Curious Questions: How did 'God Save The Queen' become Britain's National Anthem?

As patriotic songs come under the spotlight, Martin Fone takes a look at national anthems across the world.

It was September 1745; London was on high alert. Bonnie Prince Charlie had just routed the English troops at Prestonpans and was about to march southwards. In a show of patriotic zeal, the entire male cast of Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist at the Drury Lane theatre announced that they were going to form a special unit of the Volunteer Defence Force to combat the Scottish menace.

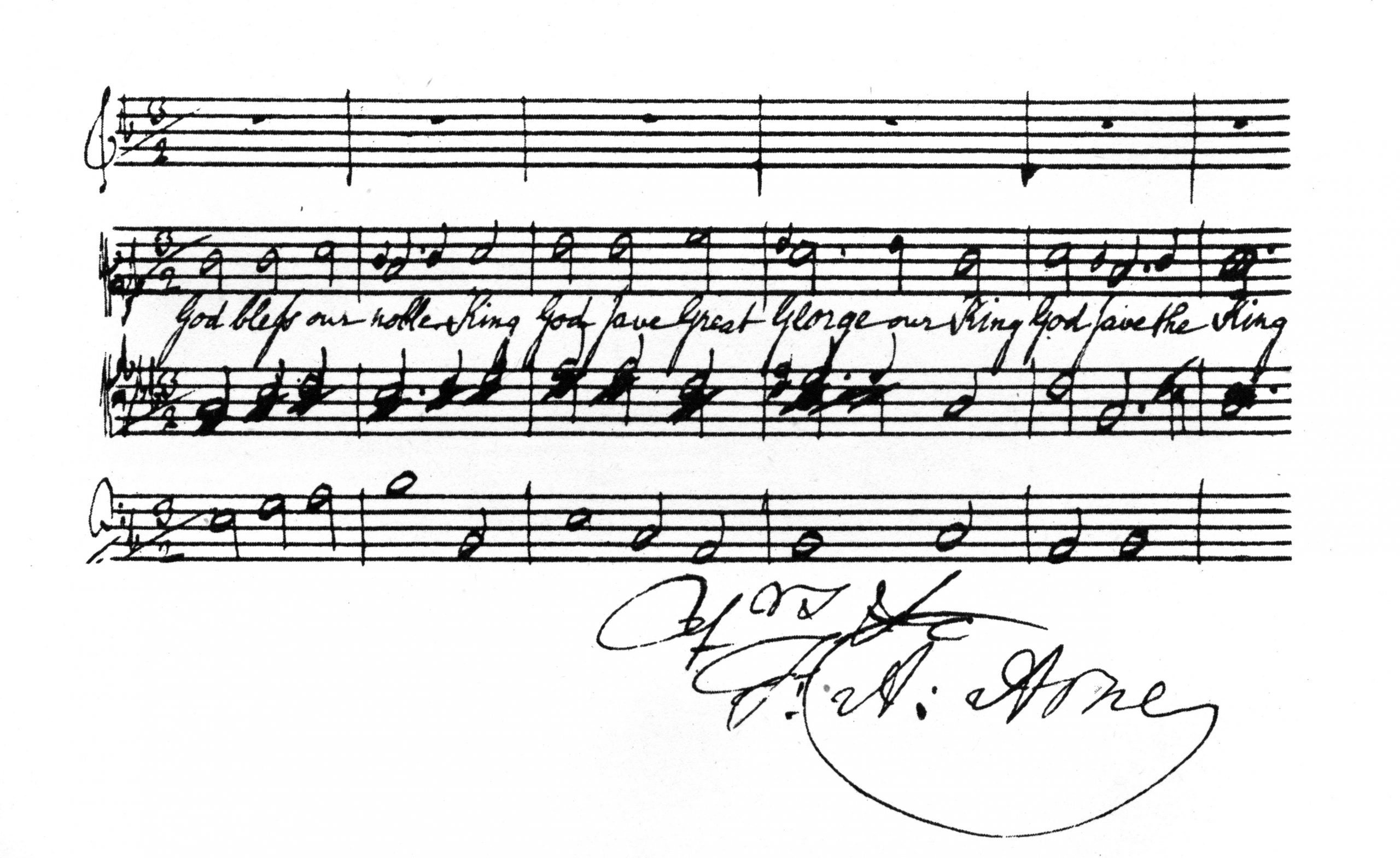

At the end of the performance on September 28th, Mesdames Cibber, Beard, and Reinhold stepped forward and sang, ‘God bless our Noble King,/ God Save great George our King’. The following day The Daily Advertiser reported that ‘the universal applause sufficiently denoted in how just an Abhorrence [the audience] hold the Arbitrary Schemes of our invidious enemies’.

Was this the first outing of our National Anthem? With patriotic songs increasingly under scrutiny, it is time to find out more about the tunes that nations have chosen as their international calling cards.

The sentiments behind our anthem are straightforward enough, an expression of loyalty and patriotic fervour which have a long legacy. The phrase, ‘God save King Henry’, was used as a watchword in an order of the Fleet at Portsmouth on August 10, 1544, with ‘Long to Reign Over Us’ as the counterword. In the days of good Queen Bess, Royal Proclamations routinely ended with ‘God Save the Queen’. The images of scattering our enemies and confounding their plans (verse two) were to be found in prayers from the 16th and 17th centuries in honour of the Sovereign.

