Just can't get enough of the muff? The history of the furry handwarmer with the funny name

Deborah Nicholls-Lee goes diving into the history of the muff.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If the Victorian Christmas card had a tick list of favourite features, cherubic girls warming their hands in soft fur muffs would rank highly. Yet the muff can be traced further back — perhaps to the sheepskin hand coverings used by monks more than 1,000 years ago — and certainly to the 16th century, when sleeves began to recede and sumptuous muffs, suspended on a chain from the girdle, became the fancy ornaments of the nobility.

The Victorian journalist and author Frank Hird, writing in The Girl’s Own Annual of 1896 was an ardent enthusiast. ‘Of all the accessory details of feminine toilette, the muff is the most fascinating. Be it of costly fur, a triumph of millinery, a piece of twisted velvet with coquettish bows of ribbon inconsequently placed here and there, or of plain cloth demurely braided and corded, with wise-looking tassels, it is always an incident in [a] woman’s appearance that cannot be overlooked,’ he gushes. He attributes the invention to an unknown Venetian woman of the late 1400s, who ‘appeared in public one winter day carrying a rolled piece of velvet lined with fur, its two ends fastened with crystal buttons’.

From here, the trend made its way to France, suggesting that its English name may originate from moufle, meaning mitten. The trend later ventured north and words such as mof, meaning sleeve in Dutch, hint at the muff’s tubular shape as well as its precursor: a thick fur cuff into which a hand could retreat.

Gabrielle Dorziat, a french actress, at Theatre Du Vaudeville in Paris in the 1800s.

