'There are some things that never will be reproduced if the world lives a million years': What it was like to be alive at the end of the First World War

They cheered, they cried, they laughed, they danced in the streets. Almost 100 years to the day since it was signed, Clive Aslet reflects on what the Armistice meant for our nation, both then and now.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the late summer of 1914, Ethel Bilborough, an amateur artist married to an insurance manager, bought a small Union Flag. Just as the rest of the country did, she waved it enthusiastically as the British Expeditionary Force marched off to war. When not being waved, it was put in her window.

However, as the months dragged on, such exhibitions seemed inappropriate. It was hung on her chimneypiece, only to be taken down when there was something worth cheering about.

That moment came on November 11, 1918. ‘Today has been a truly wonderful day,’ she wrote in her diary, ‘and I’m glad I was alive to see it!’

Ethel had spent the morning attempting to write a letter, which was difficult in the atmosphere of febrile expectation. Then ‘suddenly the air was rent by a tremendous BANG!’. Her first instinct was that a Zeppelin raid was taking place, but ‘when another great explosion shook the windows, and the hooters at Woolwich began to scream like things demented, and the guns started frantically firing all round us like an almighty fugue, I knew that this was no raid, but that the signing of the armistice had been accomplished!’.

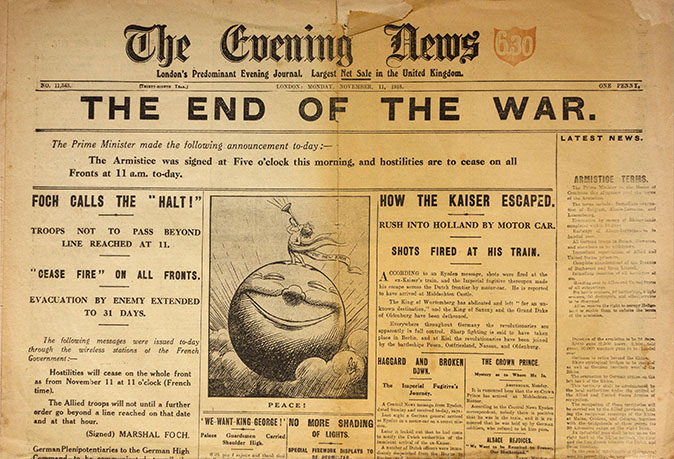

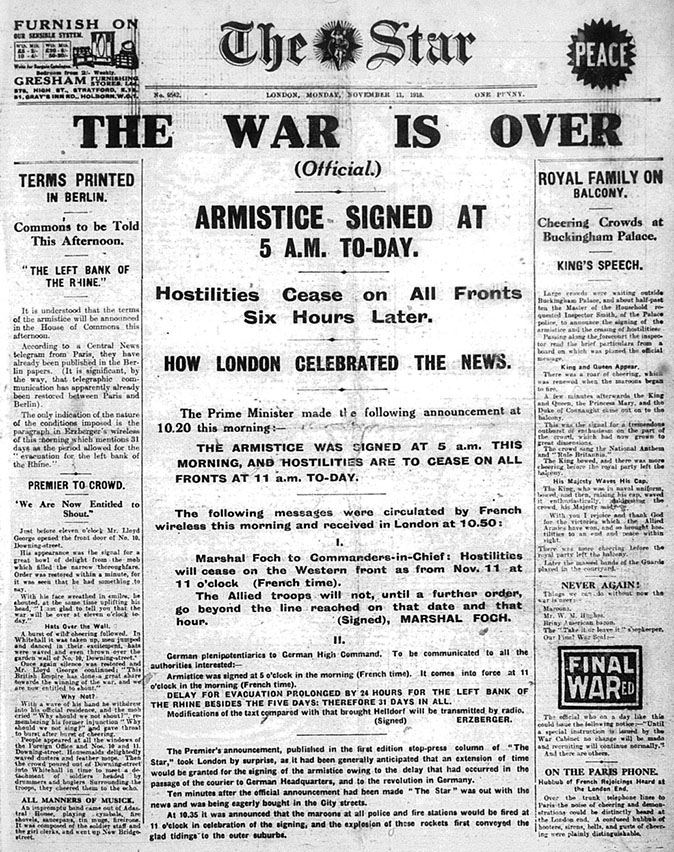

Other signals left no doubt that ‘the greatest war in history was over’. London went mad.

