Curious Questions: What is a jubilee?

The celebration of HM's Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee is imminent — but what is a jubilee, and where does this strange word come from? Martin Fone investigates.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Until this year fifteen monarchs around the world had reigned for at least seventy years, the grand-père of them all being Louis XIV whose 72 years and 110 days on the French throne is the longest recorded of any monarch of a sovereign country. On February 6, 2022, Queen Elizabeth II became the sixteenth. A series of celebrations are being planned this year across the country and the Commonwealth to mark what is known as her Platinum Jubilee year.

The word — through repetition everywhere — has become familiar, almost comforting as it reminds us of those things which endure. But what is a jubilee?

Jubilee years were part of the cycle of days and years in Judaic tradition. Seven days made up a week, the seventh day being the Sabbath, a day dedicated to rest and worship. There were seven years in a cycle; the seventh year, the Sabbath year, was when the land lay fallow. And according to the Book of Leviticus (25:10), after forty-nine years, a cycle of seven weeks of seven years, ‘you shall consecrate the fiftieth year and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you.’

The jubilee year was a way of resetting the dial. All leased or mortgaged lands were to be returned to their original owners and all slaves and bonded labourers were to be freed. There were carefully crafted provisions to mitigate the economic mayhem that these strictures may have caused (Leviticus 25:15-16), but the underlying principle was that everyone should be free to enjoy the fruits of their own labour.

A blast on a shofar — a rudimentary trumpet made from a ram’s horn — marked the start of the Jubilee year. The Hebrew word for ram was ‘yobhel’, which may be the origin of our word ‘jubilee’; although it is just as likely to have been derived from the Latin verb ‘jubilare’, to shout out joyfully or to celebrate.

