What do 19th century rowers, Queen Victoria and Giorgio Armani all have in common? They helped to popularise the world's most versatile jacket — the blazer

Everyone from royalty to rappers seems to have one in their wardrobe. Harry Pearson lists the merits of the blazer, a true sartorial team player.

During Lent terms in the late 1820s, early-morning strollers on Midsummer Common in Cambridge may have spotted something alarming through the icy winter mist that hovered above the River Cam. Speeding towards them came a boat that was, or so it seemed at first glance, on fire.

Fortunately, it soon became clear that this was not some undergraduate version of a Viking funeral ship, but an ordinary rowing shell with a crew decked out in flame-coloured coats. Lady Margaret Boat Club had taken to wearing short flannel jackets to keep them warm during chilly training sessions: the 19th-century answer to the sweatshirt or tracksuit top.

It's hard to tell from this photo but Lady Margaret Boat Club's rowing team in 1890 was as red as red could be.

The bright hue had been chosen to honour Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII and founder of the rowers’ college, St John’s. Watching the fiery crew flashing across the water, an onlooker dubbed the new jackets ‘blazers’. The name stuck. Soon, other rowers were copying the jackets with their patch pockets and raised seams, as well as embracing the idea of bright colours. Regattas came to resemble the parade ring at Epsom, the blazers as bright and distinctive as jockeys’ silks. In an age of increasingly dark and restricted dress, the sporting blazer offered the Victorian gent a rare chance to show off a little.

In a blaze of glory

Fun fact: rowers in the Netherlands pride themselves on their grubby, ill-fitting and often threadbare blazers (above). Dutch rowing-club tradition dictates that the blazers are handed down from one generation to the next and must never be washed.

In Edwardian times, many British golf courses made it compulsory for players to wear red blazers: they were a form of hi-vis jacket that helped others to spot them and avoid anyone being beaned by a drive.

According to legend, the Cambridge Archetypals’ rainbow-striped blazer can be worn only by those who have rowed in three Oxford-Cambridge Boat Races, got a third-class degree and spent three nights in prison.

The current winner of the Augusta Masters golf tournament in the US is the only person allowed to remove one of the famous green blazers from the golf club grounds. He must return it when the next tournament begins.

Not everyone was enamoured: in 1888, the society correspondent of The Globe commented sniffily that ‘the blazers of the men were, in many cases, vivid, startling and hideous’, whereas, in 1893, The Sketch denounced them simply as ‘barbaric’. Next came a remarkable coincidence. A decade or so after Lady Margaret’s rowers had first worn their red blazers, Queen Victoria paid a visit to a Royal Navy steam sloop. At that time, there was no regulation dress for sailors and crews were kitted out at the whim of their captain (the sailors on HMS Tiger wore yellow-and-black striped jerseys). In honour of the royal visit, the captain of this particular sloop had his crew kitted out in short double-breasted blue coats with brass buttons, based on the traditional sailors’ reefer jacket. Her Majesty was impressed and, in time, the jacket would become part of the Royal Navy uniform. It was named in honour of the ship on which the queen had approved it: HMS Blazer.

Thus it was that, in the space of a decade, the British gained not one, but two jackets that would become a staple of the national wardrobe. They had little in common — one was a sober authority figure, the other a garish gadabout — yet they shared a name. It was the sporting blazer that initially held the upper hand in this sartorial sibling rivalry. Members of golf, rugby, association football and cricket clubs all adopted blazers in home colours. It also became the preferred jacket of the Olympic Games, where it appeared in myriad shades from Japan’s rising-sun red in 1964 to the cerulean blue of South Korea in 1988.

Korean Olympic officials raise the Olympic torch before lighting the Olympic flame during opening ceremonies for the 1988 Summer Olympic Games in Seoul.

The bright colours would eventually see the sporting blazers fall from favour, although it has recently enjoyed a renewed burst of fashion ability thanks to US international rower Jack Carlson’s company Rowing Blazers. There has always been opposition to men wearing blazers at sporting events in which they are not involved — in fact, The Yorkshire Post commented in 1894 that ‘when a man not actually engaged in a boat race or a cricket match wears a blazer he is a bounder’. It has to be said that the blazer, particularly the military version with regimental buttons, has a certain caddish reputation: archetypal British blackguards Terry-Thomas and Leslie Phillips were rarely seen in anything else. The blame lies not with the jacket per se, but with its occasional appropriation by the wrong crowd. ‘Like the firm handshake and looking people straight in the eye, the blazer had originally been a symbol of trust,’ satirist Craig Brown once stated in a newspaper column. ‘Because of this, it has been purloined by the less than trustworthy and became their preferred disguise.’

Pete Townshend in 1966 performing with The Who.

Katharine Hepburn enjoying a cigarette during a press conference in Southampton in 1952.

The fashion for double-breasted navy blue or black blazers with metallic buttons, often regimental and sometimes paired with a crest on the breast pocket, originated with army officers in the aftermath of the First World War. German style writer Bernhard Roetzel, author of Gentleman: A Timeless Guide to Fashion, found the look ‘slightly stagy… suggesting some kind of Ruritanian uniform’. Yet, despite his misgivings, when he visited Cordings in Piccadilly in the 1970s he was told by one of the staff that such blazers, paired with mid-brown cavalry twills, had become ‘the English uniform’. Today, the blazer’s adaptability allows it to occupy both ends of the fashion spectrum, to be both respectable and rebellious. It has been the province of naval officers, football referees, William Brown and the Outlaws and 1960s Mods (Pete Townsend of The Who even made one from a Union Flag).

