From James Bond to Centre Court, how terry towelling took the world by comfort

Terry towelling — whether it be clothing babies, adorning a poolside Bond or mopping tennis players’ brows — altered domestic life forever.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The letter from St James’s Palace was written on April 15, 1851, at the command of the Mistress of the Robes. It requested ‘six Dozens’ of ‘the Royal Turkish Towel’ to be sent, care of Queen Victoria’s dresser Miss Skerrett, to Buckingham Palace ‘for the Service of Her Majesty’.

The ‘Turkish’ towels in question were, in fact, manufactured in the small Lancashire mill town of Droylsden, on the Ashton canal east of Manchester, woven on a mechanised loom newly invented by a former child labourer, Samuel Holt. Within a fortnight of receipt of the Queen’s order, examples of Holt’s towels — woven with a pile of loops of uncut thread able to absorb quantities of water — went on display in the Great Exhibition. The usefulness of Holt’s innovation, alongside the Queen’s endorsement via her agreement to the inclusion of the adjective ‘Royal’ in the towels’ name, ensured that popularity followed swiftly.

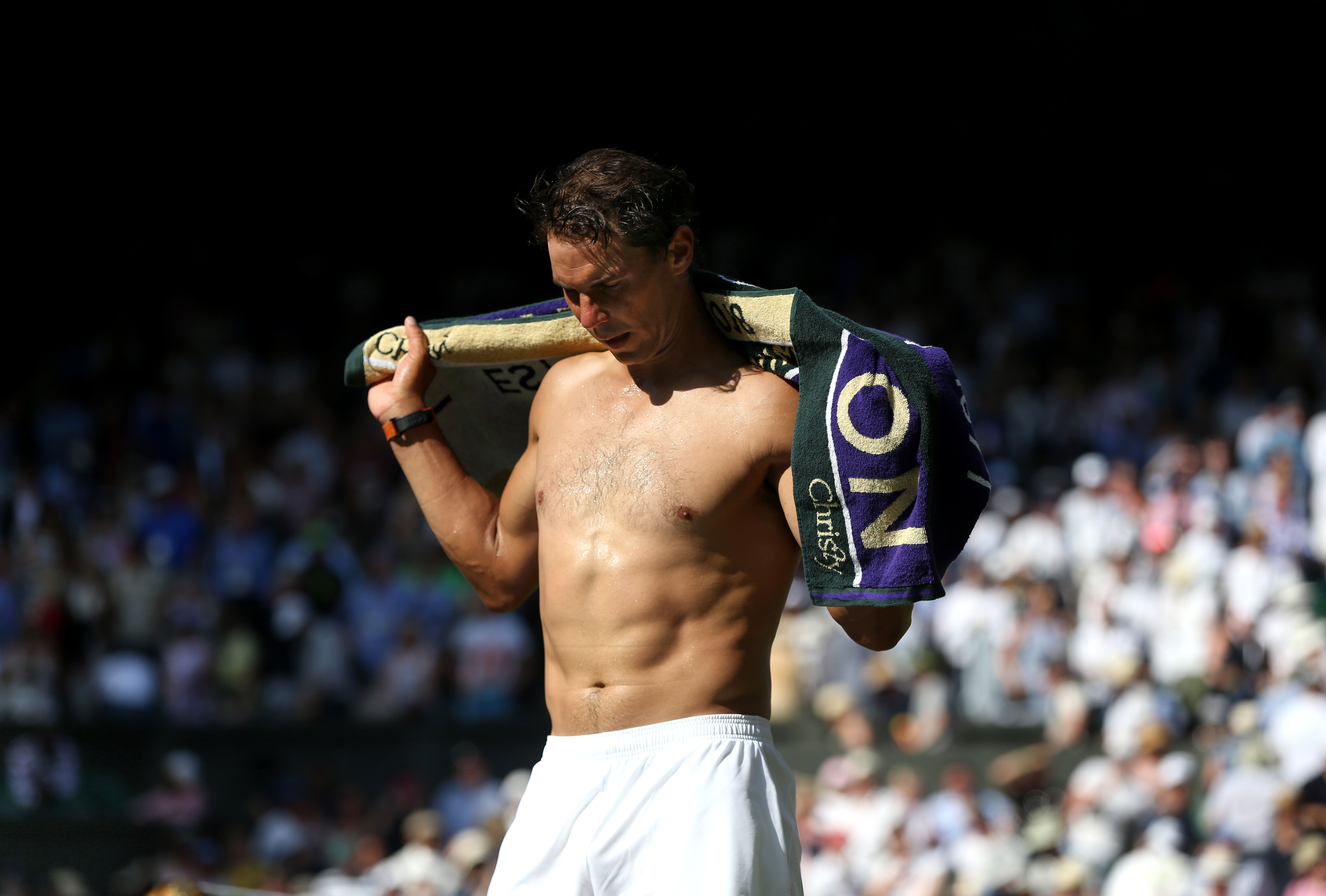

The Times reported in 2013 that only a third of the towels Christy supplies to the Championship are returned, due to the players keeping them or throwing them into the crowd as mementos.

In origin, what has come to be called terry towelling (the name possibly a corruption of the French adjective tire, meaning ‘pulled’, referring to the fabric’s uncut warp threads, which account for its absorbent qualities) was neither a British nor a Victorian invention. Holt developed his loom in response to a request from his employer Richard Christy. He, in turn, had been inspired by the traveller’s tales of his elder brother, Henry.

On his death in 1865, The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Review described Henry Christy as a man who had undertaken ‘extensive voyages for the purpose of studying the antiquarian remains of various districts and the primitive customs of the more remote tribes of men’. A keen amateur botanist as a young man, Christy — the eldest surviving son of the 10 children of a Quaker hatmaker — had become passionately interested in ethnography and archaeology. Despite his membership of the Aborigines’ Protection Society and several overseas trips motivated by a desire to ‘observe… such tribes before the influence of European civilisation has obliterated their distinctive characteristics’, his chief focus was the early cultures of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East — later, he bequeathed his collection of Cypriot antiquities to the British Museum. It was in Ottoman Turkey that he encountered, for the first time, an age-old fabric that would transform the ablutions of his countrymen into the next century and beyond.