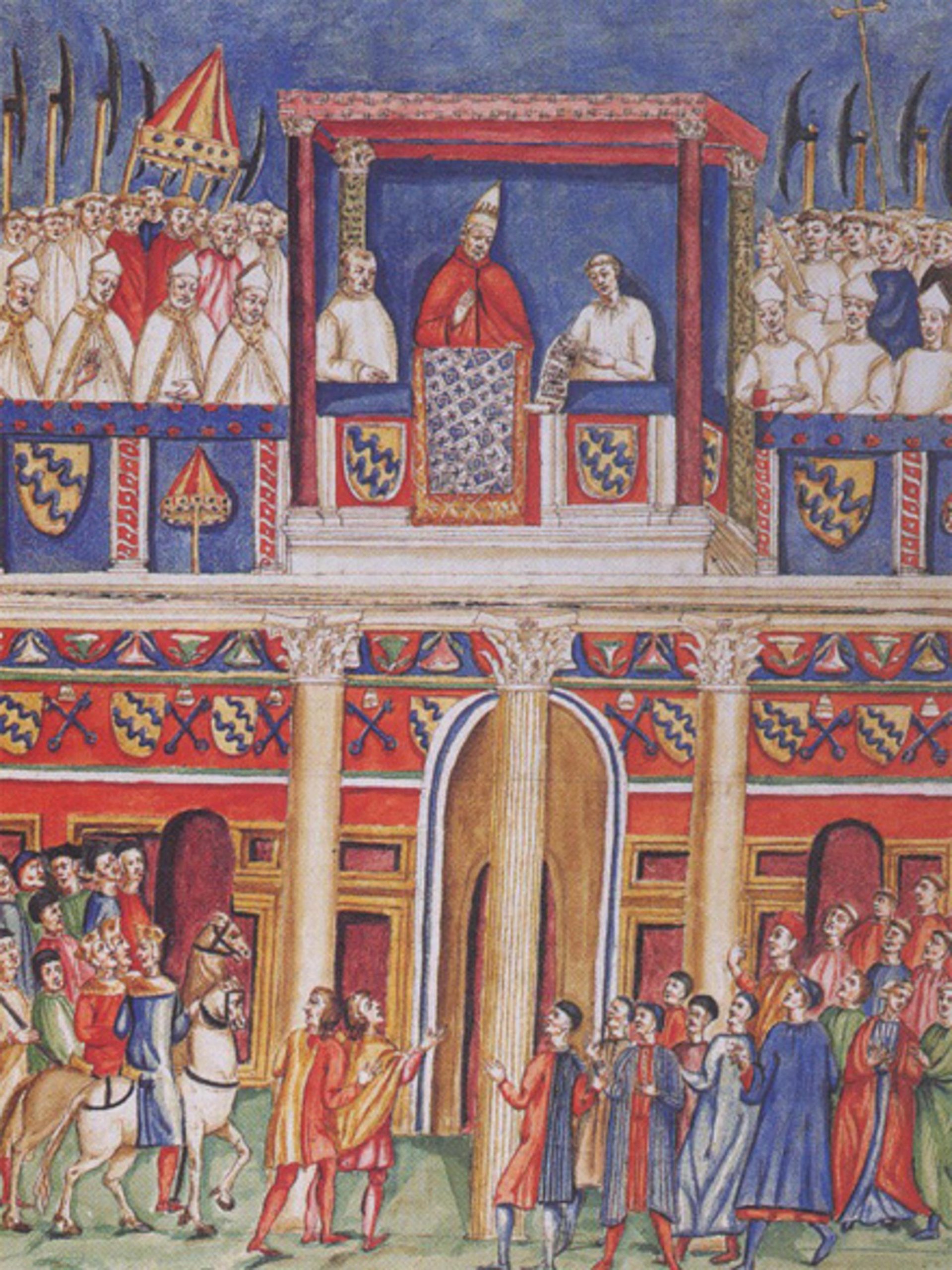

Jubilee years were introduced to the Christian world by Pope Boniface VIII in a Papal Bull, Antiquorum fida relatio, published on February 22, 1300. He promised that anyone who made a full confession and made a pilgrimage to Rome would be absolved of all sins. Once in Rome they were required to visit the basilicas St Peter and St Paul for fifteen consecutive days; or, if they were Roman citizens, for thirty.

Boniface wasn't merely seeking to encourage pilgrims, incidentally. He introduced jubilee years to the west in response to a period of pandemic, poverty and war in Europe. There is a curious aptness that, at least in England, 2022 should be a jubilee year too.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Pilgrims flocked to Rome, the chronicler Giovanni Villani observing that it was ‘the most marvellous thing that was ever seen, for throughout the year, without a break, there were in Rome, besides the inhabitants of the city, 200,000 pilgrims…and all was well ordered, and without tumult’. The Papal coffers received a welcome boost, and the jubilee was declared a success, so much so that Pope Clement VI overturned Boniface’s original intention of holding one every hundred years by organising another, in 1350.

In the 1380s Pope Urban VI decided that the jubilee years should reflect the duration of Christ’s earthly life and be held every thirty-three years, but by the mid-15th century the frequency had become once every twenty-five years as it is today — thus, for Catholics, 2025 is the next jubilee year. From the year 1500 onwards, pilgrims entered the principal basilicas through special doors, known as ‘Holy Doors’, and temporary walls built behind them were ceremonially broken down by the Pope to mark the beginning of the year.

Royal jubilees were much more infrequent, and originally marked fifty years of a monarch’s reign. The first English monarch to reach that landmark was Henry III, but whether he was inclined to celebrate — in 1266 he was in the middle of fighting a civil war — is doubtful. There are no records to show how Edward III or James VI of Scotland and James I of England celebrated their fifty years on the English and Scottish thrones respectively.

The jubilee of George III was celebrated, though. Curiously, the date chosen for the celebrations, October 25, 1809, was the forty ninth anniversary of his reign, although, technically, the start of his fiftieth year. George’s ability to participate was limited by poor health and failing eyesight but the occasion was marked by a service at Windsor and a fete at Frogmore, which, according to John Stockdale’s The New Annual Register, ‘in point of taste, splendour, and brilliancy has on no occasion been excelled.’

At 9:30 in the evening the gates were thrown open to the nobility and gentry who had tickets of admission and the Royal family stayed until the early hours, enjoying the sight of Britannia being transported in a chariot drawn by seahorses and an impressive display of fireworks. In London, meanwhile, the Lord Mayor led a procession to St Paul’s Cathedral for a service of Thanksgiving, before finishing the day off with a dinner at the Mansion House.

Celebrations were held throughout the land. Roast ox and sheep, and plum puddings were eaten, strong ale quaffed, sermons preached, bells rang out, flags waved, God Save the King sung, and food and alms distributed to the poor. In Abingdon cakes were thrown from the top of the Market House, while in Blisworth in Northamptonshire, the ‘respectable’ inhabitants gathered at the Grafton Arms for a supper where ‘harmony and convivial mirth crowned the festivities of the day’. Debts were cancelled and prisoners released, including ‘all persons confined for military offences’ and in Reading some Danish prisoners of war.

