My favourite painting: Sue Barnes

Sue Barnes, the founder of Lavender Green Flowers, chooses a compelling portrait by Thomas Gainsborough.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

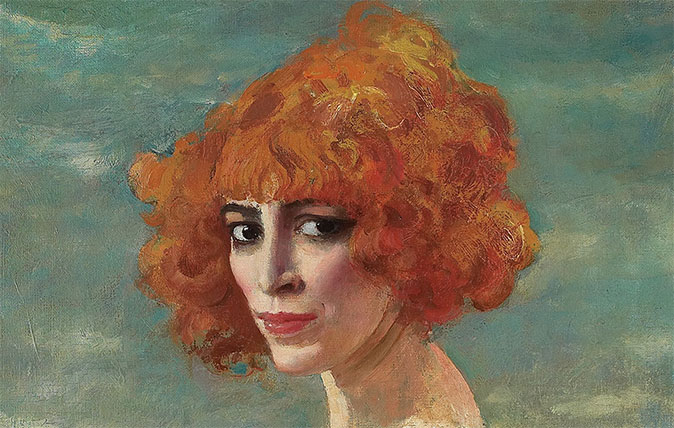

Sue Barnes on Portrait of Mrs Gainsborough by Thomas Gainsborough

'Margaret’s eyes seem to follow you around the room, because this portrait was painted by the sitter looking directly at the artist. That was incredibly rare at the time and only really possible because of the relationship between the two of them. Margaret was the illegitimate daughter of a duke and her income from his estate helped launch and sustain Gainsborough’s career. She was that rarest of creatures in the 18th century, an astute businesswoman. She was 50 when this was painted, attractive, but not an outstanding beauty. Her clothes are beautifully painted, but by no means exquisite. There is none of the materialistic paraphernalia that surround a lot of other portraits, but the way Gainsborough shows his absolute love and respect for the woman with whom he shared his life and business is priceless.'

Sue Barnes is the founder of Lavender Green Flowers.

John McEwen on Portrait of Mrs Gainsborough

Margaret Burr, illegitimate and only daughter of Henry, 3rd Duke of Beaufort, married Gainsborough in 1746, when she was 18 and expecting their first child, who died aged two.

The Duke himself had died the previous year, leaving Margaret an annuity of £200. As Gainsborough, one year her senior, was struggling to make a living as a landscape painter, his artistic preference, the annuity was a considerable help.

He was still borrowing against it in 1752, by which time the couple had had two further daughters and commissioned portraits, or ‘phizmongering’ as he derisively called it, were proving more profitable than his landscapes.

By his own admission, Margaret was his strength and stay. She had a better head for business and stood firm when he strayed and contracted venereal diseases, as well as through the long anxiety of their daughters’ mental instability. ‘I shall never be a quarter good enough for her if I mend a hundred degrees,’ he wrote.

These domestic traumas were combined with a warring relationship with the Royal Academy, despite his founding membership, and a contempt for phizmongering — his commissioners having ‘but one part worth looking at, and that is their Purse’ — a practice that, nevertheless, eventually earned him fame and a Pall Mall address.

No other 18th-century artist left so many portraits of his extended family, even to the extent of their beloved pets. They serve as proof of his affection, yet they are so often unfinished that it is suggested Margaret intervened to remind him of his professional commitments.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This portrait may have celebrated her 50th birthday. The pose derives from one traditionally suggesting chastity, thus wittily at odds with his own behaviour.

Credit: Bridgeman images

My favourite painting: Joanna Trollope

'It looks to me as if painter and subject were very well matched '

My favourite painting: David Starkey

David Starkey shares the one painting he would own, if he could

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.