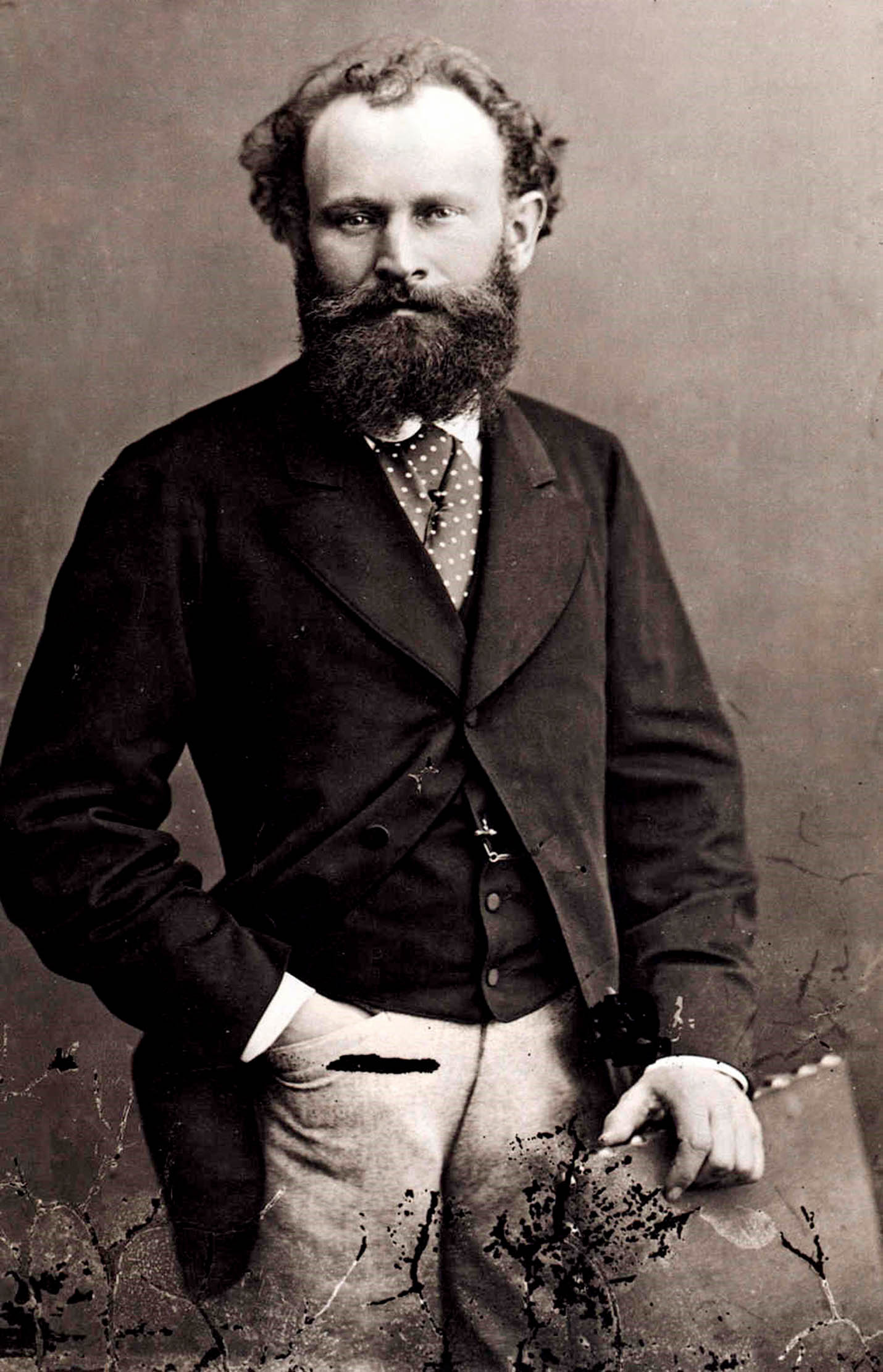

In Focus: Edouard Manet, the man who shocked France with nudity, executions and everyday life

Edouard Manet relished goading the French establishment, yet longed for the artistic recognition that came mostly after his death, laments Michael Prodger.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

All painters must start somewhere, but Édouard Manet — who is the subject of a new exhibition at the National Gallery in London — found a particularly unusual route into his career. As a young man, his father ignored his wish to become an artist and forced him to join the merchant marine as a first step to becoming a naval officer. On a voyage to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the sailors noticed that their cargo of Dutch cheeses had been damaged by seawater. ‘The rinds had become bleached, and that was a worry,’ Manet later recalled. ‘I volunteered to put matters right and, conscientiously, with a shaving brush, I touched up the pale corpses.’ This bit of sleight of hand, he said, ‘was my beginning as a painter’.

