‘The perfect hostess, he called her’: A five minute guide to Virgina Woolf’s ‘Mrs Dalloway’

To mark its centenary, Lotte Brundle delves into the lauded writer’s strange and poignant classic, set across a single summer’s day in 1920’s London.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Mrs Dalloway is shallow, unlikable and obsessed with a man she turned down many years ago and a woman she could never have. I remember not understanding the complexities of her sexuality, class criticisms and muddled inner monologue when I first read the novel that takes her name at school. The way Virginia Woolf played with language and reality with such deft skill eluded me, preoccupied (as I obviously was, at an all girls’ school while studying the Feminist Literature module) with the titular character’s phallic obsession with Peter Walsh’s penknife.

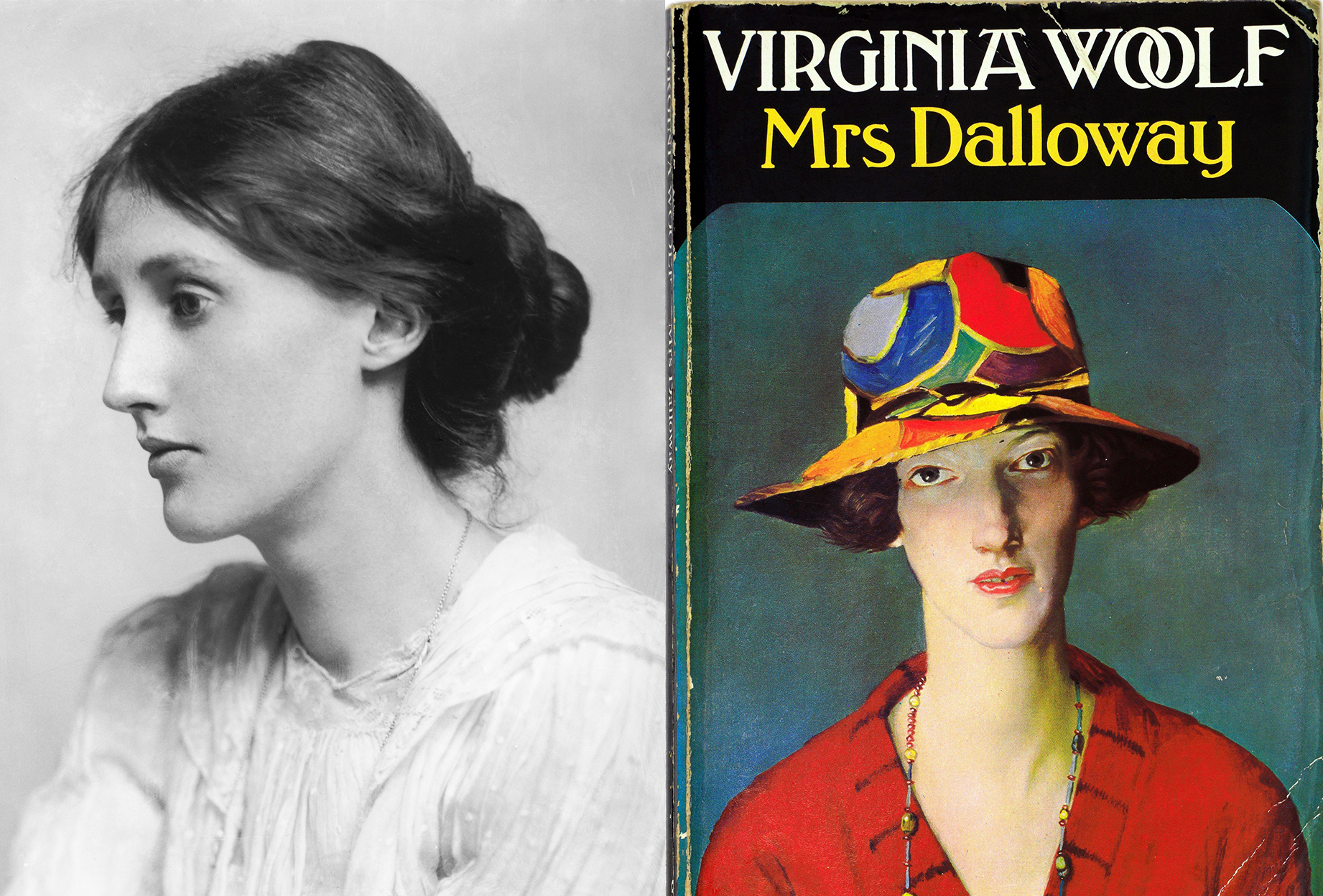

Virginia Woolf was born in 1882 in South Kensington; Mrs Dalloway was published when she was 43 years old.

