In Focus: Thomas Geve, the boy who drew Auschwitz

After being liberated from a Nazi death camp, a Jewish boy sketched more than 80 profoundly moving drawings detailing his incarceration. Charlie Inglefield explains how he came to co-author a book of Thomas Geve’s powerful words and pictures.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Today, Zug — the small, Swiss lakeside town where I live — is home to some of the world’s largest companies, but, in 1945, it was a humble farming community renowned for its cherry production. That summer, the Felsenegg children’s home poised on top of the Zugerberg, a mountain overlooking the town, opened its doors to 107 exhausted and bewildered boys and girls, who had arrived from the horrors of Buchenwald concentration camp in Weimar, Germany.

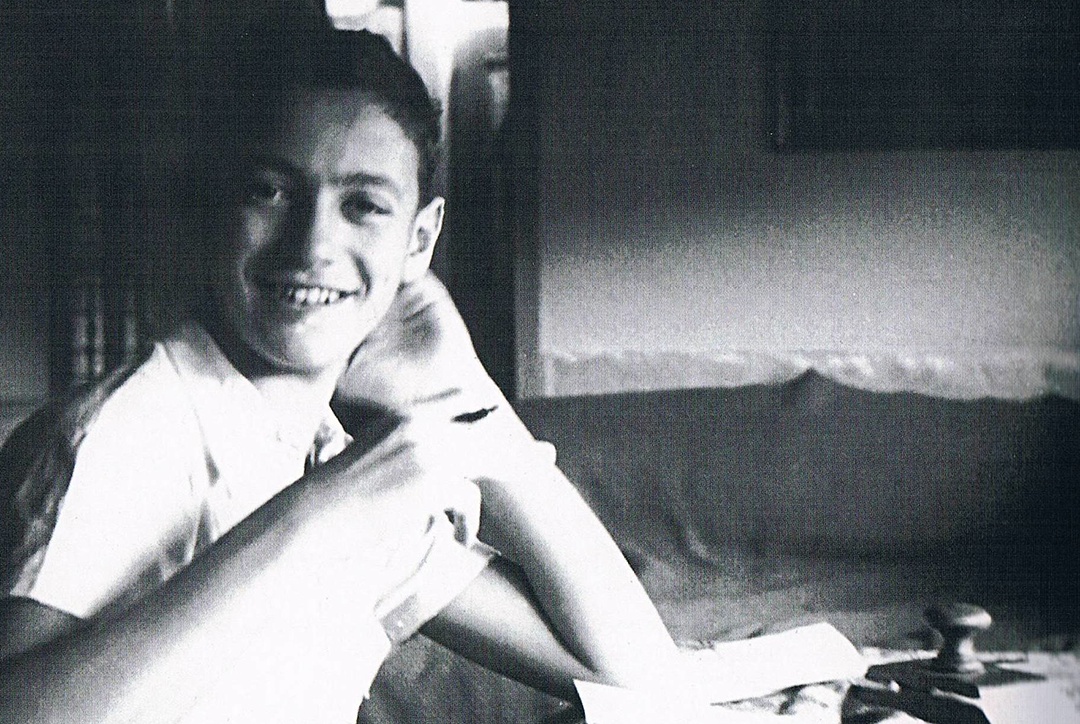

A 15-year-old Jewish boy called Thomas Geve (his pseudonym) was among them.

I came across Thomas’s story by chance, thanks to a client of mine, Natalie Albrecht, who told me about an exhibition at Zug’s Burg Museum and gave me a leaflet entitled The Children of Buchenwald. I’ve always been interested in Second World War history and was intrigued by Switzerland’s role. The leaflet explained how the Swiss alpine scenery allowed the children a chance to start their recovery and why for many, such as Thomas — who was mentioned by name — drawing and writing about their experiences was a great help, too.

After researching a little further, I found Thomas’s powerful drawings of his time in no fewer than three Nazi concentration camps and, after contacting his daughter, Yifat, arranged to meet him in Israel in July 2019.

A ‘German’ Jew, Thomas and his mother were forced to move from Beuthen to Berlin as Hitler’s brutal persecution gathered pace in 1939 and 1940. A streetwise child, Thomas was never interested in school or teachers, instead believing in what he could see in front of him and the wonders of technology — not least because, at that time, Berlin was glistening with Nazi invention and industrial progression. In the years to come, those beliefs were to save his life.

Evading the SS, the Gestapo and the many informers on Berlin’s streets, Thomas and his mother survived for more than two years before handing themselves in, in June 1943. With no money and barely any food, they had little choice.