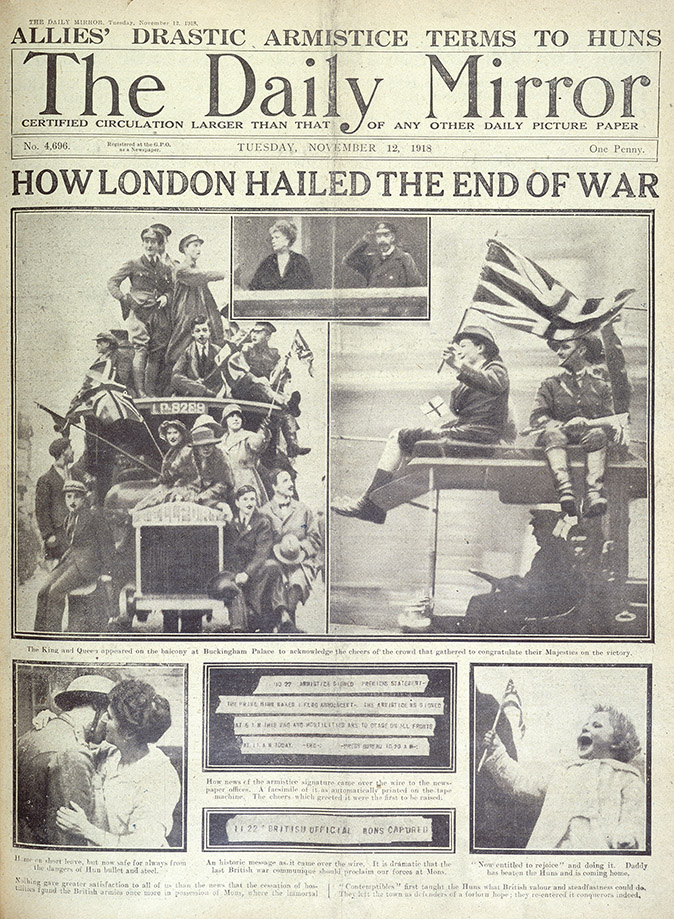

It became, in the words of The Illustrated London News, ‘the scene of an improvised carnival’. Long-repressed feelings erupted. A nation that ‘had never indulged in jubilations over incidental successes, found expression at last in the hour of final triumph’. Buses were mobbed, motorcars commandeered, cartoon images of the Kaiser mocked.

Thousands collected in front of the gates of Buckingham Palace, calling for the King. Queen Mary, usually unbending, went so far as to wave a flag. MPs left Parliament to give thanks in St Margaret’s Church.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

By evening, the capital, as other cities did, had thrown British reserve to the winds.

Robert Graves later remembered the scenes in his poem Armistice Day, 1918:

And there’s flappers gone drunk and indecent

Their skirts kilted up to the thigh,

The constables lifting no hand in reproof

And the chaplain averting his eye.

The outpouring of emotion wasn’t entirely unprecedented ebullition: similar scenes had occurred after the relief of the siege of Mafeking during the Second Boer War. Mafeking, however, changed very little. The First World War changed Britain forever.

Four years, 14 weeks, two days. Many people knew exactly how long the war had lasted. For soldiers still at the Front, it was hardly over. ‘Fine day but cold and dull,’ noted Field-Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, the British commander-in-chief, in his diary; he was at Cambrai, in northern France, organising an advance into the German sector on a front of 32 miles.

‘The state of the German Army is said to be very bad,’ he continued, ‘and the discipline seems to have become so low that the orders of the officers are not obeyed.’

When, in Belgium, the colonel of the 1/2nd Battalion Monmouthshire Regiment announced that peace would be declared in an hour’s time, they were too stunned to cheer. At exactly 11am, as they rested during a march, the commanding officer ‘raised his hand and told us that the war was now over. We cheered and with our tin hats on and our rifles held aloft, cheered again’. They were soon shocked to discover that they had to continue the march.

Elsewhere, a lieutenant with the 103rd Field Company of the Royal Engineers was called out into the garden by the villager on whom he was billeted. After some grubbing in an overgrown garden, a long-buried bottle of wine was produced. ‘We crowded into his front room, where, it being very cold outside, the stove and its long pipe were heated red-hot; we toasted everyone in turn.’

