The lives, luxuries and lasciviousness of past and present gentleman racers

Cigars and brandy during pitstops may be a distant memory, but there are still those who pay for the privilege of being behind the wheel. Adam Hay-Nicholls joins the indulgent and hedonistic ranks of the gentleman racer.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There’s an old Fry and Laurie sketch in which Stephen Fry interviews a taciturn racing driver. Growing increasingly frustrated with the sportsman’s lack of enthusiasm, Fry eventually screams: ‘You do a job that half of mankind would kill to be able to do and you can have sex with the other half as often as you like – I just need to know if this makes you happy!’

Hugh Laurie’s character was blatantly based on Michael Schumacher. I’ve reported on Formula 1 for the past 15 years, beginning during the Schumacher era. The sport had long been professional, with ambitious young men committed to extracting as much from themselves as their machines in pursuit of thousandth-of-a-second gains. Cigars and brandy during pitstops have long been consigned to the history books.

Even those paying for the privilege of racing – and there are many – have to pretend they’d rather be somewhere else. Once known as ‘gentleman racers’, they’re now called ‘pay drivers’ – a less courtly, but more accurate, epithet. One of this season’s Williams F1 cars is piloted by 20-year-old Lance Stroll, by virtue of his father being a billionaire. You’d never know of his good fortune, because all the lad does is moan.

'Count Louis’ Chitty Chitty Bang Bang was so loud it was banned from Canterbury.'

I’d always wanted to race cars and, this summer, I took part in my first championship season behind the wheel of a Ginetta G40; a gravel-voiced and featherweight, apex-seeking weapon.

My role models are the swashbuckling risk-takers of yore, who prioritised style, fun and fair play over winning. Handily, by affixing a pocket square to my fireproof overalls, attention could be diverted from the fact I’ve never scored pole position.

Racing drivers used to have the time of their lives, because they never knew when that life would be extinguished. Prior to the 1980s, sex was safe and racing was dangerous. These chaps were of the same spiritual bloodline as those who’d flown fighter planes decades before, but it was before the Second World War that the cult of the gentleman racer really became something to behold.

Author Ian Fleming was transfixed when, as a schoolboy, he stood beside the banking at Brooklands and watched Count Louis Zborowski tear past at 120mph. An American raised in Kent, Count Louis had inherited £11 million in 1911 (£1.23 billion in today’s money), when he was 16, following the death of his parents.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

His father, who was killed racing cars, owned seven acres of Manhattan and his mother was an Astor. The homestead was Higham Park and our hero built houses there, which he’d then blow up using tons of explosives, just for the entertainment of his assembled guests.

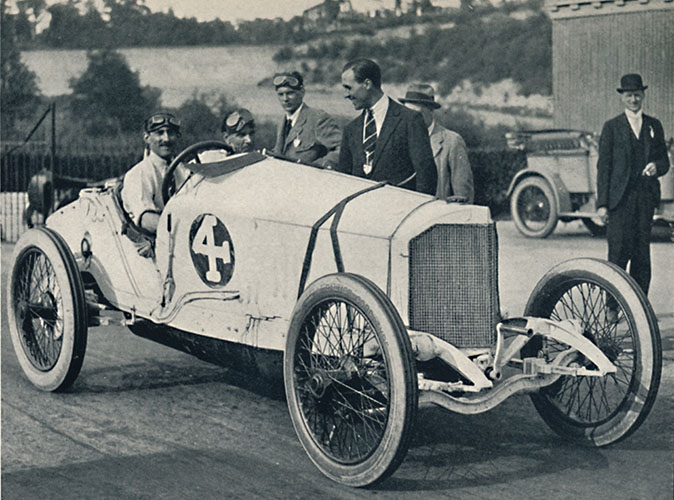

Count Louis also constructed his own automobiles in the stables. The car in which Fleming saw him take victory at Brooklands was a homemade, 23-litre Maybach-engined beast christened Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, inspiring the subsequent children’s novel and musical film. The machine was so loud it was banned from passing through Canterbury.

The archetypal rake, with slicked-back hair, ’tash and a cigarette still on the go when the green flag dropped, Count Louis’ fate was much the same as his father’s: he was killed 44 laps into the 1924 Italian Grand Prix.