Alas, Woolf’s literary masterpiece was wasted on me in my youth. Returning to it now, however, almost ten years after I first turned its pages, and 100 years after it was first published, I am able to see parts of Dalloway I couldn’t before. It is a book that has the continuing ability to surprise anew. And so, for the uninitiated, let me provide a short introduction.

Woolf was born in 1882 in South Kensington. Part of the Bloomsbury set, the Modernist author helped pioneer the literary device stream of consciousness, letting readers observe the slow and often winding progress of her character's thoughts. She was affluent and educated, though she did not attend university until many years after her male counterparts. She is best known for To The Lighthouse (1927), Orlando (1928) and A Room of One’s Own (1929). Her campaigning for women’s rights and affair with Vita Sackville-West, despite both of their marriages, may have been what she was remembered for, where they not eclipsed by her mental health struggles and ultimate suicide.

Vanessa Redgrave played Clarissa Dalloway in the 1997 film adaptation of Woolf's novel.

Mrs Dalloway is one of the most impressive of her works. The book charts a typical day in London and the inner workings of the people that live there. It hovers in particular on socialite and politician's wife Clarissa Dalloway as she prepares to host a party. In tandem, it charts First World War veteran Septumus Warren Smith’s struggles with PTSD and his tragic death. These narratives intertwine, without the pair ever actually meeting.

'None but the mentally fit should aspire to read this novel'

The Scotsman on 'Mrs Dalloway'

The book was written in the aftermath of the War, when society was grappling with how to live now that the conflict was over. This is reflected in Woolf’s use of stream of consciousness, and her character’s preoccupation with their own mortality, not helped by the omnipresent hourly chimes of Big Ben. It is mired in introspection and feelings of bewilderment and subverts many of the norms of traditional novel writing that had come before. For this reason, it is frequently accepted to be a response to James Joyce’s maddeningly untraversable Ulysses, although Woolf denied this and called Joyce’s seminal work ‘pretentious’ and ‘very obscure’ and Joyce, ‘egotistic’ and ‘ultimately nauseating’. Considering that I had Joyce's monstrosity of a novel foisted on me at university, I wholeheartedly agree.

Virginia Woolf with her Cocker Spaniel, Pinka, at her feet, taken in London in 1939.

Mrs Dalloway was, for the most part, well-received at the time of publication, although some deemed it too experimental, with its lack of traditional chapters a bridge too far. The Western Mail were particularly upset. ‘This novel is in one chapter, 283 pages of it,’ their reviewer wrote. ‘That is a normal length, but we like to have places which we can dog-ear when we go to bed, with the certainty of restarting at the exact line.’ The Scotsman advised ‘none but the mentally fit should aspire to read this novel’, The Sketch simply stated a fact by way of criticism: ‘The author of this book is Virginia Woolf, and it is published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press, Tavistock Square.’

The Times Literary Supplement, however, was all praise: ‘People and events here have a peculiar, almost ethereal transparency, as though bathed in a medium where one thing permeates another,’ their reviewer wrote. ‘Undoubtedly our world is less solid than it was, and our novels may have to shake themselves a little free of matter.’ Despite its contemporary critics, and the lack of respect it received in my school English class, it became, and remains one of the most influential works of literature, not only in the feminist cannon, but of all time. Well worth a first read, or re-read, in its centenary year, at any rate.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Lotte is Country Life's Digital Writer. Before joining in 2025, she was checking commas and writing news headlines for The Times and The Sunday Times as a sub-editor. She has written for The Times, New Statesman, The Fence and Dispatch magazine. She pens Country Life Online's arts and culture interview series, Consuming Passions.