Thomas Hardy's Wessex vs the real-life Dorset: Which bits are real, which dreams, and which are exact to the last stream and stile

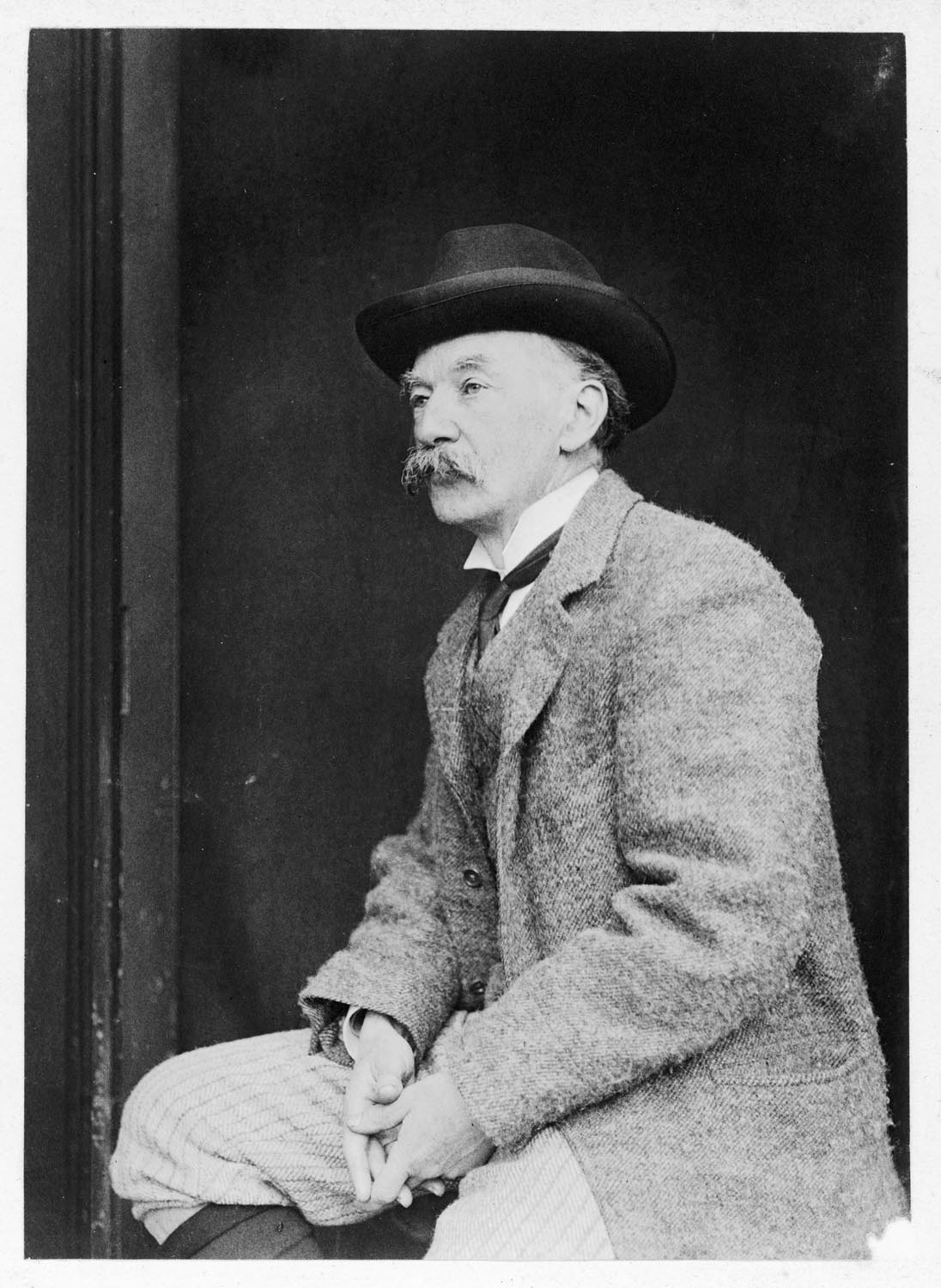

Thomas Hardy’s depictions of a fictional Wessex and his own dear Dorset are more accurate than they may at first appear, says Susan Owens.

