In Focus: The many lives of Landseer's 'The Monarch of the Glen', the eternal symbol of Scotland

The most famous of Victorian paintings took on a life of its own as a marketing icon, romantic symbol of Scottish identity and inspiration for numerous other artists in a way that could never have been imagined by – and might well have horrified – its creator, the outstanding animal painter Sir Edwin Landseer, says Christopher Baker.

After breakfast on the morning of April 8, 1851, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert left Buckingham Palace and visited a private house in St John’s Wood. It was the home and studio of the then world-famous artist Sir Edwin Landseer (1802–73) and the royal visitors had come to view the paintings he was to show at the Royal Academy (RA) that summer.

The Queen noted in her Journal seeing ‘a life size stag, sniffing the air, with mist rising from the mountains’ – a reference to what was to become not only Landseer’s best-known work, but also, perhaps, the most reproduced of all 19th-century British paintings.

Landseer, had never intended to exhibit and sell The Monarch of the Glen through the RA. This change of plan proved, however, to be the first of numerous twists and turns of fate that resulted in the transformation of the painting’s status from an aristocratic commission to a marketing image with a global reach and a source of inspiration for numerous other artists.

'He saw Scotland and its scenery and wildlife through the filter of Sir Walter Scott’s writings, as a land of beauty, romance and tragic history.'

By the time of the royal visit, Landseer was an immensely successful painter. Born in London to an artistic family, he had, from an early age, specialised in depicting animals, becoming renowned for the technical mastery, drama and endearing sentimentality of some of his most famous works. He had secured distinguished patronage from collectors, such as the Dukes of Bedford and Devonshire, as well as new metropolitan enthusiasts, and had the art world at his feet.

From the mid 1820s, annual visits to the Highlands provided profound inspiration for a number of Landseer’s most successful works: he saw Scotland and its scenery and wildlife through the filter of Sir Walter Scott’s writings, as a land of beauty, romance and tragic history. It was also an escape from the confines of city life, where he could stalk, fish and paint; Landseer was a popular guest at Highland shooting lodges.

In view of his unchallenged status as Britain’s pre-eminent animal painter, it was unsurprising that the Fine Arts Commission, which was responsible for sourcing works of art for the new Houses of Parliament in the 1840s, turned to him. Most of the paintings commissioned for this setting were of exemplary historical or allegorical subjects, but it was decided to soften this agenda in the parliamentary dining rooms.

The ‘refreshment room’ in the House of Lords was to feature depictions of ‘the chase’ and Landseer was commissioned to provide three of them. The Monarch was the only work for the series he completed. It was never hung in its intended setting and remained in his studio for the Queen to admire, because the House of Commons refused to endorse the growing expenditure on the projects promoted by the commission.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Sir Robert Peel made an eloquent defence of Landseer’s work, but it failed to persuade his fellow Members of Parliament.

'A fine engraving by his brother was the first of innumerable reproductions, which ranged from the accurate and respectful to the crude and comic.'

This may have been a cause of frustration to Landseer, but it didn’t present him with a commercial problem. His paintings were keenly sought by collectors and the Monarch was bought from the RA exhibition by Albert Denison, Lord Londesborough, a politician and diplomat.

From that moment, until 2017, when it was purchased by the National Galleries of Scotland, it passed through various hands, staying in private and corporate collections. It was at no point, however, invisible.

In 1852, a fine engraving after the painting was created by Landseer’s older brother Thomas. This was the first of innumerable reproductions, which ranged from the accurate and respectful to the crude and comic. During Landseer’s life, he controlled the quality of the prints after his works and the copyright payments he received provided a substantial income.

Later, however, such constraints fell away and the uses to which the image was put extended far beyond anything its creator could possibly have imagined – or indeed, it’s safe to assume, would have endorsed.

In 1884, the picture was acquired by another private collector, Henry William Eaton, Lord Cheylesmore, who had a taste both for contemporary art and monumental works of great drama; he also owned Paul Delaroche’s huge Execution of Lady Jane Grey, now in the National Gallery.