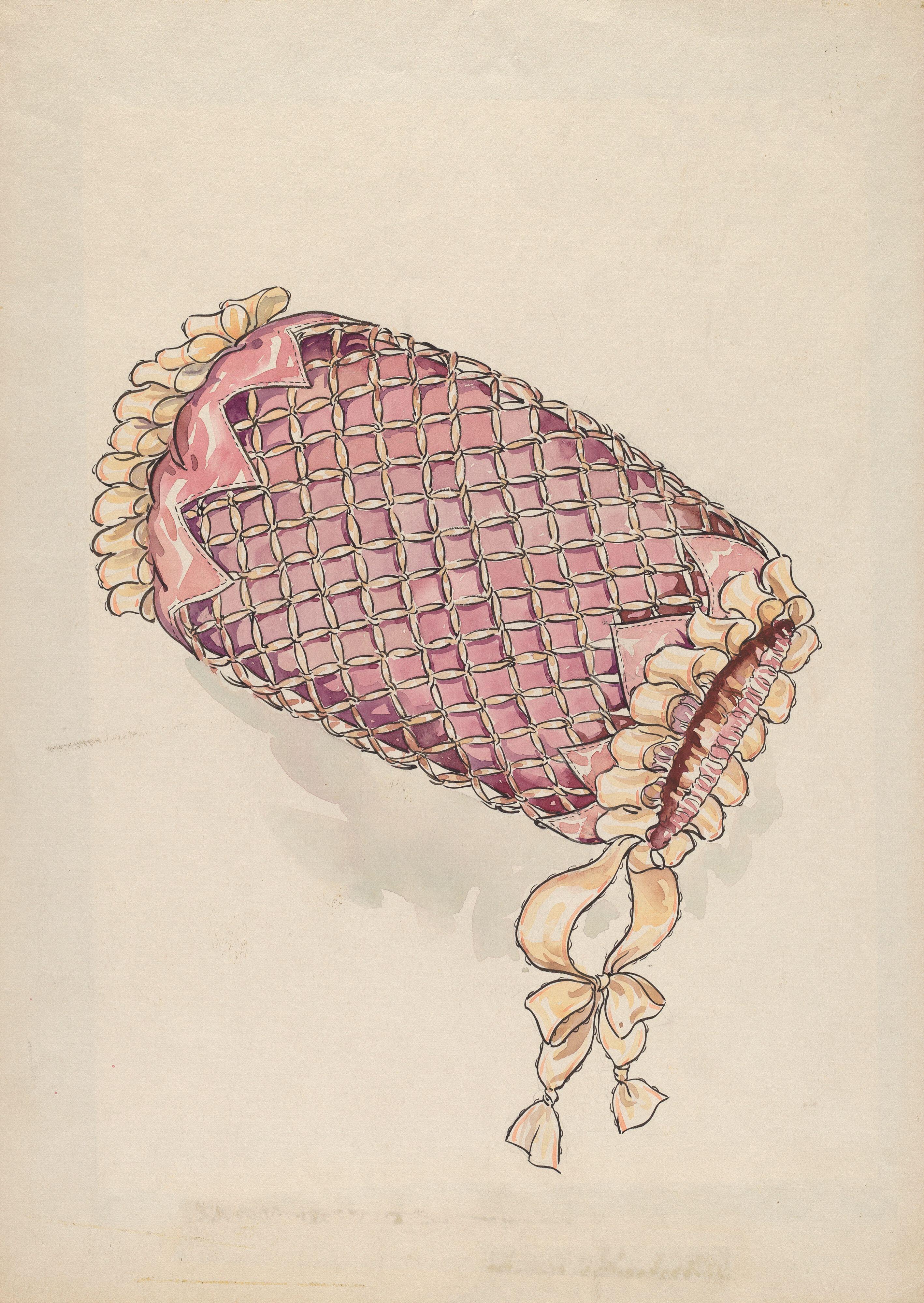

A muff created by Lillian Causey around 1936, demonstrating mid-1930s fashion design.

The muff’s saucy double meaning was already at play in the 1700s and may be hinted at in Henry Fielding’s episodic novel The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling. Here, one belonging to Sophia Western is a symbol of the romantic love between her and Tom, who kisses it passionately in her absence and declares it ‘the prettiest muff in the world’. By contrast, in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, the muff denotes wealth rather than feeling when the materialistic Mrs Allen invites an obliging James Morland to guess the price of her latest purchase.

Whereas Morland may have had to feign interest in Mrs Allen’s new muff, many important male figures have gone so far as to add it to their own wardrobes. According to Hird, Henry III of France (1551–89), a renowned fashionista, was an early adopter of the muff and ‘sheltered his hands in masses of ribbon laced together with gold thread with heavy fringes thereto of twisted gold and jewels’. The 17th-century diarist Samuel Pepys was more than satisfied with his thrifty foray into the fashion, writing: ‘This day I first did wear a muffe, being my wife’s last year’s muffe, and now I have bought her a new one, this serves me very well.’

Across the Channel, Louis XIV reportedly made a more decadent choice, opting for a muff made of tiger’s fur. Lower down the social scale, some accounts suggest that even executioners made use of fabric muffs, ensuring their hands were warm enough to undertake their grisly task. Yet, not everyone liked to see men with muffs. A 1735 print complains that the fey dandy depicted seems a little too delighted with his highly decorative version and a caption in French invites him to cast off the effeminate accoutrement and instead warm himself in a woman’s embrace.

With the muff firmly back in female hands — or female hands back in the muff — there was no less exhibitionism. By the turn of the 19th century, this fluffy status symbol had inflated to ludicrous proportions, dwarfing its owners, who waltzed around with hand warmers the size of sheep, inviting the admiration of fashion illustrators and the mockery of cartoonists.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Diana Jones modelling a fox head hat and muff in 1954.

Woodrow Wilson visits Buckingham Palace during a 1918 trip to England. Left to right: Edith Bolling Wilson, Queen Mary, Woodrow Wilson, King George V, and Princess Mary.