We feel a frisson when a real place plays a key part in a novel. The Cobb at Lyme Regis will always be associated with silly Louisa Musgrove and her tumble in Jane Austen’s Persuasion and Knole in Kent with Virginia Woolf’s hero-heroine Orlando. Thomas Hardy, however, took the use of known locations to another level. He may have invented the characters in his novels, but he made them walk along actual roads, look across valleys at real views and live in recognisable villages and towns — sometimes, even in identifiable buildings.

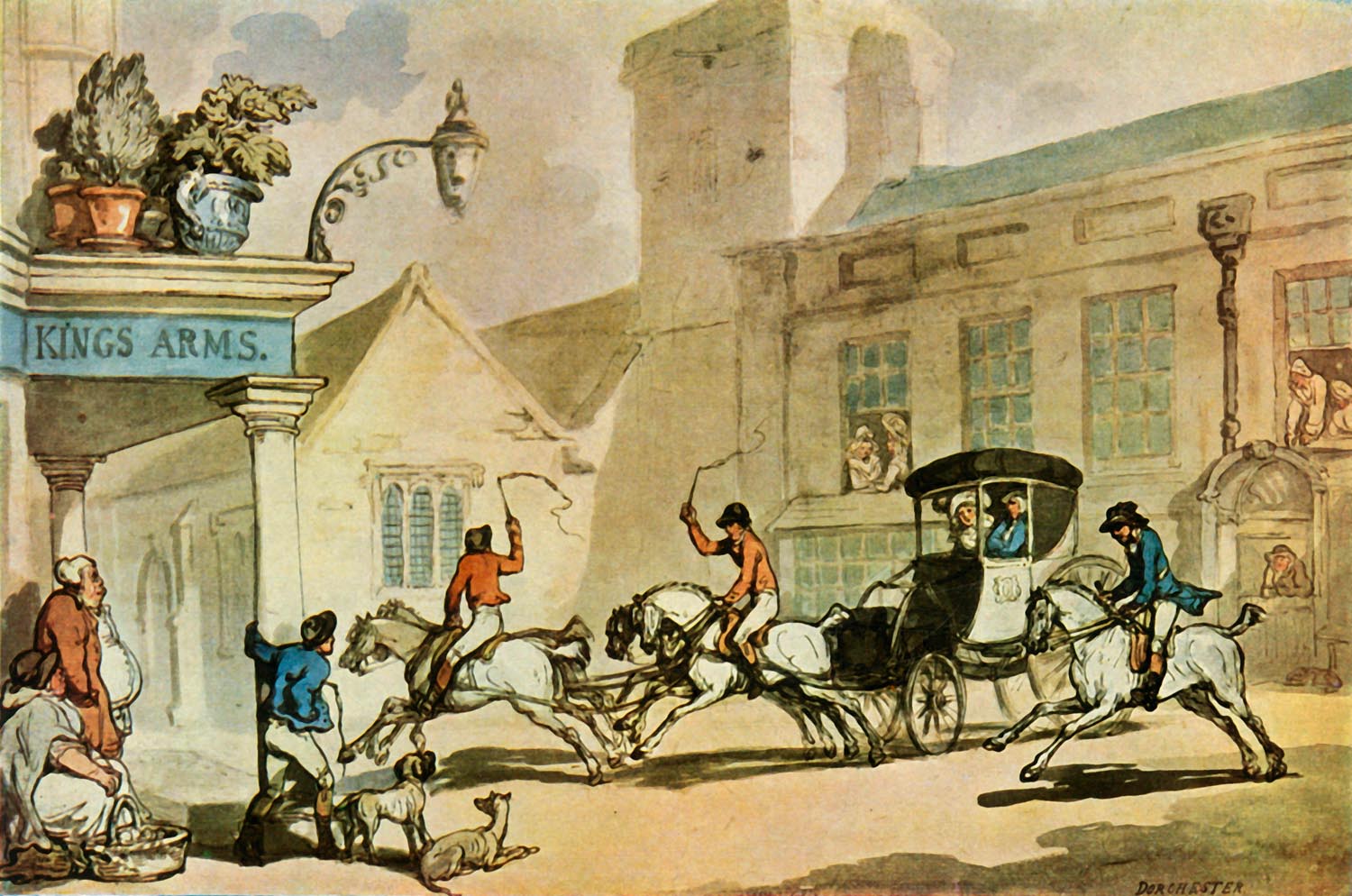

As a result, fact and fiction can shade disconcertingly into each other. A blue plaque now on the wall of a handsome building in the centre of Dorchester — the model for Hardy’s Casterbridge — reads: ‘This house is reputed to have been lived in by the MAYOR OF CASTERBRIDGE in THOMAS HARDY’s story of that name written in 1885.’ The word ‘reputed’ pokes a hole in the partition separating history from invention and lets through an unsettling draught.