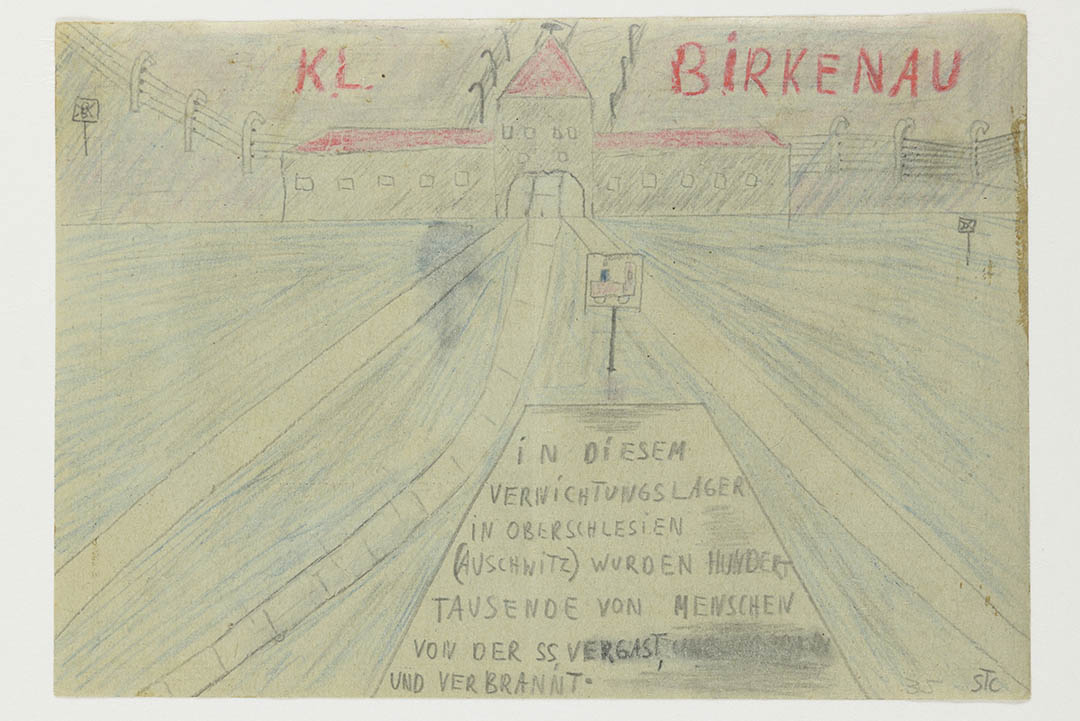

At the time, rumours were circulating that Germany’s Jewry could settle in the east and earn money by working hard. Sent on transport 39 — one of the last to leave Berlin — they arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau on June 29, 1943. Their hopes of a better existence were crushed as they stepped out of the wagons and on to the platform.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Nearly two years later, at the age of 15 — having survived Auschwitz-Birkenau (where he was separated from his mother, who, tragically, did not), Gross-Rosen and Buchenwald — Thomas was liberated on April 11, 1945.