Well-heeled amateur enthusiasts made up entire starting grids at this time and many had interesting backgrounds and sidelines – there were Olympians, spies, industrialists and royals. When not on the track, they were often to be found in the casino. Gambling was the thread running through everything they did.

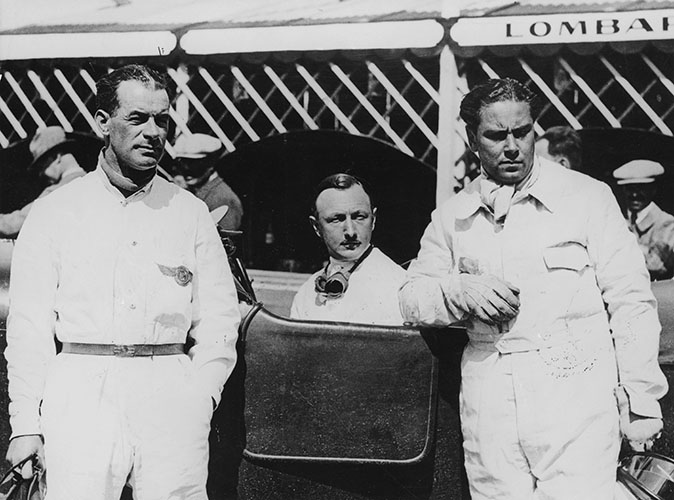

Three-times Le Mans 24 Hours winner Woolf ‘Babe’ Barnato wasn’t just one of the immortal Bentley Boys, he was the money behind the manufacturer. Like Count Louis, he’d inherited his millions as a teenager, thanks to his ‘Randlord’ father’s diamond and gold mines. Following First World War service as a field-artillery captain, he kept wicket for Surrey and began racing Bentleys.

'For racing on public roads, the French authorities promptly fined him a sum in excess of his winnings.'

In addition to his success at Brooklands and La Sarthe, Babe is best known for a £200 bet he put on beating Le Train Bleu in his Mulliner-bodied Speed Six saloon from Cannes to Calais in 1930. In fact, the Old Carthusian upped the ante: by the time the locomotive pulled into the French port city, he would be in St James, nursing a single malt.

He drove from the Carlton Hotel to the Carlton Club – 830 miles, 29 of which were on the back of a cross-channel ferry – in 22 hours and 30 minutes, beating the train to its destination by four minutes. For racing on public roads, the French authorities promptly fined him a sum in excess of his winnings.

Scotch whisky heir Rob Walker went as far as to cite his occupation as ‘gentleman’ in his passport and, when pressed, described himself as self-unemployed.

In 1939, competing at Le Mans in a Delahaye previously raced by Thailand’s Prince Bira, the 21-year-old Walker eschewed his overalls for a dark-blue pinstriped suit and tie for his evening stint, then swapped it for a more informal Prince of Wales check for his 12-hour-long marathon drive the following day. Having crossed the line eighth, he then drove another 150 miles to Paris and partied all night long.

Walker’s main legacy was running Stirling Moss in his privately entered blue-and-white Coopers, Ferraris and Lotuses in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but it was his delinquent adventures that confirm the legend.

In Wodehousian style, the Old Shirburnian kept a policeman’s helmet, which he’d whipped off a bobby’s head, in his study and he had his flying licence restored during the Second World War, after the Air Ministry had banned him for life for jumping the fences at a steeplechase in his Tiger Moth.

The thrill of racing was heightened by a mood of indulgence and hedonism. James Hunt was said to have entertained 33 British Airways hostesses in his suite at the Tokyo Hilton on the eve of his 1976 world-championship victory. He raced with a badge sewn onto his overalls that read ‘Sex, the breakfast of champions’.

Come the mid 1980s, the top echelons of motorsport still attracted men of private means, but the financial stakes were such that they couldn’t be seen to mess around anymore.

A descendant of Robert the Bruce and Queen Victoria, John Colum Crichton-Stuart, Earl of Dumfries – Johnny Dumfries, as he styled himself at the time – dropped out of Ampleforth at 16 to pursue motor racing.

Despite the some £100 million worth of land, property, art and furniture he was set to inherit, the Earl toiled as a builder, painter-decorator and van driver for the Williams team in order to raise funds. He wore an earring, had a thistle tattoo and a fake Estuary accent, because he didn’t want anyone to think he had a silver spoon and was merely dabbling in the sport.