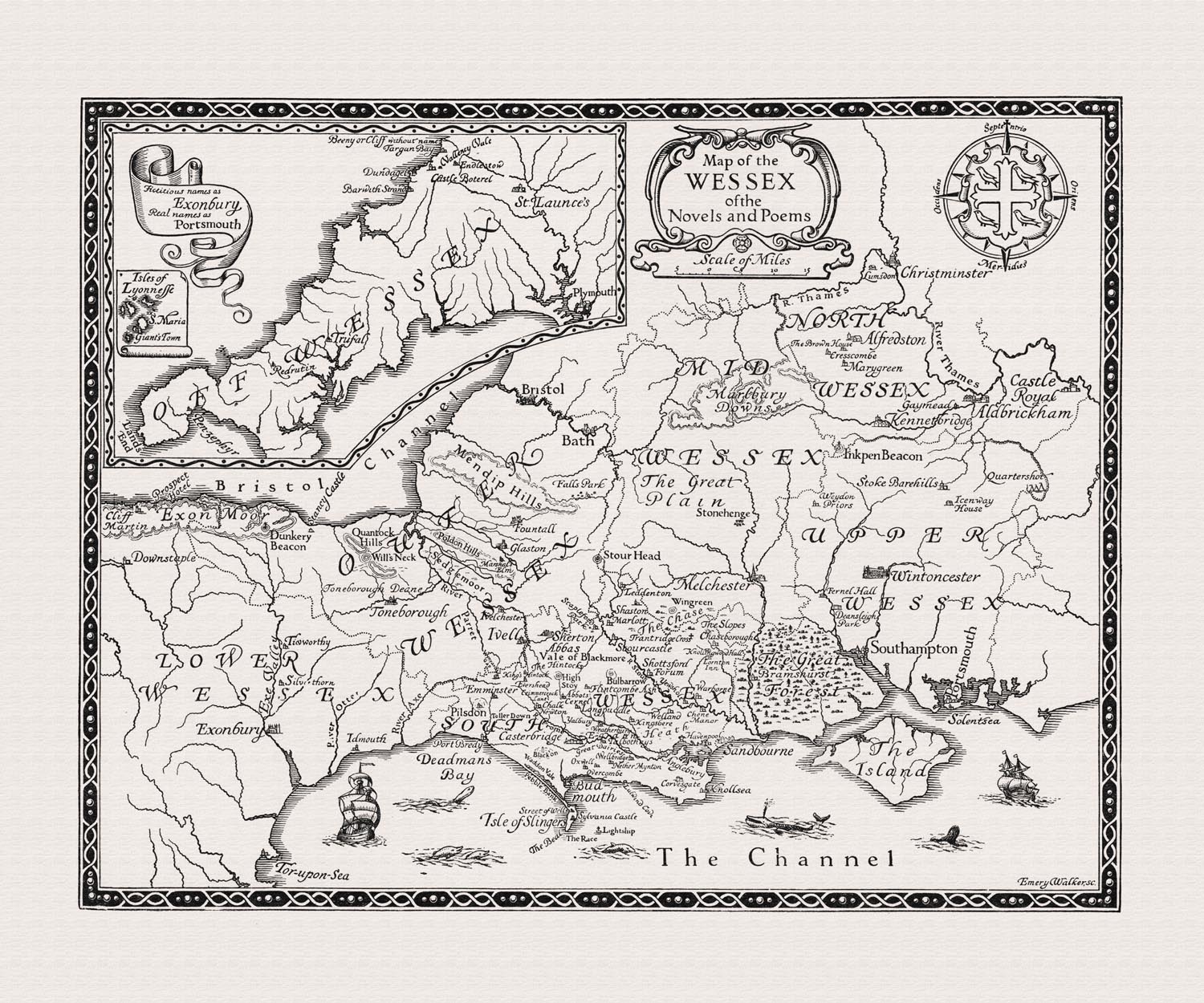

Needing a name for the large region, including his native Dorset, in which his characters lived, worked, loved and died, Hardy revived that of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom that covered south-west England: Wessex. He kept some place names almost intact — the Blackmoor Vale, for instance, Giant’s Hill and Stonehenge — but, for others, he invented an equivalent, often with an echo of the original: Cerne Abbas became Abbot’s-Cernel; Weymouth, Budmouth; and Bere Regis, Kingsbere.