Fortuitously — one wonders how hard he tried — Manet failed his naval exams and swapped the shaving brush for the paintbrush, but he never became shy of the unorthodox. After Manet’s death, the Impressionist Camille Pissarro wrote: ‘Manet, great painter that he was, had a petty side, he was crazy to be recognised by the constituted authorities, he believed in success, he longed for honours… he died without achieving his desire.’ But then, he had spent decades as a provocateur: he goaded the art establishment by refusing to paint in the approved manner; he outraged the bourgeoisie with his paintings of all-too-real nudes; he prickled with attitude; he was a flâneur with a penchant for yellow trousers; and a mentor to the younger rebels of the Impressionist circle. If he wanted acceptance, he had a strange way of going about it.

This contrarian side to his nature was evident in one of his more grandiose statements. ‘Everything is mere appearance, the pleasures of a passing hour, a midsummer night’s dream,’ he declared. ‘Only painting, the reflection of a reflection — but the reflection, too, of eternity — can record some of the glitter of this mirage.’ Nevertheless, at the heart of his art is the modern world, albeit sometimes filtered through the influence of artists he admired, such as Velázquez or Frans Hals.

He did, on occasion, paint ‘the reflection of a reflection’, as in his early homage to the Spanish golden age The Spanish Singer, 1860, and paintings of beggars and gypsies, but there is rarely any doubt that his real topic is Parisian life in the second half of the 19th century. Indeed, it was because he treated it as tangible rather than as a mirage that he found himself at the centre of so many controversies.

Initially, Manet seemed biddable. He trained under the history painter Thomas Couture and travelled around Europe to broaden his exposure to the great painters of the past. His early works were accepted for the annual Paris Salon, the officially sanctioned showcase for French art, and received a degree of acclaim, although his loose, open style of painting ran contrary to accepted academic style.

In 1863, however, he painted two works that were to cause outrage, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia. Both showed naked women — the distinction between naked and nude was important here — and seemed to be calculated attacks on conventional morality. Both were based on Renaissance models — a Raphael and a Titian respectively — but subverted them. The former showed a naked woman sitting in an outdoor setting between two fully clothed men with another unclothed woman in the background, the latter an interior with a bare woman on a bed attended by a black servant.

The central figures in each painting stare out, unrepentant, challenging and anything but coy, and viewers took this as an affront. These women, especially Olympia (a name traditionally denoting a prostitute) were not decorous Classical nudes — they illustrated no tale by Ovid, but were unidealised flesh and blood. Olympia’s status as a demi-mondaine was made all the more obvious by the orchid in her hair, the choker at her throat, the black cat at her feet, a slipper dangling from one foot — all symbols of the courtesan. The viewer, indeed, stands in the position of a client as he enters her boudoir.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Such was the furore that the picture was almost torn down by irate Salon goers. ‘If the canvas of the Olympia was not destroyed,’ recalled a friend of Manet’s, the future Arts minister Antonin Proust, ‘it is only because of the precautions that were taken by the administration.’ In the face of attacks on both paintings’ immorality and vulgarity — and their perceived insult to the traditions of Old Master art — Emile Zola, one of Manet’s great supporters, came to his defence: ‘When our artists give us Venuses, they correct nature, they lie. Édouard Manet asked himself why lie, why not tell the truth; he introduced us to Olympia, this fille of our time, whom you meet on the sidewalks.’ This appeal to honesty and logic had little effect.

Even before the criticism and despite his hope that he would conquer the Salon, Manet had started to exhibit at the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Rejected), an alternative forum for painters established when the ultra-conservative Salon selection committee turned down more than half of the paintings submitted in 1863. It became a place associated with avant-garde art, although where to exhibit remained a concern for Manet.

When he was rejected by the Exposition Universelle of 1867, he spent, to his mother’s horror, a large proportion of his inheritance on hiring a space across the road from the exhibition and showing 50 of his own paintings there. The general response was far from favourable. An irked Manet lambasted his hostile critics: ‘No one knows what it feels like to be constantly insulted. It sickens and destroys you. The fools! They’ve never stopped telling me I’m inconsistent; they couldn’t have said anything more flattering.’

Manet’s notoriety and his innovative painting style, with its use of black outline and vigorous handling, made him a figure of interest to the younger generation. He was adopted by the artists who would go on to become the Impressionists. Initially, he and Monet didn’t hit it off — Manet thought the younger man was appropriating his technique and trading on his name, as the painted signature ‘Monet’ was confusingly close to ‘Manet’. They soon became close, however, and Manet took on the role of mentor, sympathiser and aspirational figure to the Impressionists. Nevertheless, he refused to exhibit with them, preferring always to be his own man.

