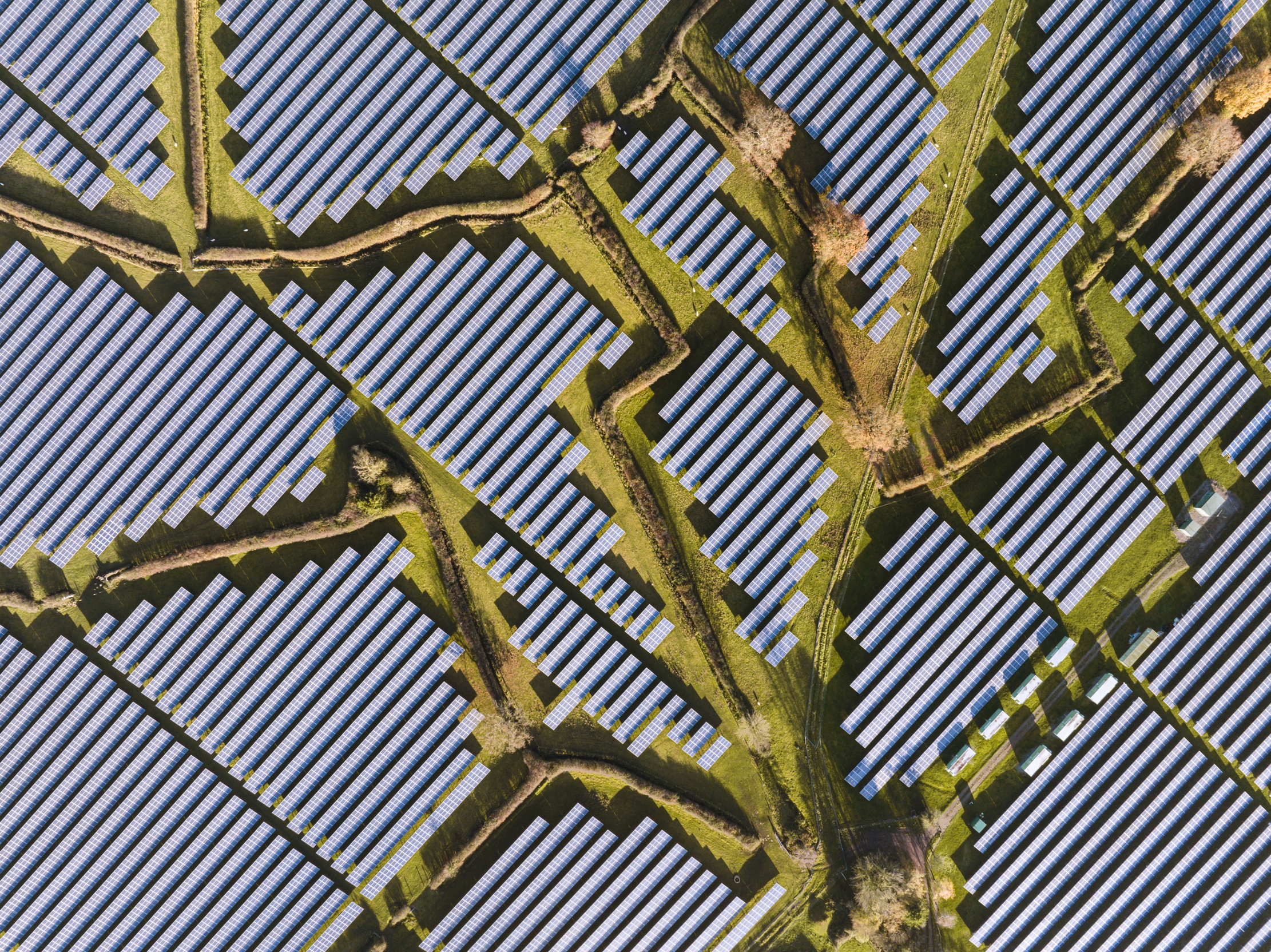

'Empires of the sun': in Britain's solar revolution, who will win the battle between food security and food production?

As more solar farms are built and approved, critics worry about the impact on food production and whether 1st generation panels are being properly disposed of.

