In Focus: The magnificent de Morgans, one of art's great husband-and-wife duos

Evelyn and William de Morgan were a husband and wife who were among the most inventive artists of their generation. Caroline Bugler takes a look at their mesmerising work, accompanies by pictures courtesy of the De Morgan Foundation.

It was an artistic fancy dress party in August 1883. Evelyn Pickering was dressed as a tube of rose-madder paint and William de Morgan declared that he was ‘madder still’. The chance meeting marked the beginning of a partnership between two of the most illustrious and eccentric figures of the Arts-and-Crafts Movement, who were loved and respected by their wide circle of artistic friends.

The de Morgans — ‘rare souls’, as Evelyn’s teacher Sir Edward Poynter called them — were already established in their own careers when their paths crossed that day. They worked quite independently and in different mediums, although they shared passionate beliefs in pacifism, social reform, voting rights for women and spiritualism.

William (1839–1917) abandoned his early ambitions to be ‘a real artist’ after meeting William Morris, and turned his hand to making stained glass and furniture and decorating tiles for Morris’s company.

His appealing designs of leaves and flowers, often with a faintly medieval flavour, complemented Morris’s own wallpapers and fabrics, but it was an accidental discovery that led to his most distinctive creation. After finding that a shiny film of silver was produced on the surface of glass coated with silver nitrate if it was deprived of oxygen in the kiln, he began to experiment with producing lustre glazes for ceramics, managing to blow up his kiln in the process.

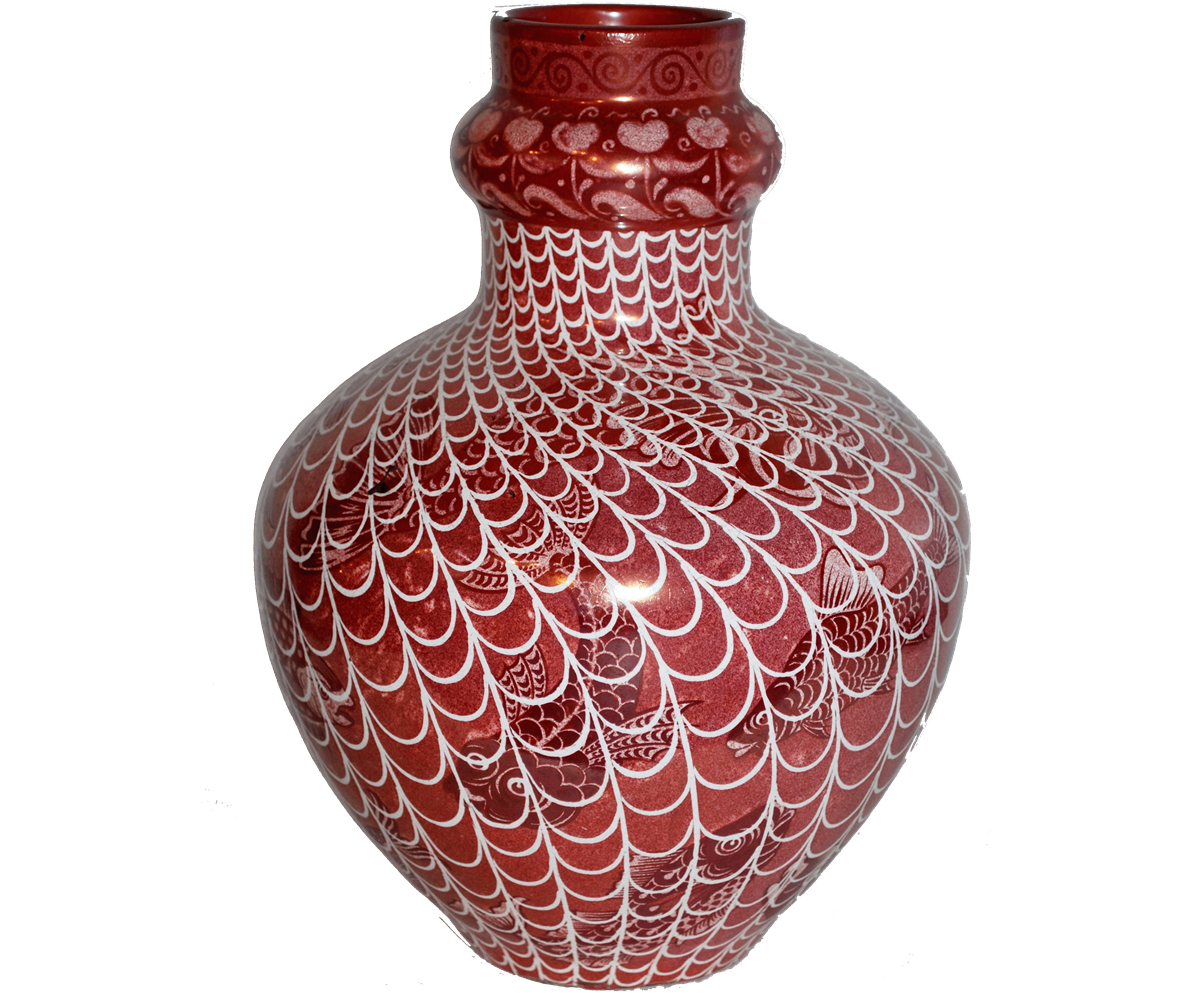

First produced in 9th-century Egypt, lustreware had been popular in the Renaissance, but had later fallen out of fashion. William set about reviving it, covering chargers, vases and plates with glowing iridescent gold and ruby glazes. Many of them feature flowers, plants, birds, fruit and fantastical beasts, such as dragons or mermaids, but one of the most striking examples is a vase with a fishnet pattern revealing tiny marine creatures caught in its mesh.