Although Hardy was intensely concerned with place, he did not intend the towns and villages in his novels to be exact reflections of reality and admitted that his portraiture of individual sites ‘wantonly wanders from inventorial descriptions of them’. His characters inhabit an inbetween place, what he called ‘a partly real, partly dream country’. Where this countryman-writer was exact, however, to the last stile and stream, was in his depictions of the land and those who lived and worked on it.

Hardy was born in the small village of Higher Bockhampton, in a rambling building that stood between woodland and heath. It is this family home, built by his great-grandfather in about 1800, that he describes near the beginning of Under the Greenwood Tree (1872) as ‘a long low cottage with a hipped roof of thatch, having dormer windows breaking up into the eaves, a chimney standing in the middle of the ridge and another at each end’. From the age of 10, the young Hardy was sent to school in Dorchester, walking the three miles there and back every day in all seasons and weathers, getting to know Puddletown Heath and its inhabitants in intimate detail, whether bird, animal, insect or human.

Later, he channelled his boy’s-eye view into an episode of The Return of the Native (1878), a novel dominated by the vast stretch of Egdon Heath, which Hardy admitted to having composed from his knowledge of at least a dozen smaller patches of waste land. When Clym Yeobright cuts the furze in July, the heath — usually brown and forbidding — bursts into vivid life around him. Bees hum about his ears, amber-coloured butterflies land on his back, emerald-green grasshoppers leap over his feet and brilliant blue-and-yellow grass snakes glide in and out of fern dells.

It’s easy to picture the young Hardy on his hands and knees, eagerly observing these creatures. Or lying down in the middle of the heath, so that nothing was visible beyond its borders, to immerse himself in its atmosphere of ancientness and to feel ‘that everything around and underneath had been from prehistoric times as unaltered as the stars overhead’, as he was later to write.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As a walker, Hardy knew the feel of his native roads underfoot — how the dust of late summer deadened footfalls like a carpet and a hard frost made them ring. People do a lot of walking in his novels — it brings characters together on the road to exchange information, as well as deepening their connection with the landscapes through which they move. It also reveals character. Hardy was a connoisseur of gait.

Michael Henchard approaches Weydon-Priors at the beginning of The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886) with a ‘measured, springless walk’, which, Hardy tells us, ‘was the walk of the skilled countryman as distinct from the desultory shamble of the general labourer; although, in the turn and plant of each foot there was, further, a dogged and cynical indifference personal to himself’. Weydon-Priors was Hardy’s name for Weyhill near Andover in Hampshire, a place famous since the medieval period for its fair — where, within an hour or two, this possessor of a chillingly efficient walk will have auctioned off his wife.

Tess Durbeyfield’s foolish father shuffles along, his poor rickety legs causing him constantly to veer off the path, whereas she herself moves with a ‘quiescent glide… of a piece with the element she moved in’. Hardy’s Tess is so much a part of her environment that the landscape surrounding her reflects each phase of her story. She grows up in the gentle, somewhat isolated Vale of Blackmoor and is seduced by Alec d’Urberville in the Chase, the oldest wood in England. After Angel Clare’s rejection, she labours in the starve-acre fields of Flintcomb-Ash, a place that echoes her own emotional desolation. And, at the end, the authorities find her lying on the altar stone of Stonehenge.

For all its operatic symbolism, Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) is a novel in which practical footwear matters. Among its heart-breaking moments is when Tess’s walking boots are discovered stuffed in a hedge where she had hidden them, mistaken for a tramp’s pair and taken away, forcing her to walk many miles back home along a rough road in pretty, but thin-soled, patent-leather ones.

Those who live in the country come to know land by ear as much as by eye. Hardy’s characters are expert in this — even in the dark and when drunk, as in Desperate Remedies (1871): ‘Sometimes a soaking hiss proclaimed that they were passing by a pasture, then a patter would show that the rain fell on some large-leafed root crop, then a paddling plash announced the naked arable.’

