The terrible truth about the cuckoo, and the 'monstrous outrages' it perpetrates on its foster parents and siblings

The cuckoo is a bird whose behaviour is so horrendous — when judged by human standards, at any rate — that it wasn't until the advent of wildlife film that ornithologists finally acknowledged and accepted the depths that it plunges. Jack Watkins explains.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The call of the male cuckoo, usually heard in April — but sometimes earlier — is firmly associated with the arrival of the British spring. So much so that, into the middle of the 20th century, The Times published first cuckoo letters from readers, following the birds’ arrival from their African wintering grounds.

The sound may be as close as you get to the bird, as cuckoos are secretive. However, if you do spot one, you may be surprised at its size. In the years before migration was an accepted fact, some thought their absence for most of the year could be explained by an ability to change into a hawk and back again. In fact, with their long wings and tail, as well as black barring across the chest, cuckoos can, indeed, look like sparrowhawks.

Although the evocative cu-coo, heard in the distance on a gentle spring day, is one of Nature’s great delights, that’s about as charming as this bird gets. In truth, if the cuckoo were human, it would be considered a rogue, a fraudster and, not to put too fine a point on it, a cheat.

The only British bird not to rear its own young, the common cuckoo makes no nest of its own, instead using other birds to handle incubation and feeding duties. Favoured host species — or dupes — include meadow pipits, robins, dunnocks, reed warblers, pied wagtails and willow warblers. The targeted hen birds proceed to hatch the egg and rear the cuckoo chick, even after the hatchling has ejected all the other, ‘legitimate’ eggs or chicks from the nest, sending them to their deaths.

The foster parents ignore this outrage and put all their energies into feeding the young cuckoo (which will never see its real mother), even as it grows to five times their size. As the Fool put it in King Lear (Act 1, Scene IV): ‘The hedge-sparrow fed the cuckoo so long, that it’s had it head bit off by it young.’

For years, naturalists struggled to accept that such behaviour existed. The Rev Gilbert White called it ‘a monstrous outrage on maternal affection, one of the first great dictates of Nature’. Others tried hard to find mitigating explanations. One of White’s correspondents, Daines Barrington, advanced the comforting thought that the mother cuckoo probably carried on feeding its young, visiting the foster parents’ nest.

Even when Edward Jenner, better known for his pioneering work on vaccination, produced a paper, in 1787, describing the process by which the young cuckoo tumbled the eggs and chicks out of the nest and told of watching the foster parents feeding the cuckoo, it was initially rejected by the Council of the Royal Society.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