It was, however, the next owner of the painting whose commercial instincts led to its wider exploitation. Thomas James Barratt (1841–1914) was a pioneer of the advertising industry and chairman of soap manufacturer Pears. He invested heavily in advertisements and recognised the benefit of celebrity endorsements for products. The ‘celebrities’ he used could be actual people, such as Lillie Langtry, or renowned works of art.

The painting he most effectively employed in this way was Sir John Everett Millais’s Bubbles, which depicted the artist’s grandson in a manner that refers to the traditional idea that human life is as transient and insubstantial as a bubble. Rather than dwelling on such philosophising, Barratt saw the benefit of aligning the charm of the painted bubbles with soap – or art with advertising.

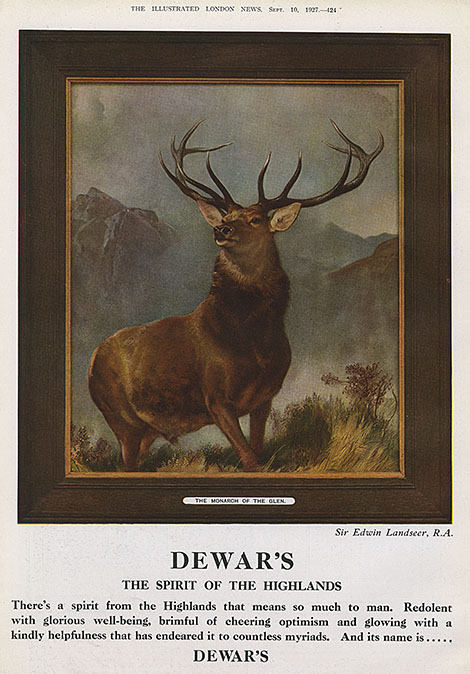

Barratt’s hugely successful commercial move inspired Thomas Dewar, 1st Baron Dewar (1864–1930). In 1916, he bought the Monarch to help promote an archetypal Scottish product: the whisky he successfully distilled. The painting’s status as a Scottish icon had been growing through its appearance in exhibitions and the sale of engravings; now, the image became a global export and an unapologetically commercial asset.

In the wake of this canny association of Landseer’s Monarch with whisky, the painting was reproduced on innumerable other products and souvenirs – and, indeed, continues to be. Shortbread and soup are perhaps the most famous, but there seems to be no end to its recycling. It has featured on tea towels and ashtrays, cough cures, packs of butter and even cheques issued by American banks.

'It became so lodged in the public consciousness that it could be used to work for many different agendas – political, literary and artistic.'

This all kept the painting remarkably visible through the 20th century, when, conversely, the reputation of mid-Victorian art was in a steady decline. In fact, it became so lodged in the public consciousness that it could be used to work for many different agendas – political, literary and artistic.

These transformations first appear in 1914, when the brilliant cartoonist Bernard Partridge utilised the painting. His ‘The Monarch of the Glen’: A New Landseer depicts the Prime Minister Lloyd George riding on the stag and uses Landseer’s name in a punning way to refer to attempts to increase taxes on the value of land and redistribute wealth.

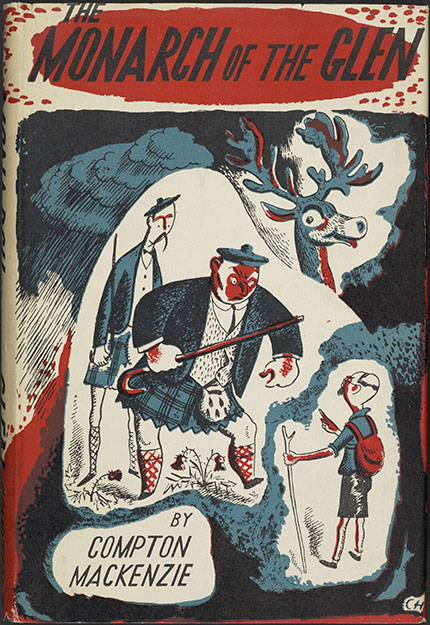

It was later, during the Second World War, that the title of the painting, rather than the artist’s name, was appropriated for literary purposes, when, in 1941, Compton Mackenzie published his witty novel The Monarch of the Glen. It was much admired, but became far more widely known in 2000 thanks to the BBC TV series that was inspired by it – a highly successful, gentle farce that plotted the romance and chaos of life in fictional Glenbogle.