As for the melody that accompanies the lyrics, it also has a long pedigree. It echoes a medieval plainsong, an old Scottish carol called ‘Remember O Thou Man’; it also cropped up in tunes which accompanied a rather energetic and vigorous form of dance, the galliard, popular in the Elizabethan court of the 16th century; and it is heard in a keyboard piece written, appropriately enough, by John Bull in 1619. The opening notes of the modern tune as used today were penned by Henry Purcell.

The Marquise de Créquy, in her book Souvenirs, published posthumously in 1834, claimed that the tune was composed by Jean-Baptiste Lully in gratitude for Louis XIV’s recovery from a rather unpleasant anal fistula operation he had endured in 1686. She went on to allege that George Handel plagiarised the tune for British use.

Tales of perfidious Albion always make good copy, but this is likely to be a baseless accusation. Charles Burney, who produced the setting for subsequent performances around the theatres of Covent Garden, claimed there was an anthem, ‘God Save Great James Our King’ in existence in the 17th century. Asking Dr Thomas Arne if he knew who the composer was, ‘He said that he had not the least knowledge… but that it was received opinion that it was written and composed for the Catholic Chapel of James II’. Arne’s role in the anthem’s development was to compile the version used at Drury Lane, although the lyrics had already been printed in the Thesaurus Musicus a year earlier, in 1744.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It was a hit and was soon played and sung whenever Royalty appeared in public. The Gentleman’s Magazine published the lyrics in October 1745, but soon voiced doubts about their appropriateness, declaring in December that year that ‘the words have no merit but their loyalty’. The magazine proposed a new version, beginning, ‘Fame, let thy trumpet sing’. Arne’s version may be dull and a tad pedestrian, but as no one came up with anything that was better or more popular, the 1745 Anthem, with modest alterations to reflect the gender of the reigning monarch, became the accepted version.

Curiously, though, ‘God Save the Queen’ has never been officially adopted as our National Anthem, its status owing to custom and use rather than legislation. It was only known as the National Anthem once Victoria had ascended the throne.

Its unusual rhythmic pattern – 6.6.4.6.6.6.4 – intrigued some of the finest composers. Beethoven, declaring that he must show ‘the English what a blessing they have in ‘God Save the King’’, included the theme in his Wellington’s Victory, a piece scored for the accompaniment of muskets and cannons.

Brahms featured the melody in his Triumphlied, while it provided Haydn with the inspiration to write Deutschland über Alles. The National Anthem of Lichtenstein shares the same melody, albeit with different lyrics.

The official adoption of anthems by nations is a relatively modern phenomenon, the Marseillaise being the first, in 1796. Once Napoleon had his feet firmly under the table it had to give way to the Chant du départ, returning to favour once more in 1830.

The wordless La Marcha Real, the royal anthem of the Spanish monarchy since 1770, was not adopted as the nation’s official anthem until 1939. The Star-Spangled Banner only became the anthem of the United States in 1931.

At the other end of the scale, the Wilhelmus van Nassouwe, although only adopted by the Netherlands as their official anthem in 1932, can be traced back to the Dutch struggles for independence from the Spanish empire in the 16th century. Dating from at least 1572, it can claim to have the world’s oldest music to accompany a national anthem.

The emergence of newly independent nations from colonial rule spurred the adoption of anthems, as did a decision in 1920 by the Olympic Charter to introduce the playing of national anthems to their medal awarding ceremonies. No nation with serious Olympic aspirations wanted their athletes to receive their medals to thunderous silence.

Anthems from around the world come in all shapes and sizes. Some can be truncated without losing any of their impact while others, often grandiose statements of ambition over reality, need to run their full, and often seemingly interminable, length to make any sort of artistic or patriotic sense. New Zealand and Denmark are so enamoured with the idea of an official anthem that they both have two each, while the Republic of Cyprus seems to live happily enough without one. They are not alone in eschewing anthems as, technically, only Wales of the home nations has one.

Less is more, I always think, and as far as national anthems go, the Japanese may just have got it right. Their anthem, Kimigayo, is the world’s shortest, consisting of thirty-two characters and running to just eleven measures. It is based on a waka poem written during the Heian period, between 794 and 1185 CE, and the music was written by Yoshiisa Oku and Akimori Hayashi, with harmonies added in 1880 by Franz Eckert. Adopted as the Japanese empire’s anthem from 1888 to 1945, it was not formally readopted as their sole anthem until August 13, 1999. It is illegal, under Japanese law, to translate its title or lyrics, so, to spare the editor any inconvenience, I will not attempt to!

I find it truly extraordinary, this curious desire of nations to identify themselves with a piece of music. At least, the first verse of ‘God Save the Queen’ can be deployed as a form of patriotic timer, to ensure our hands are squeaky clean. I’m currently humming it several times a day.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Jason Goodwin: The second, little-known verse of our National Anthem

Our spectator columnist comments on this past Remembrance Sunday.

Credit: Alamy

10 fascinating things you should know about the Shipping Forecast

From the tragedy which sparked its inception to the modern tweaks which have had listeners up in arms.

Credit: Getty Images/EyeEm

Curious Questions: Who first discovered that washing your hands stops the spread of disease?

Washing your hands regularly is the single biggest thing you can do to help stop the spread of coronavirus. In

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.