In the harem of Abdul-Mejid I in Constantinople, Christy witnessed the Sultan’s concubines handweaving towels. He obtained a sample of the woven fabric, which he brought back to the mills founded by his father in the 1830s. Holt produced his first towelling loom in 1848 and, shortly afterwards, refined the process further. His employers patented his invention. Towel production began in 1850 and, in the following decade, W. M. Christy & Co bought Holt’s patents from him, offering him in return an annuity of £30. Among the first terry-towelling towels the company produced were those that resembled their Turkish forerunners, with fringed or knotted edges.

Ian Fleming's ‘dark blue tropical worsted suit’ was substituted for something a little more flamboyant.

Almost two centuries after W. M. Christy & Co introduced terry towelling to the British public, this hardwearing and practical fabric has been put to a range of uses. Christy promoted it as ‘soft, absorbent, durable’, ideal qualities for babies’ nappies. Garments for water wear were also made from quick-to-dry terry towelling. In 1928, Christy’s produced cape-like, collared bathing wraps for ‘the Holiday Season’; terry-towelling bathing suits would follow and 1960s towelling poolside kaftans made by Pucci are now collectors’ items.

The fabric’s benefits were shared with men, too, including sartorial arbiter elegantiarum and fictional government agent James Bond. In the 1964 Goldfinger film, in place of the ‘dark blue tropical worsted suit’ stipulated by Ian Fleming, Sean Connery’s Bond wears a terry-towelling romper suit. The belted, zip-fastening all-in-one garment is a practical coverup for Connery’s bathing trunks. Bond wore terry towelling again in Diamonds are Forever, the following decade, in the form of a short-sleeved shirt.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

'Every gym bunny has reason to give thanks for a fabric with a history stretching back millennia to North Africa'

The recommendations of terry towelling for hot-weather clothing include not only its lightness, but its sweat absorbency. The fabric has repeatedly been used in sports clothing — and not only water sports. Wristbands and headbands of terry towelling were once ubiquitous on squash and tennis courts; in 1983, the film Flashdance began a craze for towelling head-bands. Jogging pants, hoodies and tracksuits continue to be made from terry towelling and towelling variants; fashion brand Orla Keily designed terry-towelling sun hats.

Today, disposable nappies have banished the fabric equivalents from the majority of nurseries and Bond romper suits are a rarity, but every parent who scoops a shivering child from the sea, every gym bunny emerging from the showers, everyone whose bath relaxes them has reason to give thanks for a fabric with a history stretching back millennia to North Africa and which altered domestic life in Industrial Revolution Britain forever.

This feature originally appeared in the July 30, 2025, issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe