Time to join the fan club: the history of this summer's must-have accessory

As summer temperatures continue to soar, fans — long considered a fashion anachronism — are back in the style spotlight.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

'Since summer first was leafy, man has reached for a branch of a tree or a large leaf to dispel the heated air and ward off flies,’ wrote MacIver Percival in The Fan Book more than a century ago. Early civilisations went an artistic step further and created ceremonial fans, two of which were discovered in Tutankhamun’s tomb. Personal folding fans as fashion accessories were present in Japan from about the 6th century. Percival, however, was writing in 1920, by which time usage was on the wane; his book was aimed at collectors.

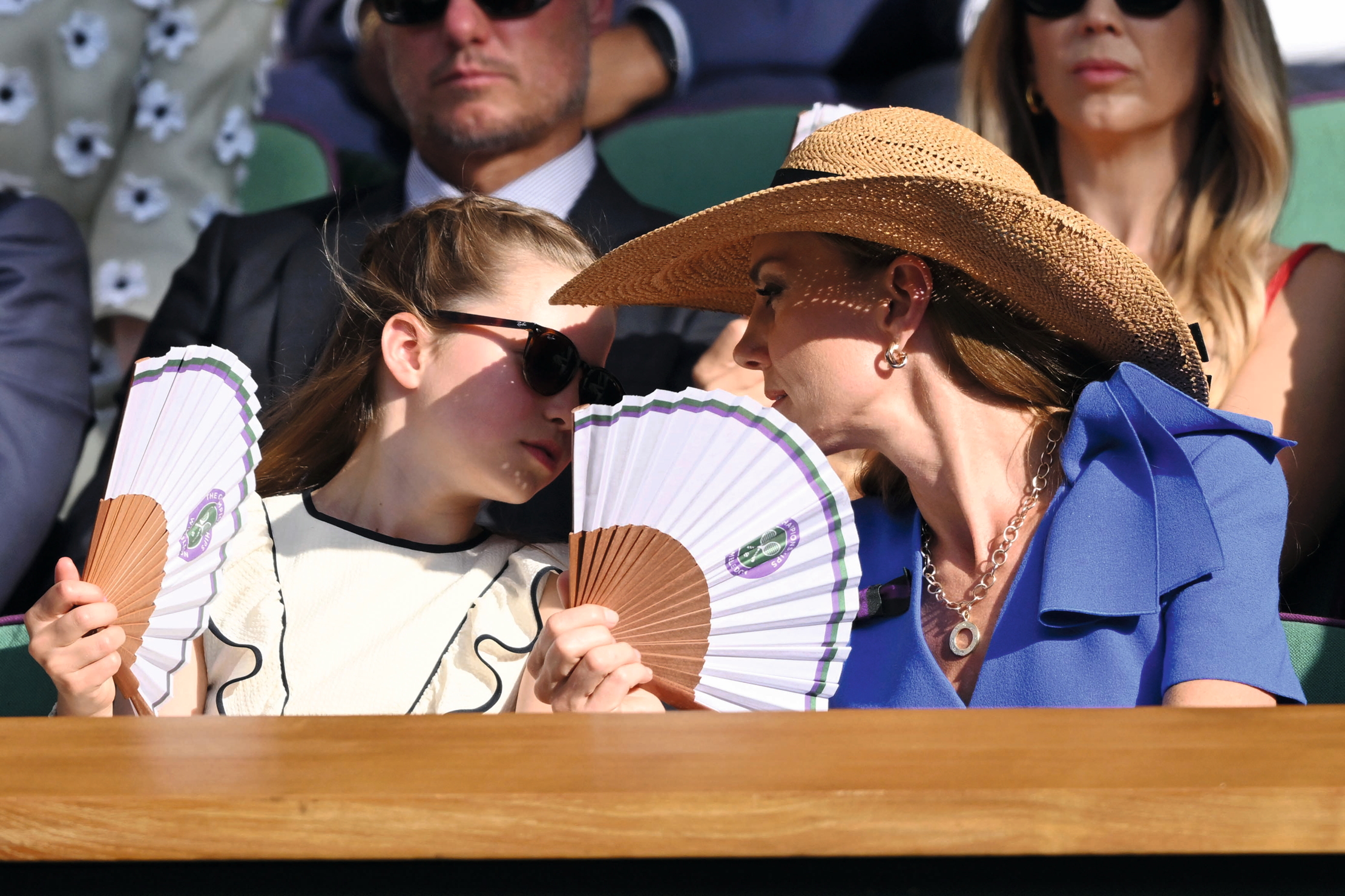

Yet fans, it seems, are back: they have been observed once again on public transport during this scorching British summer, compensating for ill-equipped air-conditioning systems. They were spotted at this year’s Wimbledon Championships, at the Lord’s Test and, a colleague confirms, at Glastonbury.

An old-school print journalist might reluctantly attribute this to the declining habit of buying newspapers, a reckless oversight, as the good old daily rag can be swiftly repurposed in emergencies as a fan (or even as a hat). There is, however, something timelessly elegant about a daintily fluttered hand fan. With temperatures set to rise for the foreseeable future, has the fan’s time come again?

Fans arrived in Europe via medieval trader — and crusader — travels to the Far East. North Italian cities were developing an independent fan-making industry from the 15th century. A Titian portrait shows a lady holding a small flag fan, perhaps reflecting his native Venice’s specialisation in the craft. Florentine-born Queen Catherine de’ Medici of France (1519–89) delighted in both feather fans — which had handles, sometimes with a mirror in the centre — and folding fans. It was enough to elevate their status to that of essential costume accessories for noblewomen. Their use soon spread to the English Court; paintings of Elizabeth I show her holding both types of fan. Subsequently, young men on Grand Tours brought back painted folding fans for their ladies, invariably depicting famous Italian sights, such as Rome’s Tiber Bridge and Venice’s Piazza San Marco, or romanticised peasant scenes.

By the 18th century, France was the centre of European fan production and designs shifted to echoing the frivolous Rococo subject matter of artists such as Watteau, Boucher and Fragonard. English fan-makers, their numbers boosted by an influx of refugee Huguenots, tended to follow French trends, although topical fans were also produced, ranging from the celebratory (Nelson’s 1798 victory at the Battle of the Nile) to the commemorative (the death of George III in 1820).

'A London academy offered training to women on the use of fans, as well as to males on the methods of ‘gallanting’ them, with success guaranteed after 40 lessons'

The manner in which a fan was borne became a matter of considerable significance. Queen Charlotte, consort of George III, was not noted for her beauty, but the painter James Northcote, on seeing a portrait of her, let out a nostalgic sigh and exclaimed: ‘Lord, how she held that fan!’ Early in the 18th century, Joseph Addison wrote in The Spectator of how ‘women are armed with fans as Men with swords’ and that ‘the Fan is either a Prude or a Coquette according to the nature of the person who bears it’. A London academy offered training to women on the use of fans, as well as to males on the methods of ‘gallanting’ them, with success guaranteed after 40 lessons.

Fans continued to enjoy great popularity through the 19th century. However, although they subsequently came to be seen as old-fashioned, not all now share that view. Mass-produced fans are cheaply acquired online, coming in various materials, colours and patterns, some evoking the traditional Oriental designs. Meanwhile, the fashion market is embracing higher-end designs.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Caroline Allington of the Fan Museum in Greenwich featured in Country Life in 2017.

In 2014, Denise Frankel and sister Janis co-founded the first fan-making company in London for a century, offering ready-to-wear and bespoke hand fans. Its name, Rockcoco, is at once a playful nod to the Rococo period (from about the 1730s to 1770s) and to the burst of bold energy inherent in modern rock music. The combination is exemplified in one of the Frankels’ most striking designs, the Constance fan, a collaboration with accessories designer Rory Hutton, which adds a contemporary flourish to typically Rococo patterning.

‘I’ve always used vintage hand fans to accessorise vintage eveningwear,’ says Denise. ‘However, I was finding that, due to their age, they were very delicate and some broke. There was no real alternative in the contemporary market. After being constantly asked where I’d bought mine, it dawned on me that if no one else was making them I was going to have to do it.’ Luckily, her sister — who had a background in accessories, having worked in their father’s City of London millinery company, a business started by their grandfather — was equally passionate.

However, with fan-making in Britain now on the Heritage Crafts Association Red List’s critically endangered category, the sisters had to travel to Spain to find suitably skilled artisans. They even managed to track down one woman in her nineties still able to make double-sided fans, a type generally only found now as an antique.

For Denise, each era of fan-making has its own charm. Although she delights in the way those of the Rococo period ‘blended art, fashion and a little bit of fun’, she has a soft spot for the bold graphics of Art Deco era fans. ‘They have clean lines, geometric patterns and luxurious materials, such as tortoiseshell gold, lacquered wood and my favourite, ebony. It’s a style I find incredibly wearable, even today.’

The Princess of Wales and Princess Charlotte used fans to cool off at this year's Wimbledon Championships.

A sense of the rich diversity of fan types and designs and their place in history and culture over the centuries is gained from a visit to the Fan Museum in Greenwich, London SE10, which also stages ever-changing exhibitions. Looking to the future, the Worshipful Company of Fan Makers, which received the Royal Charter in 1709 to regulate fan-making standards, has been working to revitalise the craft in this country through its Heritage Crafts Committee.

Antony Robson, the livery company’s Master, reveals that the company has forged a link with The King’s Foundation, set up in 1990 to promote and teach traditional arts and crafts. Aiming to address the fact that modern haute couture and middle-market fans only come from a slim number of overseas sources, he adds that this is the fifth year the company is working with University of the Arts London/Chelsea College of Arts BA hons and MA product-design students on a ‘Rethinking the Fan’ project. ‘We are also at an advanced stage in our latest project, to develop a certified diploma in fan-making with West Dean College in West Sussex.’

Denise is a member of the company and of its Heritage Crafts project team and says she’s proud to be ‘doing her bit’ to aid the revival of British fan-making. ‘I do feel people don’t take hand fans seriously as an accessory,’ she laments. ‘I regularly notice women impeccably dressed, with designer shoes and handbags, but then out comes an old mass-produced fan that in no way complements the outfit. Carrying a fan for me has always been about function, as well as fashion. It’s a beautiful accessory, yes, but also something wonderfully practical that I simply couldn’t be without.’

Jack Watkins has written on conservation and Nature for The Independent, The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph. He also writes about lost London, history, ghosts — and on early rock 'n' roll, soul and the neglected art of crooning for various music magazines