Safely back in England, Sgt-Maj Arthur Cook didn’t know whether to be pleased or furious; he’d been longing for a ‘nice Blighty wound’ that would send him home and, now that he’d got one, it proved to be distinctly surplus to requirements.

In Tanganyika, the King’s African Rifles got the news at 5pm. ‘I can’t realise it,’ wrote John Bruce Cairnie in his diary, ‘that the war is finished, probably because we are so far from everything.’ As he ate dinner outside, he could hear ‘sounds of revelry all over the camp, altho’ I don’t think the askaris know what has happened, except in a vague way’.

Lionel Dunsterville was in India. He was the British general – a childhood friend of Kipling – who had exuberantly led the ‘Dunsterforce’ across the Caucasus, briefly capturing Baku, only to be unfairly blamed when his tiny band withdrew, after a gallant action against an overwhelmingly larger Turkish army. His daughter Susanna and a friend arrived by train, bringing ‘with them the wonderful news of: PEACE AT LAST! and this GREATEST WAR is over… Meantime I have been more or less forgiven’.

He looked forward to the command of a new brigade – although he presciently noted that ‘I do not believe now that the war is over that they will ever want any new Brigades’. His career, as were those of many other soldiers, was over. For the time, however, such thoughts – and their attendant bitterness – were put aside.

‘Dear Folks,’ wrote an American serviceman from Paris. ‘Anyone who was not here can never be told, or imagine the happiness of the people here. They cheered and cried and laughed and then started all over again…

‘Each soldier has his arms full of French girls, some crying, others laughing; each girl had to kiss every soldier before she would let him pass… There are some things, such as this, that never will be reproduced if the world lives a million years… There is no where on earth I would rather be today than just where I am.’

Bliss it was, in that dawn, to be alive.

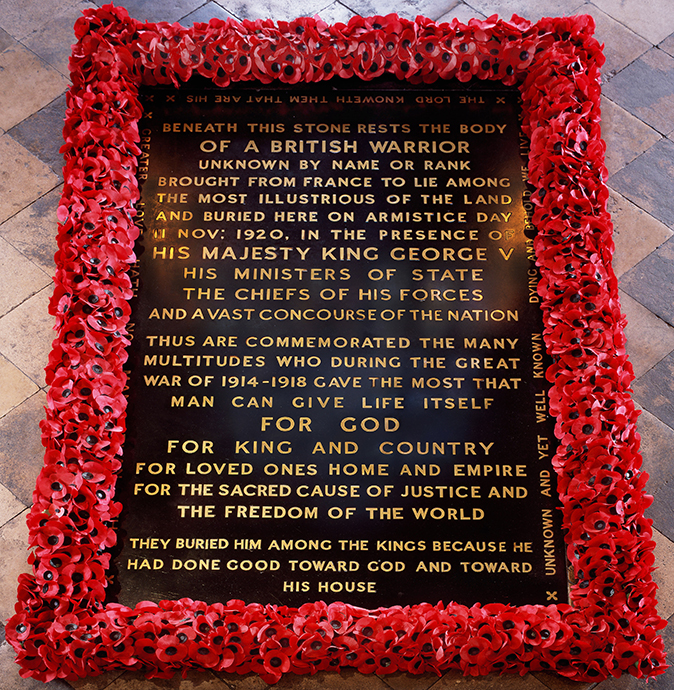

Armistice Day was not, however, only for 1918; it would recur as a fixed point on the national timetable on every anniversary of that momentous day. This thought must have been present in the minds of the Allied politicians even as they negotiated the end of hostilities, which took place, ritualistically, at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month. Everyone in Britain, from the Prime Minster downwards, knew that the end of the war would create a need for memorials and ceremonies to remember the sacrifice of the 900,000 servicemen who had died during it.

In Paris, the parade that followed the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, in the summer of 1919, had a natural focus in the Arc de Triomphe. London had no comparable monument that marching troops could salute.

Lloyd George asked Sir Edwin Lutyens to design a catafalque; Lutyens, remembering a chance remark made years earlier, apropos a marble bench in Gertrude Jekyll’s garden that a friend had compared to the Cenotaph of Sigismunda, proposed the term cenotaph.

