How to win at board games, from Monopoly and Cluedo to Scrabble and Snakes and Ladders

As millions of people around the country are set to have an enforced period at home, it'll be time to bring out the classic board games. But how can you make sure you beat the kids? Luck helps, but tactics are better as Matthew Dennison explains.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As you dust down the sets of Monopoly, Cluedo and Scrabble — a little dog-eared at the corners, their cardboard boxes marked by tell-tale wine-glass rings – don't for a second fall for the old fallacy that success is down to the capriciousness of fate, whether in the roll of the dice or the draw of the tiles from the Scrabble bag.

Luck evens out and success can be earned Country Life is here to offer a few clues on improving your skills. Beat the children and they may head off moaning towards the Playstation, but the sweetness of victory will last long into the night — even as you plunge in to another Netflix marathon.

Scrabble

Travel, and a familiarity with almost anything foreign, are key to winning at Scrabble. Authorities have claimed that the highest number of points that can be scored on a first go is 128 with muzjiks, a word for Russian peasants. Retsina, the name for resin-flavoured Greek wine, has seven permissible anagrams (stainer, retinas, anestri, nastier, ratines, retains and antsier) and, at seven letters, offers a 50-point bonus, although the highest-scoring word in Scrabble history is caziques, referring to West Indian chiefs, which (when played across two triple-word scores) scored 392 points.

Despite its usefulness, the letter 'S' features on only four Scrabble counters: astute players are advised to use their S counters judiciously. The addition of the suffix '-ish' to a number of words may well get you out of a temporary hole and, at moments of dire need, the answer could be to resort to words from which other players simply can’t profit, including ‘my’ and ‘that’. After all, it is Christmas.

Outrageously to many, there was a rule change to Scrabble in 2010 (the first in the game's history) which permitted the use of proper nouns. Expect younger players to pepper the board with names of pop groups and rappers, and laugh in glee at the fact that such names often throw in extra Xs, Qs and Zs. The only fair solution is to ensure you stick with your original set, and deny all knowledge (or acceptance) of the new state of affairs.

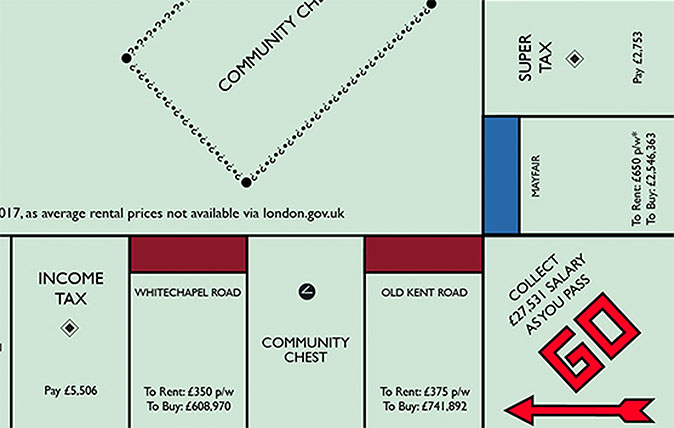

Monopoly

On the surface, Monopoly involves a higher degree of luck than knowledge, but tactical players invariably win the day. The 2015 UK and Ireland Monopoly Championship winner, Natalie Fitzsimons, advises concentrating resources on a single property group and mortgaging other properties if necessary, in order to achieve an ideal three houses on both or all three squares in a group.

She also advocates going to jail on a regular basis, which can enable players to avoid landing on a number of dangerous squares – unless, of course, your household rules claim that you can't earn rent from others while you're behind bars. And buy lots of houses as soon as you can: players who buy up large quantities of houses potentially benefit from preventing other players from doing so – eventually, the stock of houses will run out.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

More than other games, Monopoly is a game in which we reveal ourselves as creatures of habit. The square least often landed on is Park Lane, but British players remain attached to it. For this and similar reasons, many people are surprised to discover not only that the game is an American invention, but that, in its first incarnation, it was patented in 1903 by a left-wing feminist called Elizabeth Magie.