The Scotsman’s talent became clear when he took the British F3 title in 1984, with 14 victories, before going on to race alongside Ayrton Senna in F1 and win Le Mans with 1988’s iconic Silk Cut Jaguar XJR-9LM. When he inherited the title of 7th Marquess of Bute in 1993, everyone in the pitlane thought he’d been given a pub to run.

Senna himself was from a wealthy São Paulo family, but it was he who ushered in a new era of professionalism. Charismatic but aloof, he was compassionate off-track, but utterly ruthless on it.

His commitment in and out of the cockpit and his win-at-all-costs attitude is mirrored to a large extent by today’s scowling young racers. Despite having nothing but respect for Senna, it’s hard not to yearn for the characters of old and their carefree approach.

In the Ginetta championship in which I’ve been competing this year, fighting the steering to a chorus of engine revs and wheel spin, you can bet that the rivals with whom I’ve jousted around the bends are inspired by the uncompromising styles of Senna, Schumacher, Sebastian Vettel and Lewis Hamilton. High heart rates mean that, by the time we arrive at the first corner, we’ve already sweated buckets through our thick Nomex overalls.

Given the choice, however, if the rules would allow, I’d take a leaf out of Walker’s book and choose a double-breasted Savile Row ensemble, heel-and-toeing down through the gears in my brogues.

The thrill of racing wheel-to-wheel needn’t be a pipe dream. The Ginetta Racing Drivers Club has enabled me to race at Rockingham, Snetterton, Silverstone and Brands Hatch this year, for less than the cost of joining a good golf club.

The price for the season is £42,000 and you get to keep the car at the end. Alternatively, you can do ‘arrive and drive’ for just £9,000 for the season.

A mechanic is provided to do all the oily stuff. The cars are identical: Ginetta might sound like an Italian ice cream, but these machines are made in Yorkshire. The fibreglass automobile weighs just 840kg (1,850lb), meaning it handles like a dream.

Between its nose and your legs sits a high-revving, 1.8-litre Ford Zetec engine, producing 135bhp. Forget traction control and ABS; the only driver aids are your hands and feet.

Despite the chunky roll cage, cockpit fire extinguisher and the three buttons you need to press just to start it, this sports car sits on regular tyres and is road legal, meaning you can drive yourself to races. Be careful how you go or you won’t be able to drive it back.

Ginetta holds your hand during the practice rounds, with professional drivers giving instruction. It also arranges for you to sit the ARDS, a practical and a theory test set by the Motor Sports Association, which grants the National B licence needed to race.

At each of the eight races, you’ll receive a signature as long as you finish. Six signatures and you earn your National A, which allows entry to Formula 3, BTCC and Pro-Am British GT races. The road to Le Mans lies ahead.

Credit: David Shepherd

Range Rover Velar review: 'Room, anyone, for an iPhone on wheels? Meet the Velar.'

Range Rover’s Velar feels classy and timeless, with pools of polished, seamless black glass that rival even Steve Job's creations.

Credit: Twisted Land Rover PR (fine for reuse)

Twisted Land Rover Defender review: 'The throttle pick-up of an F1 car, the aerodynamic profile of a washing machine'

It's several years since the discontinuation of the much-beloved Land Rover Defender, but companies such as Twisted are making sure

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: British vans, Czech shoes, and cars that leave their wheels behind as they pull away

Our columnist Jason Goodwin tells a tale of clapped-out cars, ancient vans and a Czech shoe magnate who turned the

Credit: ©Steve Ayres/Country Life

Across Scotland by motorbike: The wonders of Raasay, and the joys of Calum's Road

This summer, Country Life's Steve Ayres travelled across Scotland by motorbike. This latest instalment of his adventures sees him visit

Alfa Romeo Giulia Super review: An Italian masterpiece

Our motoring expert Charles Rangeley-Wilson will never look back after test driving this incredible car.

Credit: Jeep

Jeep Grand Cherokee review: More Vegas than Tisbury, but you can't argue with its bang-for-buck

Our motoring correspondent Charles Rangeley-Wilson tries out the Jeep Grand Cherokee and comes away impressed.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.