Artistic responses to the painting itself have played cleverly on its dual status as a Victorian paragon in a later age of disrespect. In the mid 1950s, Ronald Searle, perhaps remembered above all as the creator of the anarchic St Trinian’s, illustrated an article in Punch, in which he reimagined illustrious works from the past as Picasso might have depicted them.

Here, Landseer’s stag becomes an agonised creature, a pastiche of the Modernism that had pushed the taste for 19th-century art to the periphery.

Landseer’s work continued to appear in advertisements and on products, and this ubiquity gave the Monarch a slightly ridiculous, archaic and kitsch quality, which, in turn, inspired affection.

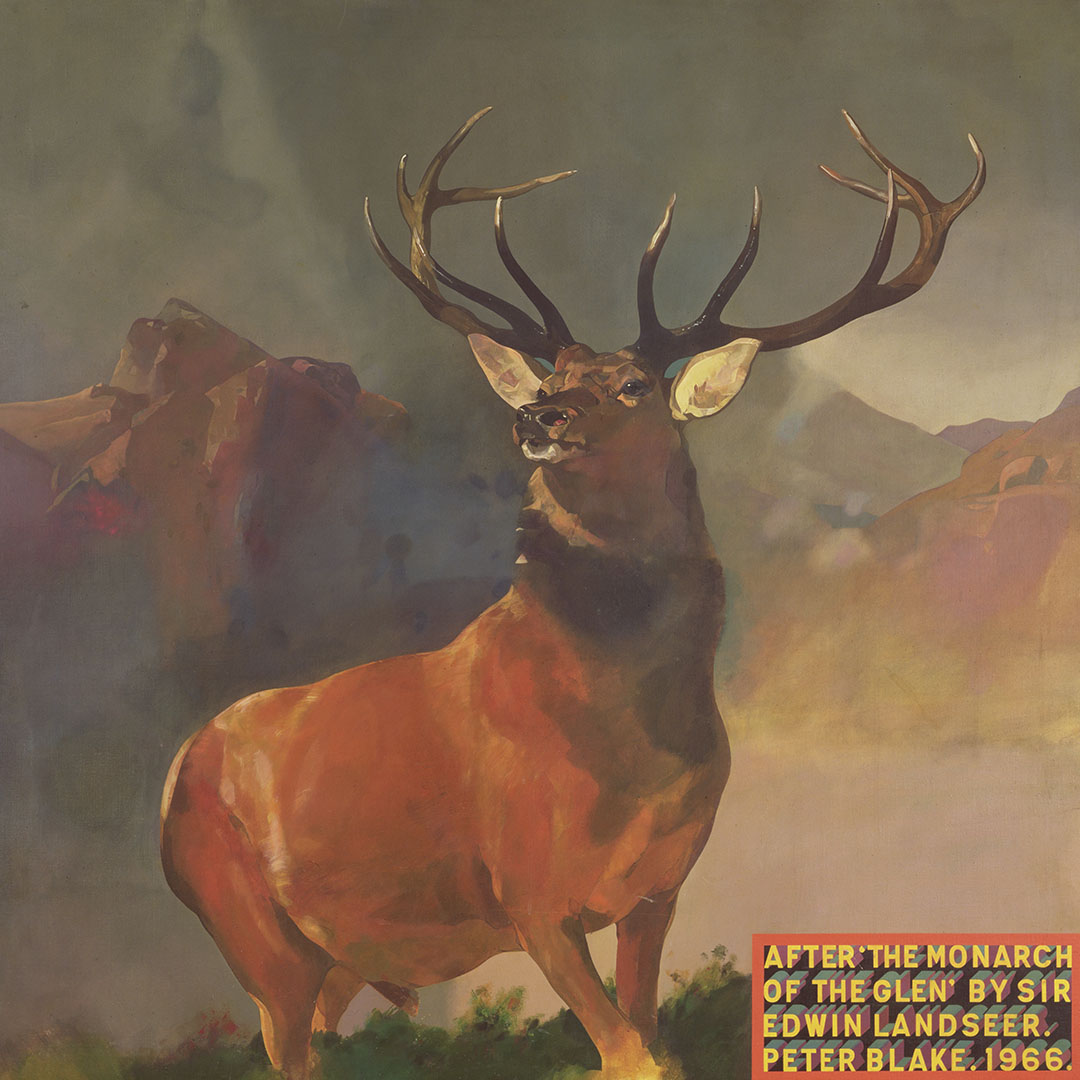

Undoubtedly, one of the most fascinating homages is the painted version created in 1966 by Sir Peter Blake, pioneer of British Pop Art for whom advertising was a key source. His work is respectful to the original, but the glowing typography of the painted label at the lower right confirms its status as a copy.

With Victorian art now enthusiastically rediscovered by the public and art historians, Landseer has been reassessed via exhibitions and books and his most famous work seems to have lost none of its ability to inspire. When the Scottish National Portrait Gallery acquired the photographic portrait of The Queen in a dramatic Highland setting, it was described in newspapers, perhaps inevitably, as ‘The real Monarch of the Glen’.

All this begs the key question: why is Landseer’s work such a successful image? The answer may lie in its fascinating history, but also, surely, in its boldness and simplicity and confrontational nature. It sets the stag in command of its environment and presents a challenge to the viewer or imaginary stalker.

Instantly recognisable, the image can be harnessed to suit many different agendas. The negative impact of all this is that we think we know the painting and it’s hard to look at it afresh. The most effective way of countering this is to forget all the reproductions for a moment and study the picture itself.

'Lions have become a trademark or symbol of Britishness, but the Monarch remains a supremely Scottish icon.'