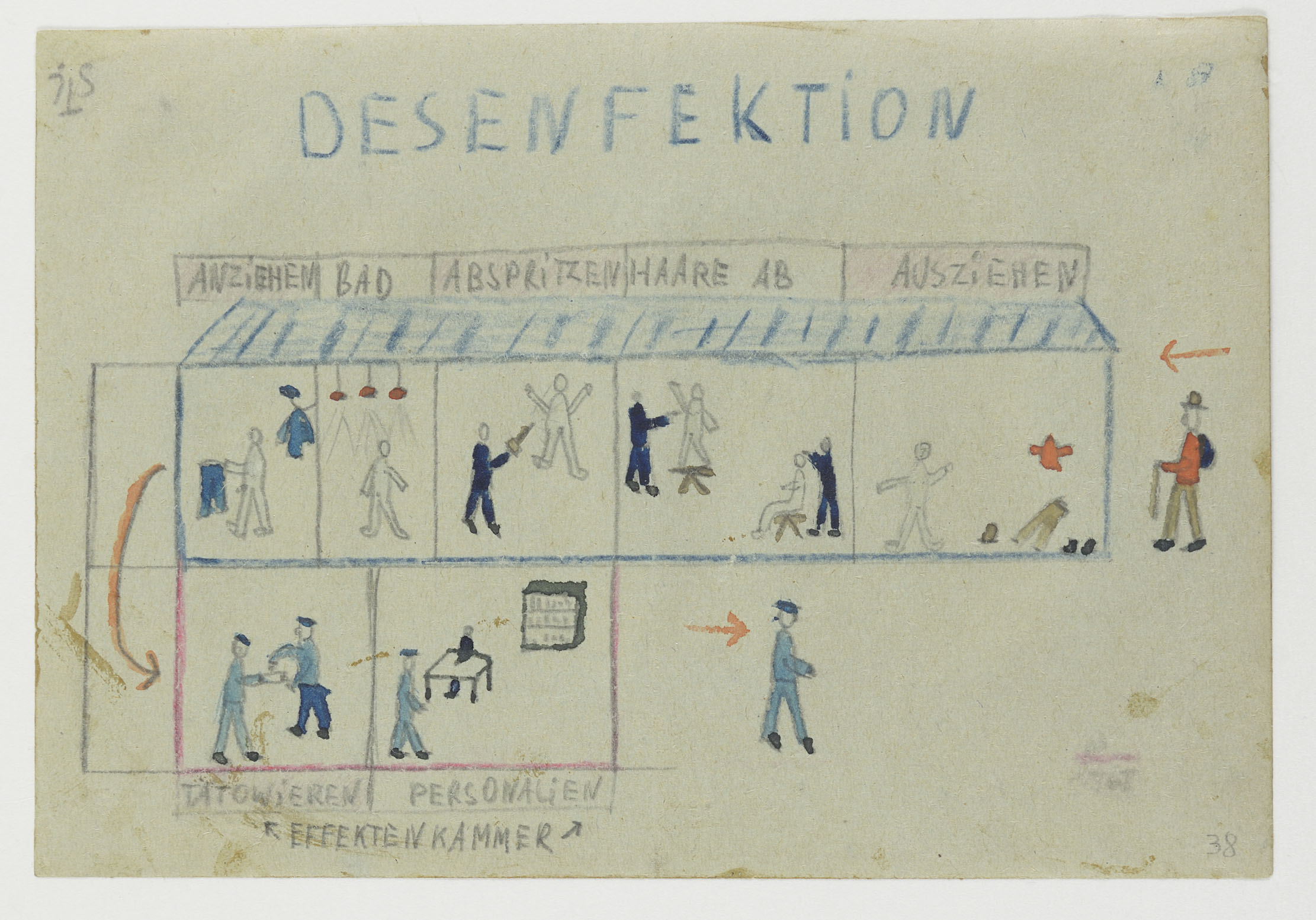

In the days following his release, Thomas obtained some discarded SS ration cards and colour pencils, then proceeded to sketch more than 80 drawings, which, over the past 76 years, have become an important record of life in concentration camps. ‘If we told people what we went through, they would not believe us. So, I decided to draw my experiences of life in the camps,’ he explained.

I have been so fortunate to work with Thomas to co-author his updated testimony in a new book, The Boy Who Drew Auschwitz, which follows his first two books, Youth in Chains and Guns & Barbed Wire, published in 1958 and 1987 respectively. Our aim with this latest edition was to make Thomas’s story more digestible and easier to navigate for today’s readers.

As a first-time author writing about such a sensitive subject, it was a huge challenge to take on, not least because the Covid-19 pandemic robbed us of the opportunity to continue to work together in person. Never-theless, Yifat did an amazing job of liaising between us and helping us to communicate.

Looking back, I was so lucky to have had that initial week with Thomas in Israel, back in 2019. Understandably, he isn’t a man of many words, but what he did reveal was moving and insightful. I particularly remember sharing a taxi to Jerusalem, en route to a talk he was giving at the Yad Vashem Museum, when we spoke about his childhood in Berlin and I asked how he felt he had been able to survive the concentration camps.

‘I didn’t like textbooks or school. I was a boy of the streets — I wanted to explore. I did not spend my time reading in the synagogues like a lot of Jewish children,’ he replied.

‘I concentrated on doing what I was told and putting one foot in front of the other.’

Throughout our interviews, it became clear that, even as a child, Thomas possessed great maturity and strength of character — he was tall for his age, able to make people laugh, remember songs and quickly pick up snippets of different languages. These characteristics would prove to be the difference between living or dying, enabling him to scrounge an additional bowl of soup or a mouldy piece of bread.

In this book, Thomas does not ignore the horror of the Holocaust; however, he prefers to concentrate on positivity, hope and survival — how his friends and fellow inmates lived and survived the camps.

Now 91, Thomas’s attention to detail — as befitting his career as an engineer — is as sharp as ever, with a clear recollection of his childhood honed by years of giving testimonies in Israel and around Europe. He has always stuck to the precise details of what he saw and went through and I felt privileged to have spent time with Thomas and to have the chance to help him retell his story.

I came back to Switzerland determined to fulfil his wish of reaching future generations and set about writing a book proposal. Happily, HarperCollins believed in the story straightaway, although it took me a while to adapt to my role as a co-author, interviewer, listener, student and editor.

I made mistakes, but kept learning. At first, I found Thomas’s descriptions difficult to understand, but realised that his original language should not be altered unless absolutely necessary. We can never fully comprehend what he endured and, therefore, changing his words would detract from what he felt and experienced.

Thomas’s aim has never changed during the past 76 years — he’s always wanted to share exactly what he saw in those Nazi concentration camps. By documenting his story, we can all learn about this horrific period of world history and ensure it never happens again.

It is very rare to be able to bring the words and drawings of a living Holocaust survivor together in this way. If a picture is worth 1,000 words, Thomas has achieved that and so much more.

‘The Boy Who Drew Auschwitz: A Powerful True Story of Hope and Survival’, by Thomas Geve and Charlie Inglefield, is out now (HarperCollins, £18.99)

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.