Book review: Oliver Messel: In the Theatre of Design

Alan Powers admires the gorgeously produced study of the oeuvre of the celebrated 20th century designer Oliver Messel

To order any of the books reviewed or any other book in print, at

discount prices* and with free p&p to UK addresses, telephone the Country Life Bookshop on Bookshop 0843 060 0023. Or send a cheque/postal order to the Country Life Bookshop, PO Box 60, Helston TR13 0TP * See individual reviews for CL Bookshop price

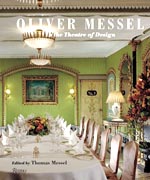

Biography Oliver Messel: In the Theatre of Design Edited by Thomas Messel (Rizzoli, £45, *£35)

The subtitle of this sumptuous new book on the designer Oliver Messel (1904-78) is well chosen. Messel made his name as a stage designer, working precociously for Sergei Diaghilev in 1925, shortly after leaving the Slade School, and becoming one of the leading designers for opera and neo-Romantic drama (notably by Christopher Fry and Jean Anouilh) in the post-war years. He also designed several films, including Caesar and Cleopatra with Vivien Leigh in 1945 and Suddenly, Last Summer with Katherine Hepburn and Elizabeth Taylor in 1959, his work for the movies being the subject of a chapter by Keith Lodwick, one of the four specialist author-contributors to the book, which also includes reminiscences by Messel's friends and colleagues.

Theatre design led to interiors, such as lavish, ephemeral party decorations. More enduring was the suite at The Dorchester (1954), recently refurbished by Thomas Messel, a furniture specialist and the editor of this tribute to his uncle. In the final years of his life, Messel moved from interiors to architecture, with a series of houses in Barbados (where he went to live) and Mustique. These are described, as is Messel's other interior work, by Jeremy Musson.

The introduction by Thomas Messel provides vital information on the alliance of an Anglo-German banking family to an artistic one. Oliver's sister Anne, mother of Lord Snowdon, inherited their maternal grandparents' house at 18, Stafford Terrace, Kensington, now the Linley Sambourne House museum, and ensured its preservation as a Victorian time capsule. Oliver grew up at Nymans in Sussex, a re-creation of a medieval manor house filled with lavish collections. Stephen Calloway writes illuminatingly on ‘Oliver Messel and friends'. A buoyant swimmer in the worlds of Eton and the Slade, Messel was a practical joker who described himself as ‘a mischief maker', but inspired great affection. He also worked incessantly and intensely, as the chronology at the back of the book shows.

Messel's theatre work in the early years had a steely glint of Art Deco, but this soon gave way to the ascendant Romanticism found not only in Britain, but in French stage design and interiors, that was lightly brushed with Surrealism. Evocation and visual deception were all-important, whether they involved faux materials or trompe l'oeil painting. This was a theatrical world extending well beyond the theatre, an act of resistance against the spirit of the modern age whose butter-fly touch was perhaps the most convincing form of persuasion. Sarah Woodcock gives an excellent account of ‘Messel on Stage'. Set models give a convincing impression of his creations, but it is hard to recapture their legend-ary appeal and popularity.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

If, despite the excellent photography of Derry Moore and others, and the riches of the Messel archive at the V&A, effects of sound, light and movement still need to be brought to animate the stage, they must come from the reader's imagination. It is hard to imagine a more enjoyable way of spending an evening as the nights draw in than to raise the curtain on this theatre of design.

* Give Country Life for Christmas and save up to 40%

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.