The Woodland Trust at 50: How a car nut with a yellow Ferrari helped save the trees of Britain

The Woodland Trust was set up as a Nature-conservation charity specifically concerned with trees. Clive Aslet visits its south Devon birthplace of 50 years ago and remembers its far-sighted and altruistic founder, Ken Wood.

The leaf litter and pine needles form a deep, springy mattress on the forest floor. Fallen boughs and the remains of tree stumps, rotting back into the ground, are as soft as sponges. Few people find their way to this mossy pocket of immemorial woodland on the edge of Dartmoor in Devon. Trees are multi-stemmed, hollow, tortuous in form, their branches green and woolly from lichens.

Hall Plantation on the Hall Farm estate, I am told by David Rickwood, site manager for the Woodland Trust, has all the characteristics of a temperate or Atlantic rainforest, a habitat formed by the constant presence of moisture — in this case, rolling in from the sea — and mild temperatures: ‘It supports an ecosystem that is rarer than the Amazonian rainforest, if less obviously threatened.’

A beech, shaped like an octopus, has crashed to the ground, felled by the plate-like bracket fungus that weakened its trunk. One limb still puts forth leaves, as it obstinately clings to life. This is a weird landscape, festooned with the hairy grey strands of Usnea articulata, similar to the Spanish moss that hangs from the live oaks of America’s southern states (it was thought to resemble the Conquistadores’ beards), but which in Devon is known, less romantically, as string-of-sausages. At least a dozen of Britain’s 17 species of bat live here, diving into the crevices of senescent trees. The rotting timber is a Holiday Inn for invertebrates.

In the Middle Ages, this area supported four farms, the field patterns of which can still be seen. The name ‘Plantation’ suggests a more recent origin and probably dates from the time of the Napoleonic Wars, to judge from the dry-stone wall that surrounds the wood, although the early-19th-century plantings may have overlaid pre-existing woodland.

A tumble of stones is said to be the remains of a Georgian pleasure house that belonged to Elizabeth Chudleigh, the bigamous Duchess of Kingston. My visit, however, is being made to remember another owner: Ken Watkins, universally known as KW, who founded the Woodland Trust 50 years ago in 1972.

Born in Bromley, Kent, KW had been living in Devon since the 1920s. Initially an agricultural apprentice, he and his brother went on to buy neighbouring farms at Harford, just under the moor, which they worked together, before founding Western Farm Machinery, a business selling tractors. With the Second World War and the intensification of agriculture that came after it, the company did well; KW could indulge his love of racing cars.