Having toured Scotland since 2017, Land-seer’s Monarch is soon to be shown in the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square. This is doubly appropriate, as it was there that it was first exhibited in 1851 (at the time, the RA was located within the National Gallery) and also because it will be close to the other most public and affectionately regarded commission of the artist’s career: the great bronze lions at the base of Nelson’s Column that he designed in the 1860s.

In some respects, lions have become a trademark or symbol of Britishness, but the Monarch remains a supremely Scottish icon, recognised and admired far beyond the confines of the high Victorian art world from which it came.

Christopher Baker is director of European and Scottish Art and Portraiture at the National Galleries of Scotland. His book ‘The Monarch of the Glen’ was published in 2017. The exhibition ‘Landseer’s The Monarch of the Glen’ will be at the National Gallery, London WC2 from November 29 to February 3, 2019. For more information, visit www.nationalgallery.org.uk.

My Favourite Painting: HRH The Prince of Wales

HRH The Prince of Wales chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

Dumfries House: The house The Prince of Wales saved

Country Life pays a visit to Dumfries House to witness the renaissance of one of the finest mid-18th century country

HRH The Prince of Wales: Why we must save our trees

In his birthday message to the countryside, His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales urges us all to work together

Credit: John Paul Photography / Courtesy of Clarence House

HRH The Prince of Wales: Why we must save the countryside's soul

In his regular birthday message to the countryside, His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales stresses the need for balance

Credit: HRH The Prince of Wales, photographed by John Paul for the Country Life Picture Library

HRH The Prince of Wales: ‘We may be the last generation fortunate enough to experience the wonderful people, skills and activities of our countryside’

HRH The Prince of Wales has guest edited the November 14 edition of Country Life. In his leader article, he

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.