Kermit the frog, a silver-horned goat and Charles III’s 69ft-long coronation record star in a groundbreaking exhibition

‘Happy & Glorious’, at the The National Archives in Kew, captures the spirit of the King’s coronation with works by eight contemporary artists alongside the official roll of the day — and that of Edward II’s crowning in 1308.

Kermit the frog claps his hands in glee, eyes dancing, a big smile plastered on his face. He, Fozzie Bear, Rowlf the Dog and a bunch of other muppets are clustered around an old-fashioned television, watching Charles III being crowned. They are not, however, appearing on a screen themselves. They are figures in a painting by Leslie Thompson, one of eight artists commissioned by the Government Art Collection to capture the spirit of the King and Queen’s Coronation on May 6, 2023. Their works are now on show at the Happy & Glorious exhibition at The National Archives in Kew (until November 2).

Thompson’s pop-art inspired vignettes — displayed alongside his large Crowd of People and the Different People, an ink on board ‘map’ of people past, present and fantastical all watching Charles III being crowned — also include the animals of the London Zoo watching the ceremony and Mum, a touching tribute to the artist’s late mother, who sits on her favourite armchair, cup of tea on hand, and smiles as the King and Queen wave at the crowd from her TV set.

Vignettes of a very different kind, not only in medium (photography, this time), but also in atmosphere, appear in the work of Vanley Burghe. Based in Birmingham, he has long been documenting the lives of the city’s working-class communities, particularly those of Afro-Caribbean origin and in this commission he set out to capture what the ceremony meant to people who had been deeply hurt by the Windrush scandal.

He points at Mrs Belgrave-Maghee on a throne, a picture of an elderly woman ensconced on a suitably royal seat (above). ‘There’s a group of young kids who visit an art club — they made a throne. Quite importantly, if you look at the stool she's resting her feet on, it is broken and it's the whole idea about the local community and how they feel they've been over the years. It’s an emblem.’ Just as poignant is another picture he took, of a Sikh woman wearing a traditional outfit against a Union Jack. She captures the essence of today’s Britain — yet her gaze is as troubled as it is beautiful.

Photography is the medium of choice for three of the eight exhibition commissions, but the artists each put their own spin on it, whether it’s little children dressed up in ‘royal’ attire, as in the pictures taken by Sophie Gerrard in villages near Balmoral, in Scotland, or in Mohammed Hassan’s views of Welsh reactions to the Coronation: a daffodil-bearing lady of Chinese origins swathed in traditional Welsh clothing; a delightfully zany goat with silver-clad horns; or the unruffled stillness of the Brecon Beacons, a powerful reminder that even royal ceremonies pale to insignificance against the glory of Nature.

‘We were very keen that we had artists right across the UK, Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales — that was a key criterion [for the commissions],’ says Government Art Collection curator Theo Weiss. ‘The other one was to work with artists, some of whom we were familiar with and some of whom were completely new to us, but whose work excited us, and we thought would have interesting things to say about Coronation, providing a range of emotional responses.’

Where photography showed the moods of the country, the conceptual work of Cornelia Parker explored the many definitions of king and queen in an embroidered diptych hand-sewn on both front and back — a reminder, in the artist’s words, that ‘every facet of life has an underside’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Textiles also appear in Hew Locke’s extraordinary Flag, a multimedia triumph of red and gold, velvet and linen, acrylic paint and brass, in which echoes of the Windrush return. Layered images transform the Gold State Coach into a Ship of State sailing into unknown waters and carrying Caribbean cane cutters — the ancestors of those that would arrive in Britain in 1948.