Whether large or small, fur was once the obvious choice for the muff and offered numerous possibilities. ‘Today the monkey, blue fox, beaver… and ermine are metamorphosed into Muffs; tomorrow will come the furs of sable, of otter, of chinchilla, of squirrel, of marten, of wolf…,’ remarked 19th-century writer Octave Uzanne in 1883, lamenting ‘the inconstancy of la Mode’. In place of fur, many ladies chose delicately embroidered or beaded fabric, sometimes featuring mezzotint portraits. They lined them with velvet, satin or silk and twinned them with a matching tippet, dress or cloak.

In the 1860s, feathers came to the fore, crossing from France into England, much to the dismay of British commentators, who saw it as a deliberate attempt by the French, having lost Canada to the British, to undermine its lucrative fur trade. Ranging from creams and browns to gaudy reds and blues, the outlandish designs both delighted and appalled.

Many muffs were not only a vision to behold, but smelled wonderful, too. ‘Some became veritable scent-bags, perfumed with heliotrope, rose, gardenia, verbena, violet, or they were powdered inside with orris root or poudre à la Maréchale,’ notes Uzanne, in his extensive eulogy on the muff.

Designed first and foremost to keep a lady warm on a walk or in her carriage, many offered additional functions. ‘Some muffs incorporated pockets to hold small items, such as handkerchiefs, and in the 19th century, muff bags or purse muffs made a brief appearance,’ explains Beatrice Behlen, senior curator of fashion and the decorative arts at the London Museum, where the collection includes a silk-lined cream skunk fur muff (1870–1900) made for Queen Victoria’s daughter Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll.

Some ladies even placed beloved lap dogs in muffs, carrying them around like little dolls. However, Suffragette Mary Richardson was less sentimental. She concealed a meat cleaver in hers to slash Diego Velázquez’s painting The Toilet of Venus (the ‘Rokeby Venus’) at the National Gallery in protest at Emmeline Pankhurst’s arrest; whereas Edith Garrud, a Suffragist-cum-martial arts expert, used hers to smuggle wooden clubs. Some women hid delicate pistols in there for self-defence against highwaymen and others simply popped in a small ceramic bottle of hot water to help keep the cold at bay.

Marlène Dietrich in the film 'The Scarlett Empress Year' in 1934.

A pair of muff pistols.

Now that women had secured the vote and were increasingly undertaking paid work, they rolled up their sleeves and cast off the muff as a symbol of feminine passivity at odds with the new era. ‘Muffs seem to have been largely abandoned after the Second World War,’ notes Behlen, a muff aficionado, who nevertheless acknowledges its shortcomings. ‘They are not the most practical of accessories and were probably only ever carried by men and women who did not have to work for a living.’

The streamlined silhouette of the 1960s seemed to have killed off the muff for good. However, by the 1980s, it was making sporadic appearances, with several of Princess Diana’s ensembles featuring the forsaken item. The accessory has refused to be stifled ever since, reappearing at regular intervals in surprising new incarnations: in neon orange shearling for Celine in 2014; in tartan for British brand Shrimps in 2020; and in shaggy black faux fur for Anna Sui’s Autumn/Winter 2025 ready-to-wear collection, which takes ‘madcap heiress’ as its theme. Fashion followers and fans of Sex and the City may have noted that when Mr Big finally tells Carrie, ‘you’re the one’ in the season six finale in Paris (2004), her iconic eau de nil tutu is paired with a cosy brown fur muff.

Which all begs the question: could the muff ever make a major comeback? ‘Muffs are difficult to incorporate into modern life,’ responds Behlen, with a degree of regret. ‘Having said that, I always fancied a muff made of padded nylon, like a puffer jacket. Particularly if it could have a little pocket for my phone.’

This feature originally appeared in the December 10, 2025 issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe.

Deborah Nicholls-Lee is a freelance feature writer who swapped a career in secondary education for journalism during a 14-year stint in Amsterdam. There, she wrote travel stories for The Times, The Guardian and The Independent; created commercial copy; and produced features on culture and society for a national news site. Now back in the British countryside, she is a regular contributor for BBC Culture, Sussex Life Magazine, and, of course, Country Life, in whose pages she shares her enthusiasm for Nature, history and art.