain. Heritage belonged to the nation. In the past, it had been mourned by such worthies as the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) and specialists such as the Georgian Group and Victorian Society. Yet they had behaved with the effete decorum of cultural undertakers. The message of the V&A was that this was not enough. A national treasure was being destroyed. It was a call to arms.

A group of young writers and historians, some working for Country Life, had been involved in creating the exhibition, including John Cornforth, John Harris and Marcus Binney. Together with some architectural journalists, they decided to seize the moment created by the V&A show to adopt a more aggressive approach. I was one of their number and, at the start of 1975, we gathered in the Pimlico basement of Mr Binney, long SAVE’s guiding personality, and toasted the foundation of SAVE Britain’s Heritage.

Fig 3: Liverpool Street Station, London EC2, photographed during lockdown. Both the interior and the setting are now threatened by grossly insensitive redevelopment.

The strategy was specific: to save buildings by mobilising shame through publicity. The weapon was the press release, galvanised by the newly arrived medium of the fax. The rattling sound of that machine could bring the most somnolent newspaper office to life. As threatened sites were by definition local, it also gave the local press something to bite on.

We had some early disagreements. Should we risk ridicule by saving a Victorian lavatory in Herne Bay? The answer was yes — ‘Spend a penny for Ye Olde Loo’ — and it put us on front pages. Should we have members? No, they only take up time. Were we about elite buildings alone or were we also concerned with humble streets, mills and churches? Were we Modernists? A number of us later spawned the Thirties Society after a row with the Victorians as to when ‘Victorian’ ended. It was later renamed the Twentieth Century Society.

Above all, we felt that saving buildings had to go beyond writing fierce letters to The Times. It should involve the law, commissioning alternatives, seeking rescuers and, Mr Binney was adamant, becoming owners ourselves in emergencies. We ended up buying Barlaston Hall near Stoke, Staffordshire, for £1 and setting up a trust to save Castle House in Bridgwater, Somerset.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Barlaston Hall was saved, and is currently looking for a new owner for rather more than £1: Jackson-Stops have it listed at £2.895m.

I feared at one point we might end up owning Battersea Power Station in London (Fig 4).

There is no doubt we were successful. Although it is hard to claim credit when others share in a victory, SAVE played a major role in halting the demolition of the Battersea and Bankside power stations in London in 1979.

Fig 4: Battersea Power Station became a much-loved London landmark. This photograph shows the roofless ruin, at a time when its future was still in doubt. The subsequent development has saved, but also, from some angles, swamped, the original building.

It was in the lead in rescuing from ruin both Wentworth Woodhouse, South Yorkshire (Fig 1), and Dumfries House, Ayrshire (Fig 5), plus Liverpool’s Albert and Stanley Docks (Fig 7). There followed over the years, in London, Paddington station roof, Whitehall’s Richmond Terrace and Georgian houses in the Strand, as well as Anglia Square in Norwich, Norfolk, and 400 terrace houses in Liverpool’s Welsh Streets (Fig 10). We even saved the historic wind tunnels of what has become Farnborough Air Museum, Hampshire.

Fig 5: Dumfries House, Ayrshire, was preserved with SAVE’s involvement.

The list of ‘saves’ now runs into hundreds. Before fighting for the warehouses of Grimsby’s extraordinary fish market in Lincolnshire (Fig 2), SAVE saved Smithfield Market in east London in 2014 by marching on Parliament with 100 protesters dressed, or undressed, as Lady Gaga (Fig 8). Both worked. Generic reports were also produced, regularly cataloguing the fate of Victorian churches, Board Schools, northern mills and town halls.

There were undoubted failures. The Rothschild pile of Mentmore in Buckinghamshire was stripped of its contents (Fig 6), as was Shropshire’s Pitchford Hall (Fig 9). Today, the former still stands empty, but the latter has returned to family ownership (Country Life, November 6, 2019). The Georgian London Docks in Wapping were demolished by a minister, Peter Shore, to make way for Rupert Murdoch’s new printing plant. The saddest failure was the City of London’s refusal to restore the Baltic Exchange, bombed by the IRA in 1992, in favour of the Gherkin.

Fig 6: The contents of Mentmore in Buckinghamshire, were dispersed.

Despite a long battle against an intransigent council, Ayr’s great Station Hotel in Ayrshire has not been saved. This was despite years of campaigning, with local and press support, an alternative rescue plan being commissioned and meetings with the council and MSPs. Eventually, the council leader resigned amid doubts over demolition contracts. The most recent defeat followed a victory at a public inquiry to save the M&S building in London’s Oxford Street. New to office and desperate to bolster her image as ‘pro-growth’, Angela Rayner personally overturned the inquiry decision and allowed demolition. That so many heritage decisions depend on ministerial whim is appalling, but, on a rough estimate, SAVE has been victorious 80% of the time.

In 1989, SAVE opened its Buildings at Risk Register, 10 years before Historic England thought of doing the same. The list now features some 1,400 entries of historic properties in various stages of neglect, beseeching well-intentioned buyers to step forward. Critical so often has been liaison with local individuals and groups, whose efforts can be galvanised by national recognition. Wars are frequently with the members of local councils, who simply fail to see the value of what is in their care or under their jurisdiction.

Fig 7: SAVE has played an important catalysing role in such outstanding projects as the restoration of Liverpool’s Royal Albert Docks.

