Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Emma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Man Alive, Hyde Park, the documentary filmmaker John Pitman’s dreamy 1971 chronicle of a day in the life of London’s largest green space, opens with a quintessentially British scene: goosepimpled early-morning swimmers taking gamely to the Serpentine. Among them is Ernest Marples, who was a Conservative MP (now chiefly remembered for introducing Premium Bonds and postcodes), but he is afforded no special treatment. Swimming, like queueing, is a national pastime which unifies.

It also calls on our reserves of bloody-mindedness: British swimmers have to use not only our arms and legs, but our imagination. The water may be cold enough to turn our toes blue and said toes may be tangled in pond-weed, but if the sun is out we feel ourselves being mentally transported to a Slim Aarons photograph. Leaving the everyday behind.

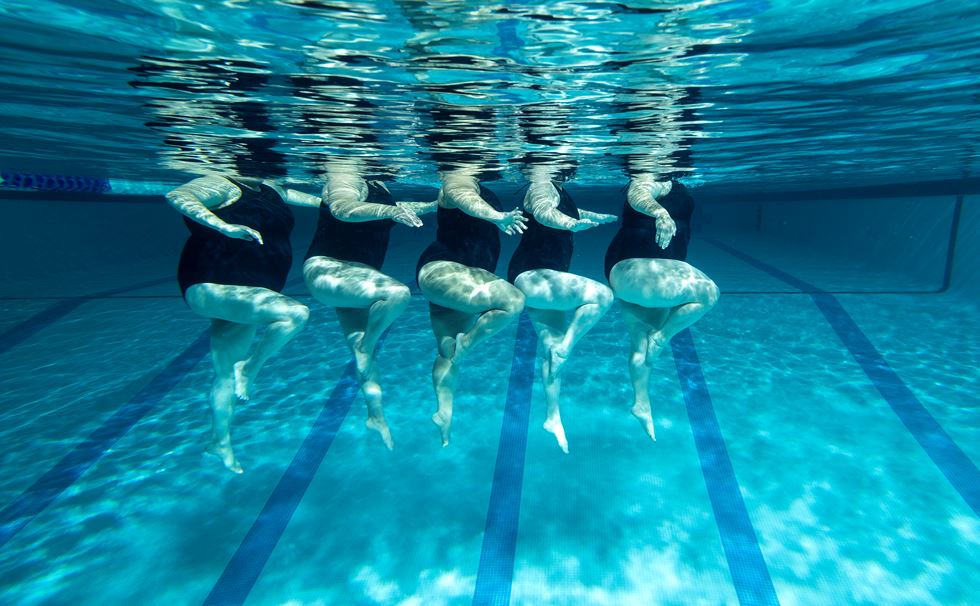

Just in time for the first ill-advised but exhilarating outdoor swim of the year, Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style, has opened at the Design Museum in Kensington. The curator, Amber Butchart, grew up paddling in the coastal town of Lowestoft, East Suffolk, and now swims regularly in Margate’s tidal pools in Kent.

She is fascinated by the aesthetics of swimming. ‘I love this idea of trying to contain nature,’ she says, which naturally raises the question of what we might be trying to do to, with or for ourselves when we take to the water. It’s one I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about.

Pamela Anderson's iconic red swimming costume from Baywatch is on display as part of the exhibition

In recent years I have swum to the Isle of Wight, across the Adriatic Sea for several hours non-stop, and most recently in icy Arctic waters. I am far from athletic and the swimming part has never come easily to me, but I feel compelled to keep doing it.

Divided into three sections – the pool, the lido and nature – Splash! starts with the early 1920s. Of course, Britons had been enjoying a dip long before then. The Romans initially brought baths to the country, swimming became a formally competitive sport in the early 1800s, and the 1846 Baths and Washhouses Act saw the construction of grand municipal baths to improve public health in cities following cholera epidemics. But a post-First World War focus on fitness and health saw us change what the majority of us did in the water.

The fashion house Jantzen branded one of its designs ‘the suit that changed bathing to swimming’. British beach holidays became aspirational; a North Eastern Railway poster promoting them is a triumph of hope over the experience of the British seaside, all primary colours and Hollywood swimsuit silhouettes.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Displayed next to this is Lucy Morton’s Gold medal from the 1924 Paris Olympics. Morton, a Blackpool-born Post Office clerk whose victory was eclipsed by the events which would inspire Chariots of Fire, had her own battles in the run-up to race day. Two days before the 200m breaststroke competition, the taxi in which the British ladies’ swimming team were travelling crashed, throwing Morton from the vehicle and costing her five of her teeth.

Her stoicism is echoed in images of early Channel swimmers, solitary figures in a terrifyingly vast expanse of water, and the shots of plucky aquanauts cracking the ice on the Kenwood Ladies Pond, the all-female oasis in Hampstead Heath. During the pandemic, entry to this became ticketed and timed: a necessity. But regulars (of which I am one) still miss the prelapsarian joy of wandering freely into the hidden glade and stripping down to our swimsuits.

The cold didn't put these regulars off at the women's pond at Kenwood on Hampstead Heath in 1935

‘When you swim, you feel your body for what it mostly is – water – and it begins to move with the water around it,’ the pioneering wild swimmer Roger Deakin wrote in his word-of-mouth bestseller Waterlog. ‘No wonder we feel such sympathy for beached whales – we are beached ourselves at birth. To swim is to experience how it was before we were born.’

The tension between the return to nature promised by swimming and the artifice often required to actually access it is hinted at in the room devoted to the lido boom of the 1930s. As well as being built in the middle of cities, aquatic amphitheatres were constructed around natural tidal pools in places like Penzance.

With well over 200 objects, Splash! is a gloriously eye-catching whistle-stop tour which can also, at times, feel a little surface-level in its analysis of the experience of actually being in the water. Deakin, to whom one could easily devote an entire exhibition, is given just one display case to outline his theory that swimming gives us access to a part of the world which, ‘like darkness, mist, woods or high mountains’ retains its mystery.

Happily, the exhibition concludes with a screening of two transporting 10-minute videos, one following South Korean female working free-divers (haenyeo) and the other on Swim Dem Crew, a London swimming club. Both are full of moving reflections on why we swim. “There are no rules,” one of Swim Dem Crew’s founders says, before going on to discuss the confidence he has gained from engaging with his fears of open water. ‘I felt that if I could do this I would be able to do anything,’ a young diver echoed.

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style is at the Design Museum, 224-238 High Street Kensington, London W8 6AG until August 17. Tickets from £14.38

Emma Hughes lives in London and has spent the past 15 years writing for publications including the Guardian, the Telegraph, the Evening Standard, Waitrose Food, British Vogue and Condé Nast Traveller. Currently Country Life's Acting Assistant Features Editor and its London Life restaurant columnist, if she isn't tapping away at a keyboard she's probably taking something out of the oven (or eating it).