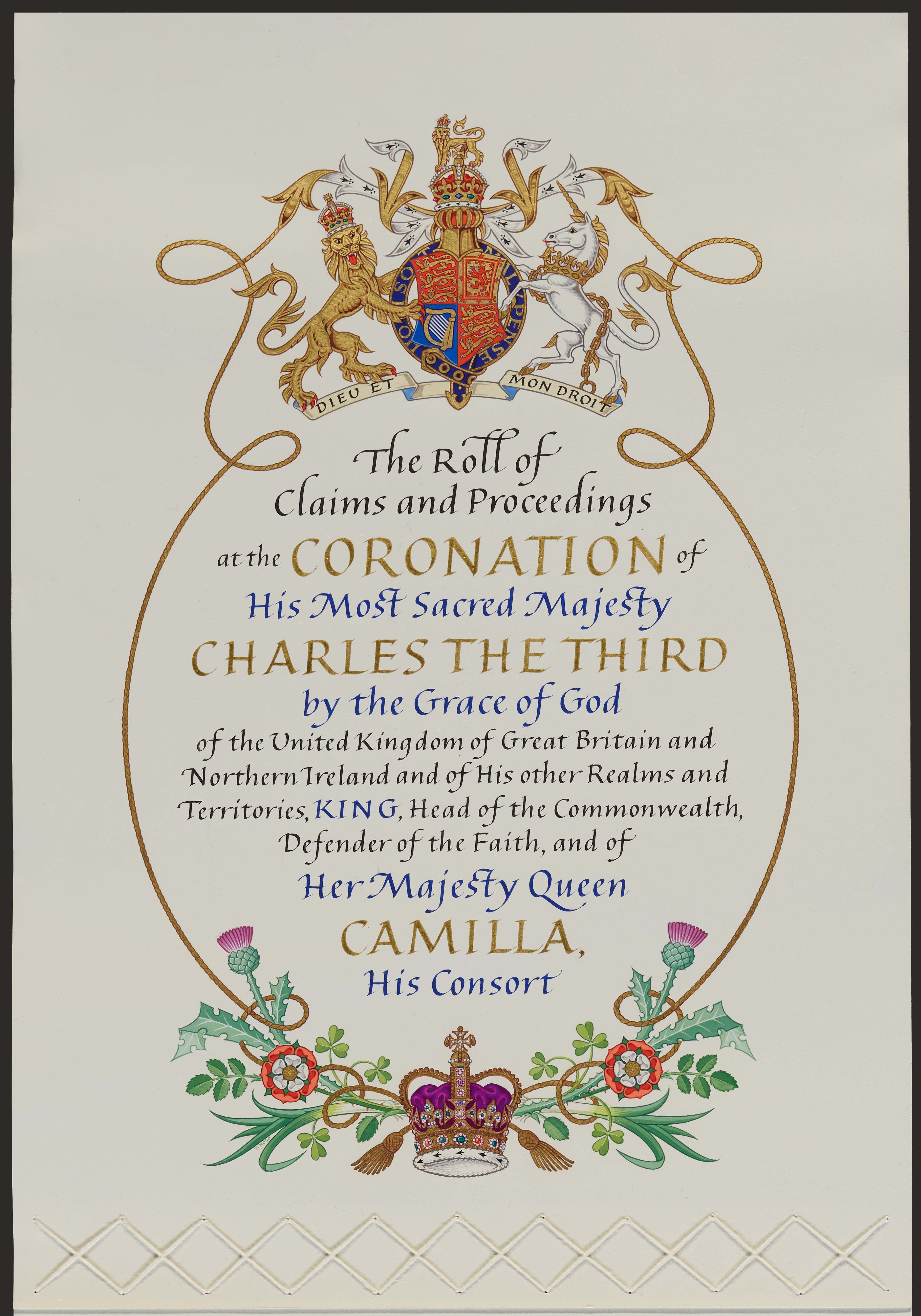

The centrepiece of the show, however, is an artwork of a different kind: the coronation roll of Charles III and Queen Camilla, 21 metres (nearly 69 feet) of paper — which the King, breaking with tradition, expressly chose over parchment for environmental reasons — decorated by artist Tim Noad and heroically hand written by calligrapher Stephanie Gill (left).

‘The good thing was all written in separate sheets, so she could have corrected a sheet [rather than re-do the whole thing],’ says Sean Cunningham, The head of medieval collections at The National Archives. ‘It was still being adjusted on the morning we actually had it signed off by the clerk of the Crown to say: “this document is now a complete record of the ceremony.”’

Rolls provide the legal documentation for each coronation, detailing everything from the proclamation of the new king or queen to the oaths, the list of people attending the service in order of rank and a narrative account of the ceremony. Although much of what appears on the document is prescribed, Charles III had his say: ‘He had his input into the colors, the way that this interpretation of the British symbols would be put together. The Royal crest is a very formal sort of heraldry, but this is a little bit more stylised.’

Elizabeth II’s coronation was filmed so it could be shown across the Commonwealth, but the current roll is the first to have a digital version that includes footage of the events, so people can actually see what it is describing. It will be an extraordinary resource for future historians, just as the other roll now displayed alongside it at The National Archives has proved to be in the past.

The earliest of the 18 that survive, it details, in Latin with exquisite red and blue lettering, the 1308 coronation of Edward II and Queen Isabella — and has long been an invaluable record not only for historians, but for monarchs, too. James II, desperate for information on how to ‘do’ a Coronation, and, before him, Charles II, restored to the throne after the upheaval of the Commonwealth, both relied on the 1308 roll. The Cromwell years had not only wiped out much institutional knowledge, but also disposed of the Crown jewels and many of the objects used in the ceremony, ‘They had to be remade so,’ explains Cunningham, ‘that's why they used this [roll] as an archive. Charles II made an order to go back and look at the ancient texts, which would include the narrative stuff: which Duke got to carry the king slippers, who put the gloves on the king or the ring on his finger.’

The Coronation ceremony may have become slimmer and more streamlined since then, but in the new Carolean age the rolls remain to remind us all of the monarchy’s heritage and sense of continuity with the past.

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.