Manet’s private life further buffed his outsider allure. He was close to the Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot — indeed, they might have married had she not wed Manet’s brother Eugène instead — and, in 1869, he took on the well-connected artist Eva Gonzalès as his only pupil. She was to die aged 34, six days after Manet’s own death. More titillating, however, was the fact that, in 1863, he had married Suzanne Leenhoff, a Dutch piano teacher hired by his father to teach his boys music. She was probably also his father’s mistress and had a son, Leon Leenhoff, who may have been fathered by either of the Manets.

For all his attractiveness and gregarious nature, Manet’s focus was above all on the difficulties of painting. Modernity fascinated him and he believed — not always compatibly with his musings on painting as capturing a ‘midsummer night’s dream’ — that ‘one must be of one’s time and paint what one sees’. So he painted the crowds listening to music in the Tuileries Gardens; his writer friends Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé and Zola; American Civil War battleships skirmishing off Cherbourg, thousands of miles away from home waters; the races at Longchamp; the body of a man who shot himself in the chest; the execution of Emperor Maximilian in Mexico; and, most famously, a bar at the Folies-Bergère.

Whatever their topic, the majority of his paintings were misunderstood by the critics and that hoped-for place at the heart of the official art world remained elusive. To add to his woes, Manet’s health began to decline, too. He developed rheumatism and his legs became paralysed — the result of syphilis — and, in 1883, his left foot turned gangrenous and he had it amputated. He died 11 days later aged only 51.

Some years later, the dealer Ambroise Vollard asked a group of younger painters where they thought Manet’s importance lay. It was an easy question to answer: he was, they said, ‘a veritable prophet in his day’, the first painter to offer a challenge to ‘a period in which the official art was merely fustian and conventionality’.

‘Discover Manet & Eva Gonzalès’ is at The National Gallery, London WC2, from October 22–January 15, 2023 — www.nationalgallery.org.uk

Credit: David Milne, Tent in Temagami, 1929, Collection of the Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound, Ontario, bequest from the Douglas M. Duncan Collection, 1970. © The Estate of David Milne

In Focus: The Canadian hermit's work that is a dystopian alternative to Monet

Canadian artist David Milne moved from city to country, eventually ending up as a hermit in a remote part of

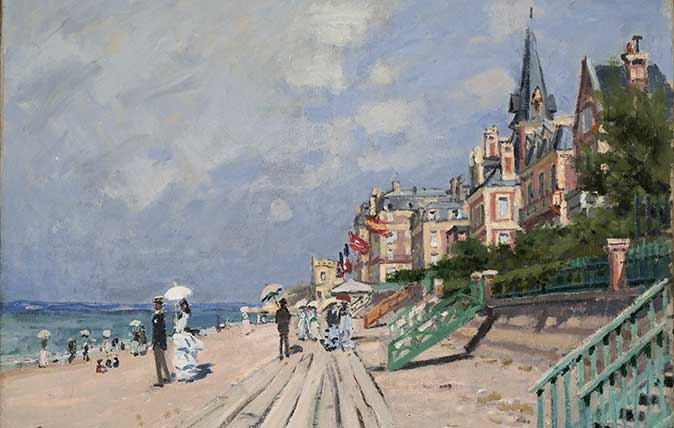

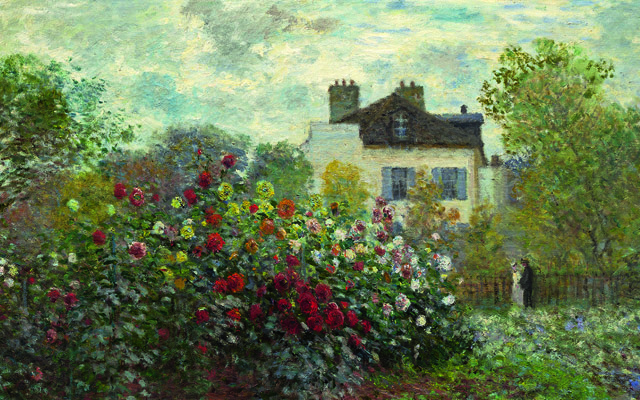

In Focus: The paintings which show Monet's genius for architecture as well as nature

Think of Monet and you think of reflections and nature, but his works included huge amounts of architecture and other

In Focus: The French collection of the extraordinary Wilhelm Hansen, Monet and Manet to 'a wall-full of Pissarros'

Caroline Bugler finds much to enjoy at the Royal Academy’s show of 19th-century French art on loan from Wilhelm Hansen's

Exhibition review: Inventing Impressionism at the National Gallery, London

Louise Nicholson lauds the dealer who put the Impressionists on the map.

Michael Prodger is a senior research fellow at the University of Buckingham and art critic for the New Statesman.