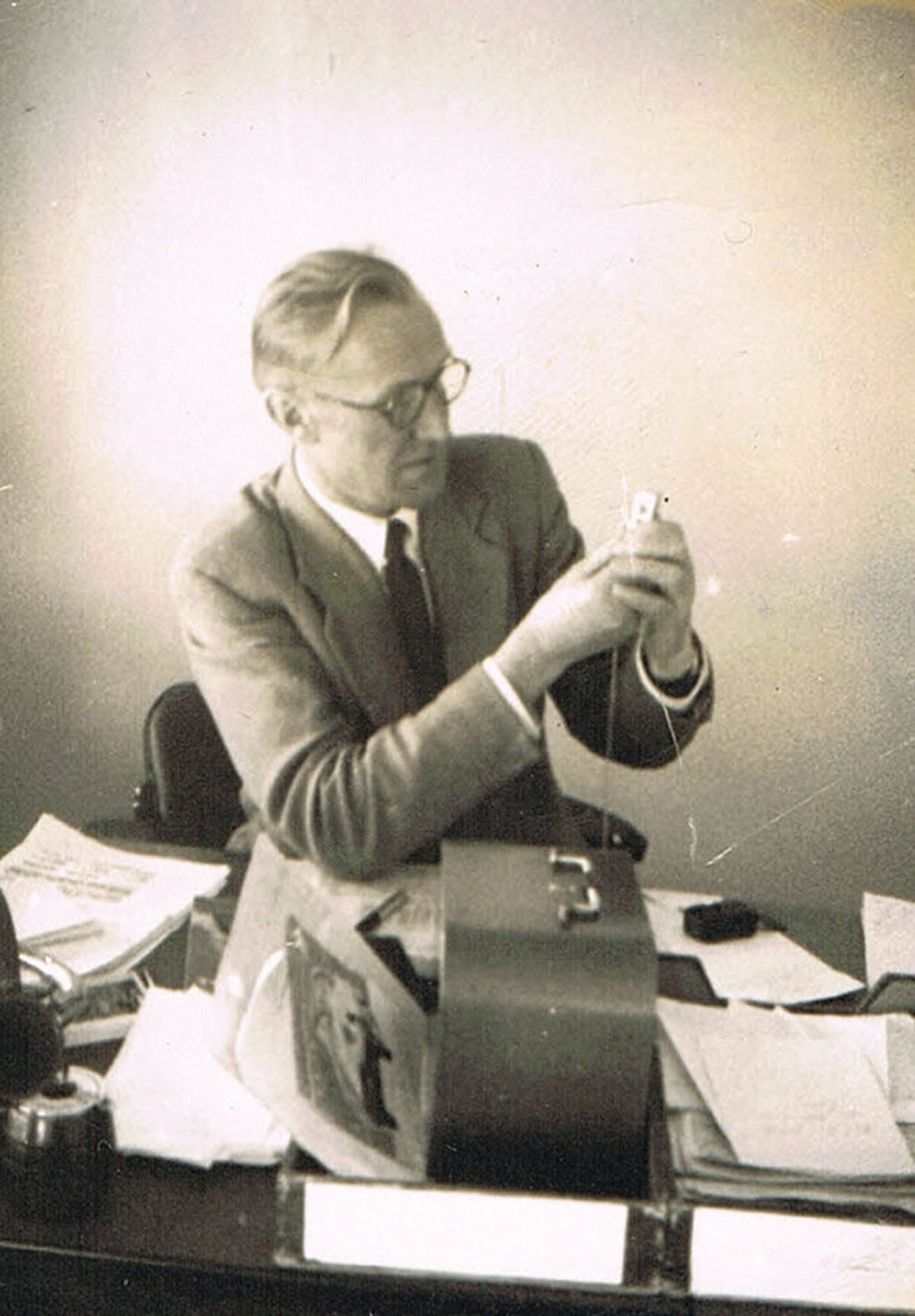

However, this shy and modest, if stubborn man was also acutely aware of the damage that the application of industrial techniques to farming inflicted on the countryside amid which he lived. When the Devon Wildlife (then Naturalists) Trust was founded in 1962, he served as honorary secretary. However, the focus on estuaries and open land meant that, in KW’s view, his colleagues were not digging deep enough to buy enough of the small woods, copses and spinneys that characterised the British landscape. Some were being grubbed up, others being replanted with fast-growing conifers. Behind the wheel of a yellow Ferrari, KW scouted out suitable candidates for acquisition. When he and his brother sold their company and retired from business, he could create a body dedicated to his beloved woods.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Half a century later, the Woodland Trust cares for more than 1,000 woods across Britain, restores depleted woodland habitats, campaigns for woods to be protected (it is currently petitioning on its website for stronger legal protection for old trees) and plants more than 50 million trees. However, from a policy of buying woods to protect them, the charity has come to realise that sympathetic landowners under management agreements can yield results on a larger scale, by making precious funds go further, than purchase alone would do.

Ancient trees — defined as more than 400 years old in the case of oaks — are a special object of affection. With its relatively settled history, Britain has a large number of these arboreal Methuselahs, gouty, fat, hollow and stag-headed; on the Continent, roaming armies found their hollow trunks easy to cut down for firewood. The trust has been mapping these remarkable and vulnerable lifeforms, wherever they are to be found across the UK.

In contrast with Britain’s large number of ancient trees, however, is the state of our woodland cover, which is woeful by Continental standards: a mere 13% of the landmass, compared with 33% in Germany. Yet the news is not all bad. According to the Woodland Trust’s survey The State of the UK’s Woods and Trees 2021, which was the first report of its kind, the amount of woodland across Britain is about double what it was 100 years ago. One problem is that most of the new trees are not natives and the threats have multiplied — think of this summer’s high temperatures and drought, not to mention the tsunami of imported diseases.

Irreplaceable ancient woodland has fared particularly badly, which is why the Woodland Trust is campaigning for it to be protected from development and other threats, such as HS2. Once destroyed, ancient woodland cannot be re-created elsewhere, because of the complex biodiversity that has built up over the centuries. Happily, however, it is possible for ancient woods that have been planted with inappropriate commercial species to be loved back into a flourishing condition, with sensitive management.

In Hall Plantation, Mr Rickwood stoops to grasp the top of a hemlock seedling, which is easily pulled out of the mulch amid which it is growing. Hemlock is particularly unwelcome in the wood, being a vector for Phytophthora pluvialis, an even more devastating form of phytophthora than that which attacks larch. This seedling is a child of the conifers planted here after the Second World War, as part of the effort to meet the nation’s strategic need for timber. Now, the conifers are seen as a conservation disaster, which could crowd out native species.

They have to be felled — but that is not as easy as you might think. Clearing them would release myriad seeds, ready to germinate in the newly available light. They are, therefore, cut down in small groups and, as it is impossible to get a modern tractor across the old bridge over the River Eden, which a warning notice proclaims to be 7ft wide, a portable sawmill is set up to mill the trunks.

This yields a further gain for conservation: the resulting planks are used to block up the drainage ditches that were dug in the 1960s and 1970s to convert peatland to more profitable uses — a futile exercise that was, furthermore, damaging to the environment, destroyed rare habitat and released carbon into the atmosphere; rewetted peatland forms a carbon sink.

Half an hour’s drive south of Hall Plantation are the five blocks of woodland that comprise the Avon Valley Woods, near Modbury in south Devon. Among them is Bedlime Wood, the first plot to have been bought by the trust. Difficult to access, it is left to itself, as KW intended, to the benefit of its wildlife as well as the plants and trees. The other woods have been developed by the trust and linked by paths, a move appreciated during lockdown. Trees are famously long-lived and will not reach maturity for decades, so the Woodland Trust is about nothing if not continuity. In a changing world, it is a celebration of hope.

Woodland Trust membership costs from £4 a month. To join or to vote for your favourite tree, visit www.woodlandtrust.org.uk

Beech trees: A complete guide

The beech tree is one of the finest sights in British woodland: effortlessly tall and graceful, offering year-round colour in

Credit: Alamy

10 perfect photographs that will remind you why you love Autumn

Country Life celebrates some of the most evocative images of autumn.

The cold snap and falling leaves in Britain have actually been a 'false autumn'

The leaves, acorns, nuts and berries that have been falling across the country aren't just reacting to a cold snap