She called it The Landlord’s Game and wrote with some asperity: ‘It contains all the elements of success and failure in the real world, and the object is the same as the human race in general seems to have, i.e., the accumulation of wealth.’ The original board layout included a ‘poor house’ and a square out of bounds to players labelled ‘owner, Lord Blue Blood, London, England’. Another square bore the motto ‘Labor upon Mother Earth produces wages’.

For a long time, Miss Magie’s contribution to the invention of one of the world’s most popular games went unacknowledged. That's because it wasn't her version which became famous: a man named Charles Darrow happened to play the game one night in the 1930s and appropriated it for himself, renaming it Monopoly. It was Darrow who made it a success, and who subsequently sold it to Parker Brothers, who in turn licensed it to Waddingtons in Britain before they'd even put their new sets into production.

Darrow made millions in royalties; Miss Magie's patent was bought by the company after they discovered her contribution, but it's believed that she received less than $500 – probably less than she'd spent trying to assert her claims to its invention, according to a New York Times report.

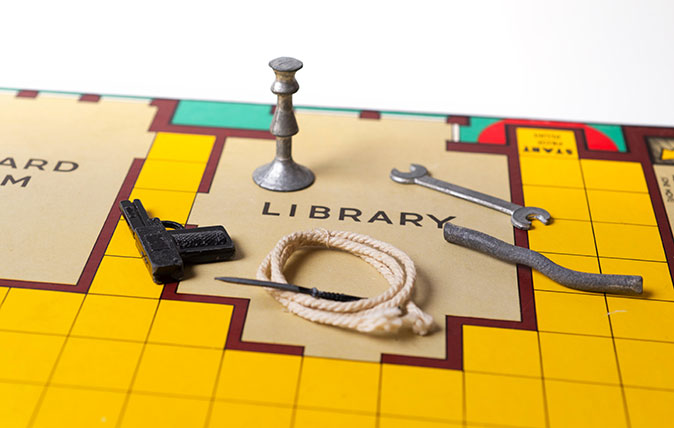

Cluedo

Cluedo, unlike Monopoly, is a British invention, although it’s spawned a number of foreign variants since its introduction in 1949. It was the brainchild of Anthony Pratt, a Midlands pianist – and one-time accompanist of Kirsten Flagstad – who was inspired by themed murder-mystery evenings in the hotels in which he played the piano. A fan of the novels of Raymond Chandler and Agatha Christie, Pratt initially intended Cluedo as an enjoyable way of passing time in wartime air-raid shelters.

Like real-life detection, Cluedo involves its players in amassing information. Successful players suggest creating smokescreens: spend time in rooms that are already among the cards you yourself, and ask questions that include answers on cards you already have. You'll narrow down the responses you’re likely to receive, and might lay a false trail of suspicion for object, places and people who you know are not involved.

Really serious players make notes, but this is clearly not in keeping with the spirit of Christmas games – or compatible with the perils of the seasonal drinks table.

Snakes and Ladders

Okay, there's no tactic to help you win this one — it's down to the roll of the dice.

That said, we have had great success at times with the following tactic. When needing to roll, say, a three, simply chant the following mantra as you shake the dice in your hand, with the actual rolling of the cube coinciding with the final word: 'Lucky three! Lucky three! Lucky lucky lucky THREE!'

It won't work every time, of course — we reckon the success rate is probably 1 in 6 — but my goodness, the kids are always very impressed every time we do manage to pull it off...

A version of this article was originally published in Country Life in 2018.

Credit: London Fox Lettings

What the Monopoly board would look like at 2017 prices

The iconic board game reimagined with a modern twist.

Credit: Sportsfile via Getty Images

Sporting Life: Marcus Armytage previews the National Hunt season

For many racegoers, the changing of the clocks signals the start of the National Hunt season proper. Marcus Armytage reveals

Credit: Kevin Murray

Sporting life: 18 golf courses in the UK that every golfer should play before they die

Roderick Easdale nominates his pick of the best golf courses in Britain and Ireland, with some help from the great

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.