Other ceramics are decorated in brilliant cobalt blues and turquoises that are reminiscent of the fabulous Iznik, Persian and Syrian tiles that de Morgan helped to install in Lord Leighton’s famous Arab hall at his home in Kensington. That was not the only prestigious commission he received: he produced elaborate tile panels for the public rooms of 12 P&O passenger liners.

De Morgan ceramics are wildly popular today, but they gradually fell out of favour in William’s own lifetime and declining sales led him to wind up his business in 1907. Ever the innovator, he reinvented himself as a popular novelist, earning far more as a writer than as a ceramic artist.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

His literary efforts even strayed into supernatural realms. One extraordinary book he created with his wife, The Result of an Experiment, records automatic writing they believed contained messages from the spirit world. It may sound eccentric, but the de Morgans were by no means the only people in late-19th-century Britain who believed that the deceased and angels were longing to communicate with the living. Table tapping and séances were all the rage, especially among the liberally and artistically inclined.

An obsession with the unconscious, death and the afterlife finds its way into Evelyn’s paintings, too. In Memoriam shows a young woman mourning the loss of her loved one — the sun’s rays on the horizon nonetheless introducing a note of hope. In the remarkable Night and Sleep, two airborne figures float above the landscape scattering poppies of oblivion. These pictures reveal her incredible mastery of anatomy and figure drawing.

It’s obvious that Evelyn (1855–1919) was taught well. She was one of the first women to get a proper art education at the Slade School of Art, but it took determination to get there. Her mother wanted ‘a daughter not an artist’ — a girl who would do the rounds of coming-out balls and bag a rich husband. Little wonder that some of her paintings show women trapped or imprisoned.

Her distinctive style — a mixture of the Classicism taught at the Slade, late Pre-Raphaelitism and the work of Botticelli, which she saw on her frequent trips to Florence — earned her commercial success.

For a while, sales of her work propped up William’s ceramics company. After his novels began to generate an income, she was free to produce paintings that promoted her pacifist and spiritualist agendas in a more overt way. Official War Artists portrayed the horrific realities of the First World War, but Evelyn preferred to focus on the spiritual.

In the gaudy and newly conserved Our Lady of Peace — an expression of her hope for peace after the Boer War — the Virgin Mary stands in a rainbow-coloured stream, surrounded by cherub heads and worshipped by a knight in armour. As is a number of her paintings it is vaguely reminiscent of 1970s psychedelia; what modern viewers will probably find more appealing are preparatory drawings, showing just what a skilled draughtswoman she was.

| The De Morgan FoundationFor more than half a century, the De Morgan Foundation has kept the artists’ memory alive, caring for more than 3,000 examples of their work and sharing them with museums and galleries around the UK. The collection was formed by Evelyn’s sister, Mrs Wilhelmina Stirling (1865–1965), who was indefatigable in her efforts to promote their legacy. The Foundation currently has no permanent display place of its own, but several pieces are on long-term loan to museums and galleries throughout the UK, including the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; The Queen’s House, Greenwich; Standen House, East Grinstead, West Sussex; Jackfield Tile Museum, Ironbridge, Shropshire; and Buckler’s Hard Maritime Museum, Beaulieu, Hampshire. The De Morgan Foundation website gives further information about the two artists and updates on temporary exhibitions (www.demorgan.org.uk). The Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle’s exhibition ‘William and Evelyn de Morgan: Two of the Rarest Spirits of the Age’ is closed at the moment due to the lockdown, but the gallery currently plans to reopen on May 1 and the exhibition will continue until June 20. ‘Sublime Symmetry: The Mathematics behind De Morgan’s Ceramic Designs’ will be on show at the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, Wirral, from October. |

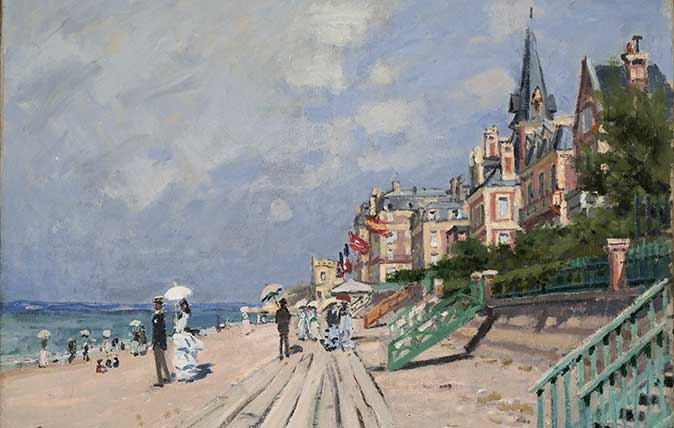

In Focus: The paintings which show Monet's genius for architecture as well as nature

Think of Monet and you think of reflections and nature, but his works included huge amounts of architecture and other

The eloquence of line: Raphael’s drawings at the Ashmolean Museum

Caroline Bugler admires the beauty and expressive power of Raphael’s drawings.

Credit: Photopia Photography / Edward Bulmer

How to decorate your entrance hall: Choosing colours, right lighting and what to do about furniture and pictures

Architectural historian, interior designer and natural-paint specialist Edward Bulmer reveals the secrets of successful hallway decorating.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.