The word means a memorial built to someone buried elsewhere – particularly appropriate in the case of the First World War dead, because the decision had been taken early in the conflict that no bodies of the Fallen, however senior, should be repatriated. It was a wood-and-plaster affair, to be replaced by the present stone Cenotaph, in all its geometrical complexity, in 1920.

Although devoid of religious imagery, this almost abstract expression of pure architecture was immediately accepted by the public as a great national symbol, but a movement was under way already, across the country, to build local memorials. Located on village greens and in churchyards, as well as in town halls, schools, colleges, offices, factories, railway stations, synagogues and chapels, they would become a new feature of the daily landscape.

Memorials of this type – remembering everyone from a locality or institution who had fallen – had barely been known before. They now took a variety of forms, from plain simple crosses to sculptural groups, from lettered monoliths to memorial halls. All enshrined the memory of that first Armistice Day, relived each November.

Meanwhile, in every theatre of the conflict, battlefield cemeteries – hastily dug to bury the newly dead – were being replaced by the Classical architecture, serried headstones and garden planting of the Imperial War Graves Commission.

By the first anniversary of Armistice Day, the euphoria of November 11, 1918, had subsided. How should it be marked? Today, the ceremonies are so familiar as to seem immemorial and yet they had hardly been considered a fortnight before the event took place.

It was Sir Percy Fitzpatrick, who had served as High Commissioner in South Africa during the war, who submitted a memorandum to the Cabinet suggesting a practice that had been adopted there: ‘Silence, complete and arresting, closed upon the city… Only those who have felt it can understand the overmastering effect in action and reaction of a multitude moved suddenly to one thought and one purpose.’

The King decided the silence to remember what he called the Great Deliverance should last for two minutes. Huge crowds gathered around the temporary Cenotaph as wreaths, sent by the Royal Family and others, were laid at its base. A new tradition had been born.

Such was its power that the public could have been forgiven for believing that their longed-for wish had been fulfilled and the First World War was truly over. Although this may have been true of the Western Front, the collapse of the Romanov, Hohenzollern, Hapsburg and Ottoman empires meant that violence continued in Eastern Europe, Russia, the Balkans, the Middle East, Greece, Turkey and elsewhere until at least 1923.

The Armistice itself, so wildly celebrated on November 11, 1918, may have contained a seed of future disaster: being only a ceasefire to negotiate a peace treaty, no Allied troops marched through Berlin, which allowed the Nazis to propagate the myth of the stab in the back.

But these anxieties were for the future. To the crowds and politicians of 1918, there was only one word that mattered: peace.

Ten stately homes which became hospitals during the First World War

To mark 100 years since the end of the First World War, The Royal British Legion draws our attention back

The grand Georgian house that served as a Red Cross Hospital in both World Wars

Felthorpe Hall stands in a wonderfully private setting at the heart of its 125 acres of formal gardens, woodland, lakes

Credit: Getty

How military watches have come from First World War necessity to 21st century icon

Military watches have come a long way from the trenches of the First World War – today, they're the choice

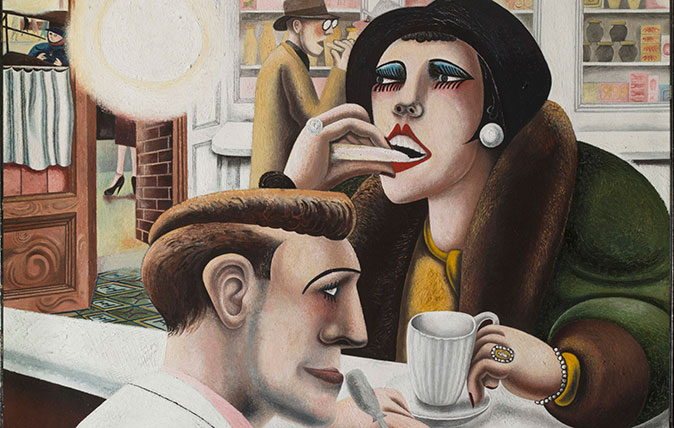

In Focus: The evocative, sensual masterpiece created in the wake of the First World War

Edward Burra was too young to have fought in the First World War, but his powerful oil painting The Snack