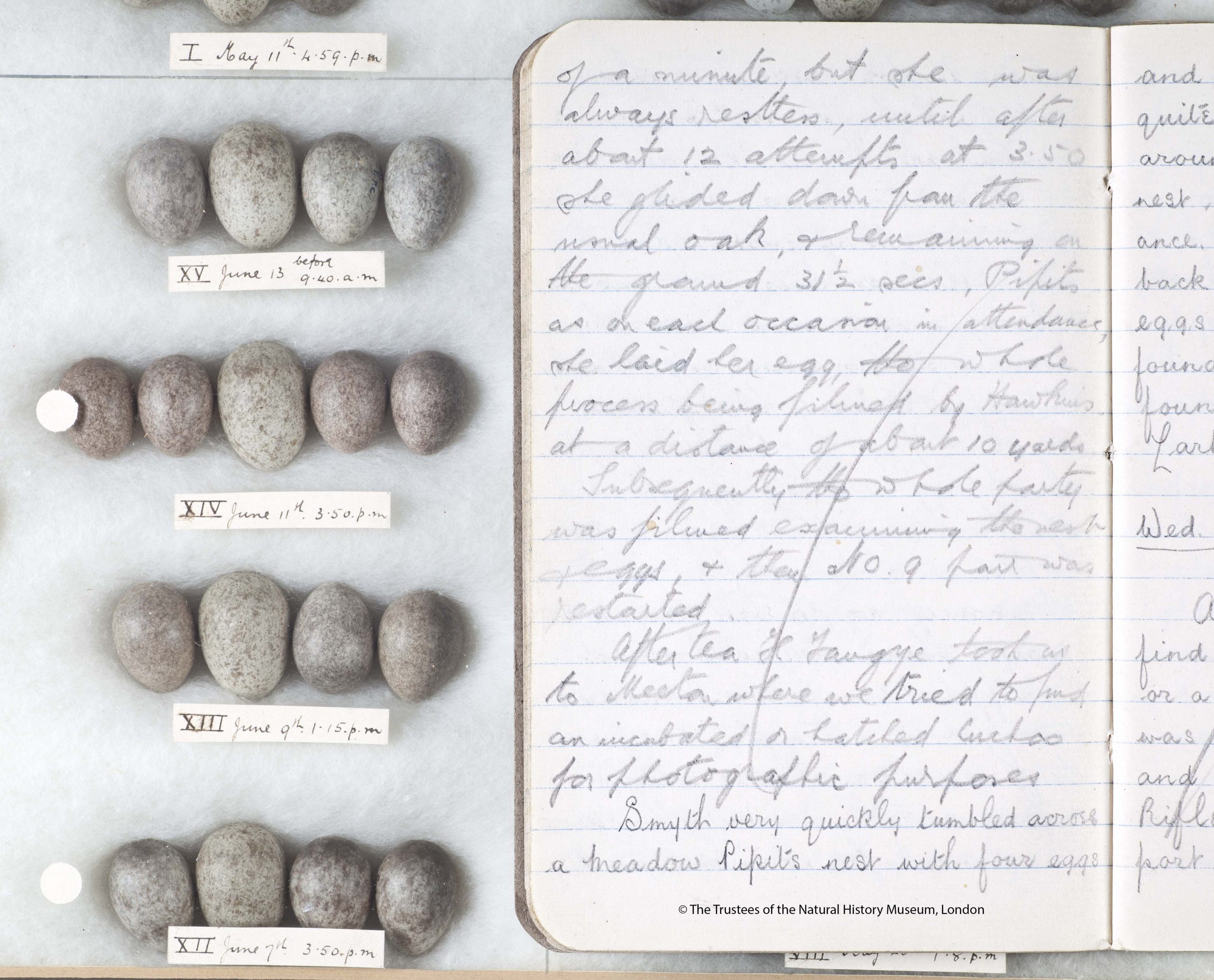

Into the early 20th century, the parasitic behaviour of the cuckoo was still the subject of wild speculation, until Edgar Chance, an eccentric businessman from the Midlands, took it upon himself to lift the veil of supposition. In doing so, he effectively became the first ornithologist to devote his studies to a single species.

Chance’s chosen place of observation was a 52-acre, gorse-covered common known as Pound Green in Worcestershire. His aim was to show that the cuckoo actually laid her egg in the nest of the dupe species, rather than, as many believed, laying it on the ground and using her bill to lift and place it into the nest. His short silent film The Cuckoo’s Secret, which caused a stir on its first public screening at the New Gallery Kinema on London’s Regent’s Street in 1922, was one of the first wildlife documentaries ever made.

https://youtu.be/HxFO6OaDgeQ

The language used in the subtitles was emotive, with the female cuckoo described as ‘the feathered wrecker of homes’. The newsreel footage, by pioneering bird cameraman Oliver Pike, was the result of hours of patient observation by the plus-four-clad Chance across several summers, from 1918 onwards.

Absorbed by his project, Chance even slept out on the common — by being there at dawn, he hoped to catch the cuckoo in the act of laying her egg in the nest of a meadow pipit. As it happened, she fooled even him, for he was to find that the event actually occurred in the afternoon.

As well as showing the mother cuckoo darting into the pipit’s nest to lay the egg in a matter of seconds, the film revealed the cuckoo fledgling in the act of tumbling his meadow-pipit mates out of the nest. One observer refused to believe his eyes, accusing Chance of placing the egg in the nest himself; another called the film ‘a glimpse of the appalling cruelties of the struggle for existence, the survival of the fittest’.

'When Chance died in 1955, his passing was barely acknowledged within the ornithological community'

Chance followed the film with a book of the same name, which included Pike’s photographs. It was later updated and expanded in The Truth About the Cuckoo, published in 1940. By then, however, Chance had fallen from grace.

Egg collecting had played a major role in the advancement of our knowledge of birds and he was an inveterate oologist. From the 1890s onwards, the conservation movement had become increasingly vocal about the impact of egg collecting on population numbers and protective legislation had been stepped up.

In 1926, Chance was prosecuted under the Wild Birds Protection Act of 1894, for aiding and abetting in the taking of the eggs of another secretive bird, the crossbill. He claimed to be collecting for scientific purposes, for Reading Museum, but was fined and forced to resign from the British Ornithologists’ Union. When he died in 1955, his passing was barely acknowledged within the ornithological community.

Despite this, Chance’s work is regularly referenced today, and his vast egg collection widely consulted. In 2015, Nick Davies’s Cuckoo: Cheating by Nature contained a passage in which he described revisiting Pound Green and sitting ‘alone on a silent common, saluting the memory of Edgar Chance’. Prof Davies imagined Chance working on the common in his tweed suit and tie and suggested that his meticulous observations of the cuckoo’s secret ‘must rank as one of the greatest feats in field ornithology’.

For naturalists, a cuckoo chick’s behaviour will never lose its ability to astonish. Prof Davies says that every time he watches it, whether on screen or at Wicken Fen, where he has been studying the birds for decades, he’s still amazed — he has even seen the nest evictions taking place when the host parent is sitting in the nest.

Not all the mysteries of the creature have been fully explained. Given that young cuckoos aren’t reared by their true parents, which begin migrating back towards Africa in July — when their offspring are still being reared by the foster parents — the fledglings must find their way out of this country to their ancestral wintering grounds alone. They will receive no help from foster parents such as dunnocks, robins and most meadow pipits, which remain in this country all year, and if reared by migrant species, these would be travelling to different wintering areas. Adrift from its siblings, which will have been raised in different nests, the young cuckoo has to navigate its way across as much as 5,000 miles in extreme isolation.

In Chance’s day, the cuckoo was, as he wrote in The Cuckoo’s Secret, ‘well distributed and met amidst all the varied scenery which the country can show’. Since then, we’ve lost more than half the population, the steepest decline coming in the past 20 years. Considering whether much of this may be explained by difficulties encountered on their taxing migratory routes, the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) has been satellite-tracking the birds to try to find answers.

Chance, who had a populist touch, called one of the cuckoos he studied Mary Pickford, after the film heroine of his time. He would surely have loved the fact that the BTO has given each of the tagged fliers names — ranging from Raymond to Tennyson — and in his wish to ‘support deductions with evidence’, he would surely have been an avid online follower of their progress.

The BTO’s Cuckoo Tracking Project can be followed at www.bto.org/our-science/projects/cuckoo-tracking-project

In Focus: The mesmerising automaton created by the man who made Chitty Chitty Bang Bang fly

The 'finest work' by Rowland Emett, the man who designed the machines for Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, goes on display

Jack Watkins has written on conservation and Nature for The Independent, The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph. He also writes about lost London, history, ghosts — and on early rock 'n' roll, soul and the neglected art of crooning for various music magazines