Solar power is a growth industry, critical to the Government’s pursuit of net-zero emissions and mired in controversy. Britain’s largest solar farm, the 220-acre Shotwick Park in Flintshire, is about to be dwarfed by super schemes already in the pipeline. In Nottinghamshire, 6,920 acres of agricultural land have been earmarked for the Great North Road solar park, together with 3,700 acres for the neighbouring One Earth project and 13 smaller solar farms in an area compared to the Klondike Gold Rush.

Last month, protestors marched on Westminster to oppose Oxfordshire’s Botley West solar scheme on land owned by the Duke of Marlborough’s Blenheim estate (3,440 acres) and the Lime Down project in Wiltshire on the Duke of Beaufort’s land near Badminton (2,000 acres). The latter has been described as a ‘carbuncle’ by North Wiltshire MP James Gray, who complains that the county already hosts eight of the 10 largest solar parks in England.

It is true that installations with a capacity of at least 1MW (one megawatt) are concentrated in the South, where there is good connectivity to the National Grid. Even so, ‘Must try harder’ is on the report card for the Department of Energy & Climate Change if the Government is to reach its stated target of 70GW (gigawatts) of solar-power generation by 2035 — five times the current output.

Government guidelines say solar farms should ideally be on brownfield sites (see box below). Yet Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s pledge to protect valuable agricultural land from solar panels is challenged as megaparks are rated as ‘critical national priority’ by his Government. The UK Solar Alliance opposes large-scale greenfield developments and publishes a list of schemes both under consideration and commissioned.

'For many, this is a battle between food security and carbon reduction'

For many, this is a battle between food security and carbon reduction. Opponents of the 2,500-acre Sunnica Energy Farm on the Cambridgeshire/Suffolk border claim that half the earmarked land is graded ‘best and most versatile (BMV)’, producing 32,000 tons of food with irrigation and water storage, and would be lost ‘forever’. During the five-year campaign against it, a decision by the Secretary of State has been repeatedly deferred; a new date has been set for June 20.

Developers insist that land need not be taken out of production. Smart websites show sheep grazing between banks of panels or snoozing in their shade and solar farms sown with wildflowers to encourage pollinators. According to the West Oxfordshire Green Party, much of the land proposed for the Botley West scheme has been intensively farmed: ‘It is not unreasonable to claim that biodiversity would be improved… by a switch to solar panels and the end of ploughing, fertilisers and pesticides.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The solar bonanza offers economic benefits to farmers struggling to keep their heads above water, although not to tenant farmers, who lose out as their landlords take the developer’s shilling. Annual index-linked rents vary between £850 and £1,100 per acre for a lease term of at least 35 years, with extra payment for battery storage. Landowners considering leasing land for solar should make sure the developer is responsible for decommissioning the site at the end of the term.

What then happens to the panels and the rest of the infrastructure? Recycling of photo-voltaic panels is in its infancy because the first generation is only now about to come to the end of its life. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, only 10% are currently recycled, with the remainder going into landfill. ‘The economics of solar,’ warns the Harvard Business Review, ‘so bright seeming… would darken quickly as the industry sinks under the weight of its own trash.’

Credit: John F Scott/Getty Images

Getting a wiggle on: How 're-wiggling' our rivers can save our countryside

For more than a century, rivers have been straightened. Now, however, meandering projects are going on across the country to

Everything you could ever want to know about Badminton, 'the most important and most typically English' eventing competition in the world

In the latest edition of The Legacy, we look at the 10th Duke of Beaufort who, so disgusted at Britain's

A century of Royal Photography is going on show at Buckingham Palace, from Cecil Beaton to Annie Leibovitz

The Royal Collection Trust's summer exhibition at Buckingham Palace brings together some of the most wonderful royal portraits ever taken.

The mystery of the hedge: How an exhibition on these living walls seeks to explain our fascination with their place in the landscape

Gareth Gardner wondered if he was the only photographer interested in hedges. Now he has the answer.

Jane Wheatley is a former staff editor and writer at The Times. She contributes to Country Life and The Sydney Morning Herald among other publications.