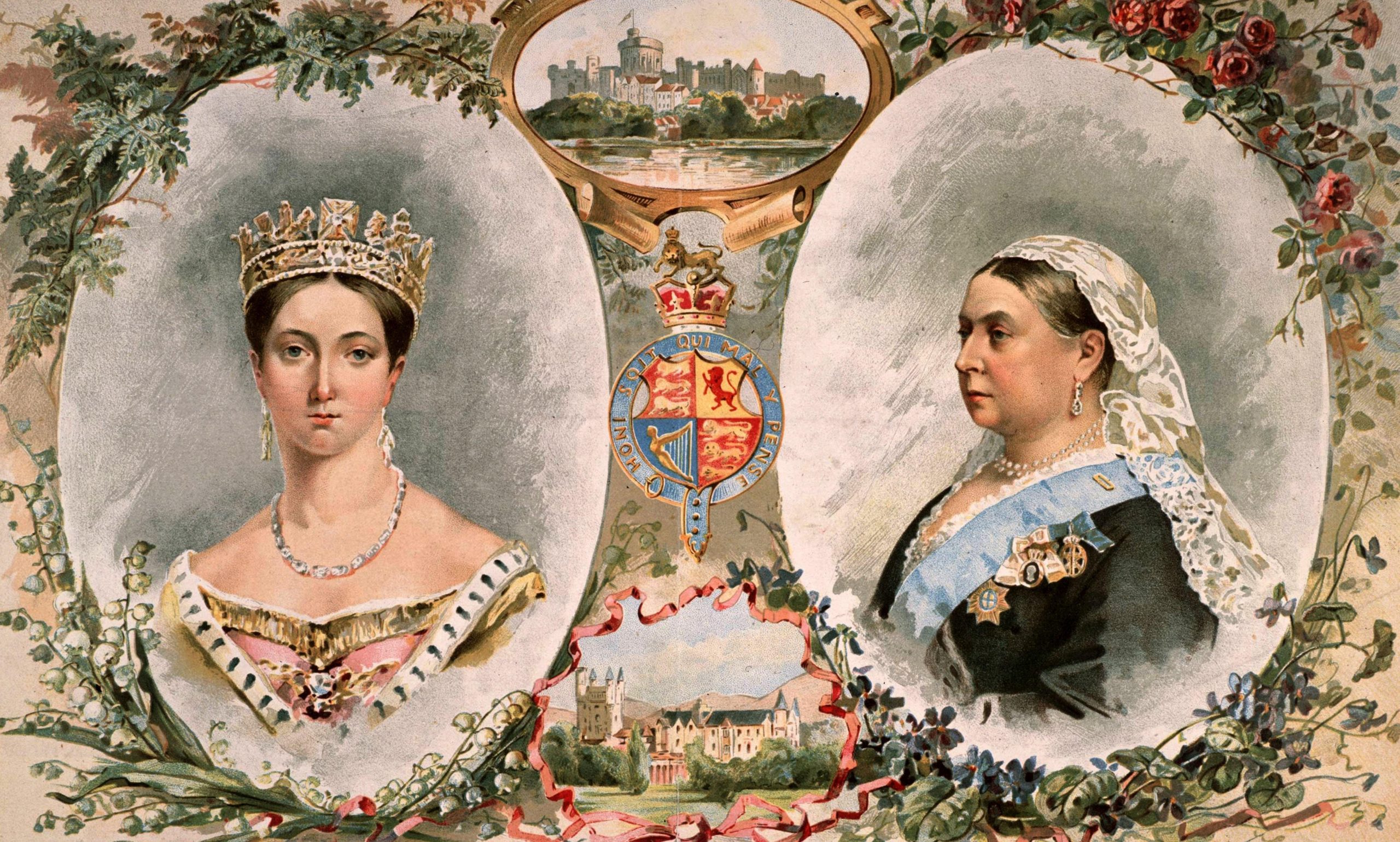

One Oxfordshire village reportedly insisted that any child born there during the jubilee year be called Jubilee George or Jubilee Charlotte. For those looking for more conventional souvenirs of the event, there were souvenir medals bearing the portraits of George and his queen, Charlotte, and commemorative plaques, jugs, mugs, and bowls to buy. By the time Queen Victoria celebrated her Golden Jubilee on June 21, 1887, the range of souvenirs had been extended to include commemorative coins and stamps and a range of bric-a-brac such as teapots, butter dishes, mirrors, handkerchiefs, woven silk pictures, wallpaper, and pipes. It’s good to know that the market in pointless tat that accompanies these occasions is as much a part of the celebration as it ever was.

One of the highlights of Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee on June 22, 1897, was her stately procession through the streets of the West End, the City, and some of the poorer quarters of London, accompanied by many of the crowned heads of Europe and princes, maharajahs, and chiefs from around the world. Cutting edge technology allowed the Queen to send a telegraphic message to all quarters of the globe; ‘From my heart I thank my beloved people. May God bless them!’

There were two royal jubilees in the twentieth century, both marking the monarch’s twenty-fifth anniversary on the throne, and there have already been three in the 21st century, testament to the longevity of Queen Elizabeth. Her Platinum Jubilee celebrations are unlikely to match the Heath Robinsonish way in which her grandfather, George V, lit the bonfires to mark his Silver Jubilee on May 6, 1935. At 9.55pm he pressed a button in his study, activating a relay circuit connected to a telephone box in Hyde Park, which blew a fuse inserted in a nearby bonfire, thus setting off the chain of fires.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.