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

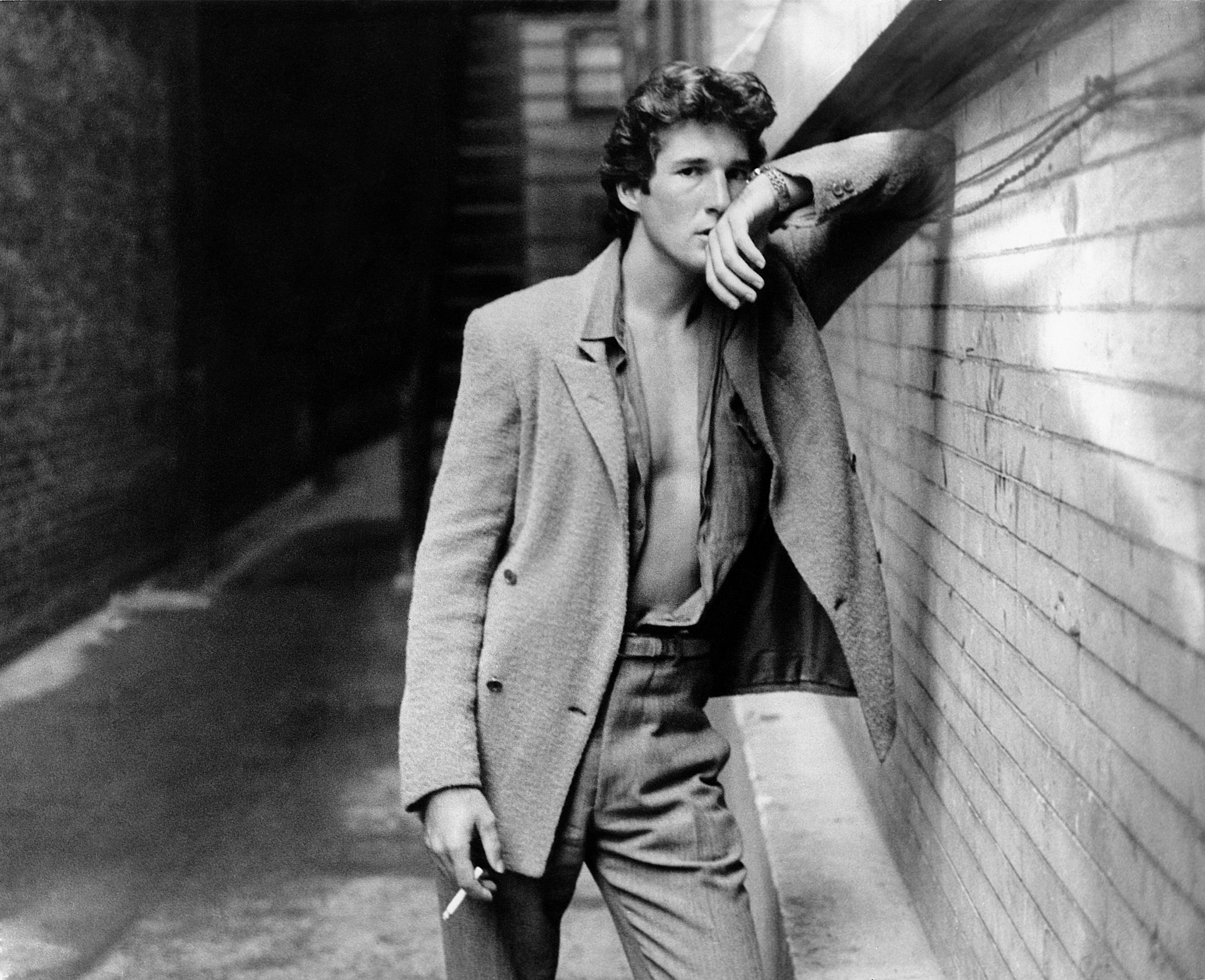

It can be worn — in its unstructured Giorgio Armani form — by amoral Richard Gere in American Gigolo and by the chief umpire at Wimbledon, by The King and Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols, Prince George and rapper Drake. As the American style writer Alan Flusser notes: 'The classic blazer remains man’s most accommodating tailored companion.'

Johnny Rotten, the lead singer of the Sex Pistols on tour in Arnhem, Holland in 1977.

Not only man’s, of course, but mankind’s. For the blazer became a fashion item among women back in the 1890s: in 1893, Vogue noted that fashionable women were to be seen wearing blazers with white-facings paired with a ‘perfectly plain skirt’. In 1900, the jacket was an integral part of the look of the New Woman and soon became so associated with the fight to get women the vote that it would, when paired with a long skirt and sash, form part of ‘The Suffragette Suit’. Elegant French tennis star Suzanne Lenglen, the greatest female player of the 1920s, wore a blazer over her tennis whites at Wimbledon, creating a trend. Later, the blazer would form part of the glamorous, androgynous 1930s wardrobes of Marlene Dietrich, Katharine Hepburn and Lauren Bacall. In the 1950s, the jacket would lose ground to the less formal cardigan, only to pop up again at regular intervals.

The actor Timothée Chalamet has been known to rock a blazer (shirt seemingly MIA) on the red carpet.

Championed by Yves Saint Laurent, sharply cut blazers were worn by Jackie Kennedy and Audrey Hepburn in the 1960s and in the power-dressing 1980s by Diana, Princess of Wales and Margaret Thatcher. Lately, the actor Timothée Chalamet has been spotted wearing a blazer with no shirt at all — not a look that would suit all of us, admittedly. However, whatever your body shape and however the rest of your wardrobe may be filled, the supremely adaptable blazer is your friend. It is a true team player, a symbol that the wearer is part of something greater than his or her self. Whether a club or naval garment, the blazer, Italian tailor Eduardo De Simone wrote, ‘is an item of clothing that represents a feeling of belonging’. It is a jacket that feels like home.

This feature originally appeared in the June 25, 2025 issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe

Harry Pearson is a journalist and author who has twice won the MCC/Cricket Society Book of the Year Prize and has been runner-up for both the William Hill Sports Book of the Year and Thomas Cook/Daily Telegraph Travel Book of the Year.