'He unleashed a series of war cries, then intercepted the vole mid-air': There's nothing remotely common about the common kestrel

Known in Orkney as ‘moosie-haak’, kestrels are fierce hunters but have seriously declined and are now an amber-listed species.

Technically, this wonderful bird of prey is called the common kestrel (Falco tinnunculus), although it is probably the only raptor better known by one of several affectionate nicknames: ‘kes’, ‘kessie’ or, in Orkney, by a lovely dialect word, ‘moosie-haak’. One thing we can conclude about the official title is that it is no longer quite as appropriate as it once was. Kestrels have seriously declined and are now an amber-listed species. They are still widespread across almost all of Britain, except north-west Scotland, but the breeding numbers have tumbled. At the time of a census in the late 1980s, it was suggested that there were 50,000 pairs. The total today is 31,000.

Accounting for this decline has been challenging. Fluctuations in vole numbers, the impact of rodenticides or agricultural changes have all been mooted. Yet one factor may possibly be the rise and rise of other raptor species, which has been one of the major successes in all British environmental action in the past half century. These other British birds of prey — buzzards, goshawks and red kites — may compete with or actually directly predate kestrels.

Kestrels are known thieves, and often steal voles from barn owls.

An extraordinary revelation came at a goshawk nest in Kielder Forest, Northumberland, after that species had colonised the area: around that bird’s nest were the remains of no fewer than 20 kestrels. This raptor-on-raptor killing is technically known as ‘intraguild predation’. In effect, one larger bird of prey eliminates the competition, also providing itself or its chicks with high-quality protein.

Before we get too morally exercised about such behaviour, we should recognise that kestrels are not above a little strong-arm competition of their own. One notable development, with the rise of barn-owl numbers, is the incidence of kestrels stealing voles from the latter birds. I once encountered a short-eared owl that had made a kill, but was forced by a kestrel to climb higher and higher in spirals above the marsh. The falcon unleashed a sequence of excited kee-kee-kee war cries and eventually forced the owl, now a dot in the heavens, to release the vole. The mammal tumbled earthwards, only for it to be intercepted in dazzling fashion by the kestrel even before it reached the ground.The incident is a measure not only of the birds’ astonishing prowess on the wing, but also of their versatility as predators.

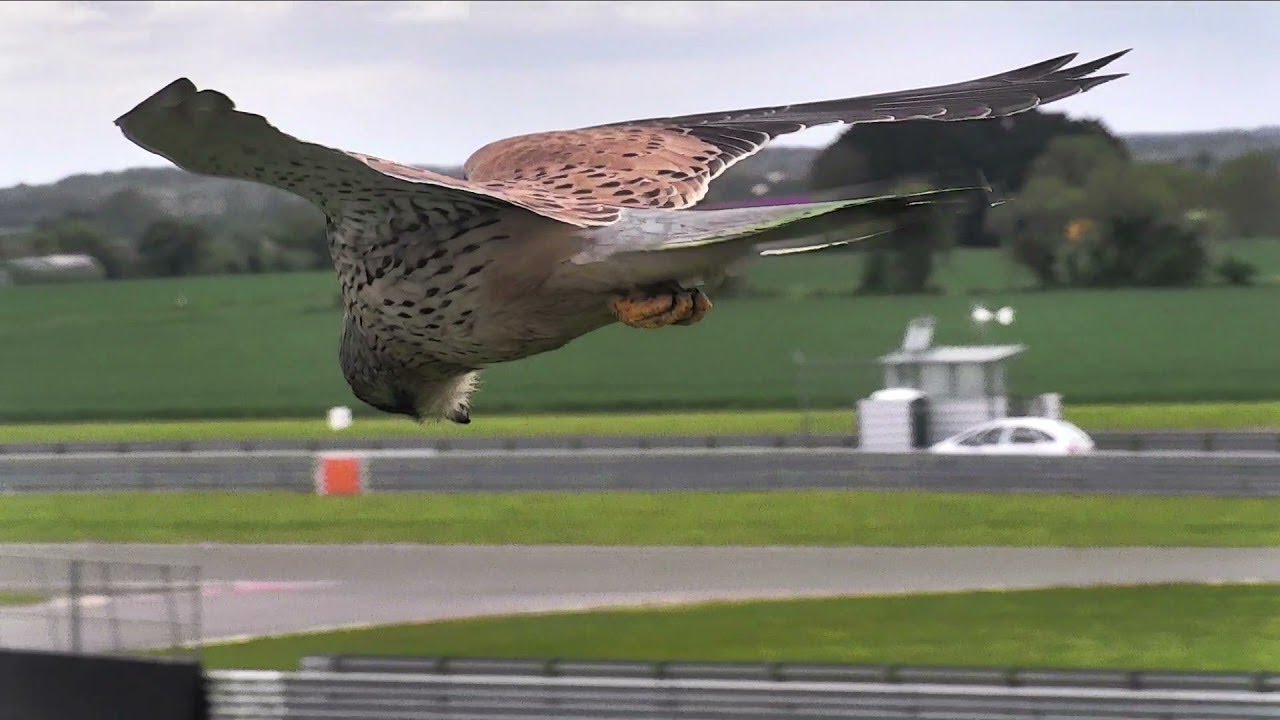

Kestrels may be famous, as the Orcadian nickname suggests, for a love of small mammals, yet they will readily take birds up to the size of a pigeon. The catching of voles, however, brings into play the kestrel’s signature manoeuvre, which once earned the birds another alternative name — the ‘windhover’. In effect, they fly into a headwind at precisely the same speed as the breeze blows them backwards. One of the few ways to appreciate truly what is happening, second by second, as a kestrel hovers is to take rapid multi-frame photographs. The images reveal two salient features: the infinitely refined and coordinated adjustments of its wings and tail, but set against the riveted-in stillness of the head.

That combination allows a bird to fix micro-movements in any small mammal with laser-like precision and then down it falls, like an arrow. The kinetics of the behaviour were explored in a poem, The Windhover, by 19th-century Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins. He had developed a characteristic style that married enormous freedom in use of vocabulary and syntax with almost chant-like rhythms. Layered into the imagery are Hopkins’s religious concerns, but he also captures in his ‘sprung verse’ both the sweeping movement and the magisterial stillness in a hovering kestrel. It is surely one of the finest bird poems in the language: 'I caught this morning morning’s minion, kingdom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding/ Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding/ High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing/ In his ecstasy!'

Kestrels may have declined across Britain, as they have across Europe, but it is still very much a bird of our towns and wider country-side. For all the changes it has undergone, it is almost the default bird of prey over the grassy slopes, to major roads and motorways. In all these quotidian places, it brings an element of grace and beauty and otherness.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Mark Cocker's latest book, ‘One Midsummer’s Day: Swifts and the Story of Life on Earth’ is out in paperback

This feature originally appeared in the July 9, 2025 issue of Country Life. Click here for more information on how to subscribe

Mark Cocker is a naturalist and multi-award-winning author of creative non-fiction. His last book, ‘One Midsummer’s Day: Swifts and the Story of Life on Earth’, is out in paperback. A new book entitled 'The Nature of Seeing' will be published next year by Jonathan Cape.