Today, the great houses that sparked the conservation movement in the 1970s have largely been secured. The tumbling ruins of the 1950s and 1960s are homes to rock stars and private-equity tycoons. The pages of Country Life are filled with palaces that 50 years ago would have lain hidden in rubble and ivy. The Historic Houses website testifies to the hundreds now open to the public.

Battle continues, largely over buildings in the care of impecunious councils and utilities, or at least under their responsibility. The railway scandals of the 1970s and 1980s, such as the destruction of Derby’s Trijunct Station and London’s Broad Street, or the threat to Ribblehead Viaduct in North Yorkshire, are mostly past. The forming of the Railway Heritage Trust by one of SAVE’s founders in 1984 turned British Rail from demolisher to mostly restorer. Stations from Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk to Peckham Rye in south-east London took on a new life.

Fig 8: The singer Lady Gaga retweeted a picture of her doppelgängers fighting successfully to save Smithfield Market from hugely destructive redevelopment.

Noticeable was the role of the now much-abused planning system in the conservation process. In case after case, publicity proved insufficient. Developers and their often co-conspirators in planning offices were immune to shame. SAVE’s approach had to be complex. We had to shout, to sue and, if necessary, to substitute one plan with our own.

Proving a particular council’s failure to properly consult or co-operate became a standard method of postponing demolition, giving SAVE time to summon a valiant corps of pro-bono lawyers. This enabled the calling in of allies and the search for possible alternative uses for a threatened building. The effort put into these campaigns by a tiny staff could be awesome.

SAVE has never received a penny of public money to fight its legal battles. We had to appear before courts and public inquiries against developers dripping with cash. The absence of constructive initiative or even help from local councils was often glaring, fuelled by the austerity now forced on them by central government. Some councils could at least be bullied or shamed into assistance: witness Nottingham’s Wollaton, Cardiff’s Castle and Newport’s Tredegar. Some failed. Manchester’s Heaton was and is a disgrace. Derbyshire had a terrible record, its councils disposing of houses in their care at Glossop, Breadsall, Chaddesden, Etwall and Darley.

Fig 9: The contents of Pitchford Hall, Shropshire, were sold up despite SAVE’s efforts, but the family itself has come back and the house is now secure as a private home.

Evident, too, was the readiness of sympathetic judges to grant stays of execution. So often in these sagas, it was individuals stepping forward at the last moment that turned disaster to triumph. Developers such at Kit Martin, Richard Broyd of Historic House Hotels and the always present, always wary National Trust were there in times of distress. Battles to save Stoneleigh Abbey in Warwickshire or Tyntesfield in Somerset were on a knife edge, but at least were won.

Going through the monthly lists, I still sometimes wonder if the V&A exhibition was quite the triumph we all suppose. Yes, it did save the great houses, but what of the rest? What of the churches, the factories, the big stores, the seaside piers? What of the terraces of Victorian houses still being destroyed because the dogma of British planning remains stuck in Corbusian mode, hostile to the street rather than the block? The British street is still a threatened construct.

I used to think that, for all the crises that inevitably swirl round Britain’s historic buildings, their security did at least improve from one year to the next. There were friends and allies in high places who were fighting our battles behind the scenes. We could rely on listing and conservation-area officialdom to protect the cause.

Fig 10: The forced clearance of streets in Liverpool under the so-called pathfinder scheme became a scandal. Pictured is one of the restored Welsh Streets in Toxteth.

I am beginning to have doubts. At least three London boroughs, the City of London in Fleet Street, Westminster at Paddington and Tower Hamlets at Whitechapel have flagrantly flouted their own conservation areas and been allowed to do so by superior authorities. The concept of ‘growth’ as requiring a reduction rather than undoubtedly urgent planning reform is potentially disastrous. Adaption and retrofitting of existing buildings remains subject to VAT, whereas demolition and carbon-intensive rebuilding are VAT-free. This laughs in the face of the Government’s net-zero pledge.

The role of local people — vital to SAVE’s work — in planning their environments is being weakened by the Government’s disempowering of local councillors. This will make it incomparably harder for volunteers to object to local harms. Council finances, often crucial to keeping historic buildings in shape, are debilitated. Labour has identified the beauty of the built environment with ‘blocking’ and ‘nimbyism’. The public domain today seems more philistine than it was.

This is evident in SAVE’s current casebook. The proposed erection of a skyscraper over Liverpool Street Station (Fig 3) defies belief, as did the skyscraper planned to tower over neighbouring Bevis Marks synagogue. Councils throughout London and the provinces now regard towers that threaten the setting of historic areas as a sign of civic virility. This is to a degree inconceivable in most, if not all, other European countries.

Most at risk are the modest buildings that give charm to urban neighbourhoods, that give them context. British architecture has never been good at context. In under-protected Wales, the listed Corbett Arms Hotel, prominent in Tywyn’s town centre, is about to collapse, with its Gwynedd council looking on with glee. Likewise at risk are an old colliery engine house near Caerphilly, a hotel in Trafford Park, Manchester, and Moggerhanger House in Bedford.

As the American Jane Jacobs said of the buildings of her beloved New York, each case may seem trivial in itself, but the totality of cases is all. SAVE has always been about the totality of the trivial. I have a feeling it will be needed for ever.

Visit the Save Britain's Heritage website for more information

Simon Jenkins is a journalist and author who began his career at Country Life before going on to serve as the political editor of The Economist and editor of The Times.