My Favourite Painting: Christopher Jackson

The poet and artist Christopher Jackson chooses 'a macabre picture, with marvellous details': Chatterton by Henry Wallis.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Christopher Jackson on his choice, Chatterton by Henry Wallis

‘Poor Chatterton. This is not only a wonderful picture, but a lesson to artists. Try not to die in a garret. In the wake of lockdown, the image of isolation seems pertinent. Outside of poetry and painting, my work now is helping young people with their careers. I never pass this painting without thinking on the virtues of compromise in life. It’s a macabre picture, with marvellous details: the expensive-looking trousers, especially. It has a tranquil sympathy that tells us that other options were available. The hero of the picture isn’t Chatterton; it’s the pot of flowers on the windowsill.’

Christopher Jackson is a poet, artist and member of the Finito Education management team. His latest book of poetry, An Equal Light, is out now.

Charlotte Mullins on Chatterton

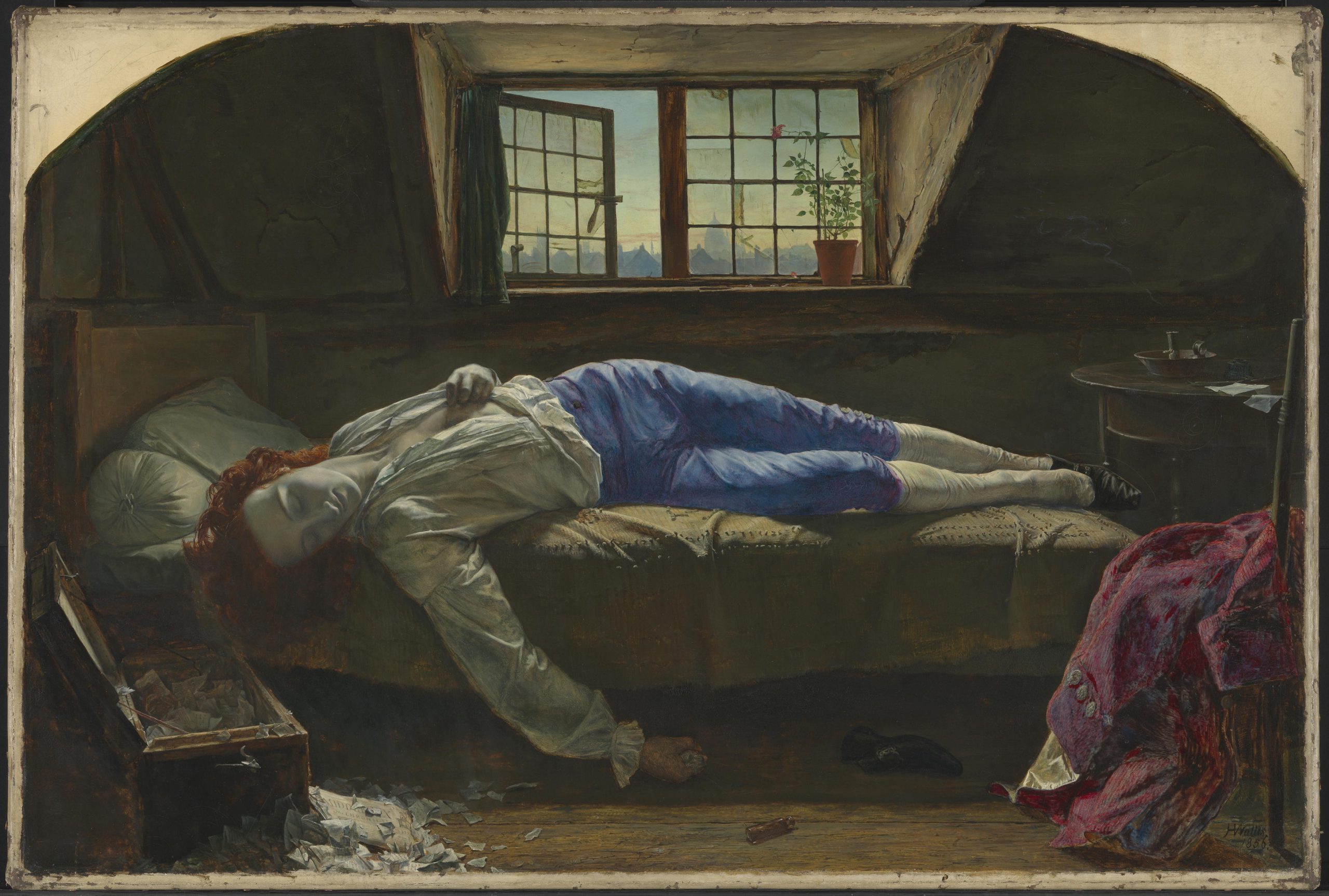

A red-headed man lies lifeless on a narrow bed, his arm grazing the floor, a phial of poison nearby. His right shoe has tumbled to the ground, but the rest of his body is clothed, his breeches glowing in the last of the day’s light. There is no money for a candle, no rug and the paint is peeling. The attic room’s small window is open and London’s skyline can be seen in the yellowing light. A fragile pot plant outlives the young man, its single bloom tender on a fragile stem, and his poetry lies in shreds across the floor.

Henry Wallis painted the 18th-century poet Thomas Chatterton in 1856, exhibiting the painting at the Royal Academy to great acclaim. It was the holy grail of a Pre-Raphaelite painting, one that was true to Nature both in how it captured the scene and in how it conveyed emotion. The room was a re-creation of Chatterton’s Brook Street attic, where he killed himself by drinking arsenic aged 17. No surviving portraits of Chatterton exist, so Wallis had free rein to conjure a ‘likeness’ that simultaneously conveyed the poet’s melancholy, his emaciated body and his romantic appeal as a doomed hero.

Wallis used novelist George Meredith as his model. His flame-red hair contrasts with his waxy white skin and blue breeches. These are the colours of British identity, of the Union Flag. The painting offered a sideswipe at the then government and its lack of support for young artists, by suggesting that the country was culpable for this death.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Charlotte Mullins is an art critic, writer and broadcaster. Her latest book, The Art Isles: A 15,000 year story of art in the British Isles, was published by Yale University Press in October 2025.