Magically, Under the Greenwood Tree begins: ‘To dwellers in a wood almost every species of tree has its voice as well as its feature. At the passing of the breeze the fir-trees sob and moan no less distinctly than they rock; the holly whistles as it battles with itself; the ash amid its quiverings; the beech rustles while its flat boughs rise and fall.’ These are the sounds that guide members of the Mellstock parish choir, who meet on the road on a winter’s evening, each recognisable by his silhouette or the pale glimmer of a pair of spectacles. None of them bothers to carry a light, so familiar is the terrain to their ears and feet.

From his study at Max Gate, the house built to his own design just outside Dorchester, Hardy oversaw the first collected edition of his fiction, published in 1895–97. It gave him a chance to look back, not only over his novels, but also the ‘Wessex’ about which he had been writing for 25 years, as well as the occupations, beliefs and superstitions of its people. Over that time, the modern world had intruded into all aspects of country life and there was cause, he thought, to lament the passing of the old days and the old ways.

Hardy set Far From the Madding Crowd (1874) in Weatherbury, a place, he claimed, so closely based on Puddletown that many locations were once recognisable — until most of the thatched and dormered cottages were demolished. More profoundly, time-honoured traditions were becoming obsolete. ‘The practice of divination by Bible and key,’ Hardy wrote sadly in his preface to the new edition, ‘the regarding of valentines as things of serious import, the shearing-supper, the long smock-frocks, and the harvest-home have, too, nearly disappeared in the wake of the old houses.’

At the same time, ‘Wessex’ was, Hardy realised, becoming disconcertingly real — by degrees, his dream country had, as he put it, ‘solidified into a utilitarian region which people can go to, take a house in, and write to the papers from’. Poignantly, over succeeding years, both the novels themselves and popular guidebooks to Hardy’s Wessex brought tourists into the region by the trainload, eager to discover these enchanted locations — at the very point when many of them were being swallowed up by progress.

How to visit Hardy's Wessex today

Despite great changes, much remains of Hardy’s Wessex. Today, it’s possible to visit his birthplace at Stinsford and his later home Max Gate, both National Trust properties, and to have lunch at the King’s Arms in nearby Dorchester, where Henchard’s bankruptcy hearing takes place in The Mayor of Casterbridge.

We can even follow the route of the Mellstock Quire each Christmas with the Thomas Hardy Society. Hardy tourism is nothing new, however — since the 1890s, a map of ‘Hardy’s Wessex’ has been included in each of the novels. Generations of readers have gazed at the original of Bathsheba Everdene’s house in Puddletown and those of a macabre tendency have even lain down in the empty stone coffin at Bindon Abbey, to which the sleepwalking Angel carries Tess on their ill-fated honeymoon.

Yet Hardy himself did not always take it so seriously. When asked about the original of Little Hintock in The Woodlanders (1887), he replied: ‘To oblige readers, I once spent several hours on a bicycle with a friend in a serious attempt to discover the real spot; but the search ended in failure; though tourists assure me positively that they have found it without trouble, and that it answers in every particular to the description given in this volume.’

Hardy’s Wessex: The landscapes that inspired a writer

A 'ground-breaking' exhibition featuring the largest ever collection of Thomas Hardy’s personal artefacts is currently on display at four museums across Dorset and Wiltshire, including the Dorset Museum, Poole Museum, The Salisbury Museum and Wiltshire Museum. Running until 30 October 2022, the exhibition is ‘a once in a lifetime opportunity’ to see many of the writer’s personal objects, the majority of which have never been on display before.

Credit: Getty

Jason Goodwin: 'There was nothing there. The original message from St Petersburg, Sergei’s emails, the thank-you email. All gone.'

Our columnist Jason Goodwin recounts a chilling tale of his own brush with the Russians in Dorset.

The historic manor that inspired Thomas Hardy is a Dorset dream, with moat, gatehouse and a helipad

The highways and byways of scenic Wessex lead to a historic manor that inspired Thomas Hardy.

Credit: Old Came Rectory - Thomas Hardy's friend's house

A sprawling Dorset cottage for sale where Thomas Hardy met his inspirational mentor

Old Came Rectory is a delightful thatched cottage just outside Dorchester where one of Britain's greatest writers was a regular

A house for sale where Thomas Hardy broke his love rival’s heart

This lovely old vicarage in Cornwall has a quite incredible back story.

Credit: Knight Frank

Thomas Hardy's former home in south-west London — yes, London, not Dorset — is up for sale

This apartment on Trinity Road has been expertly updated to create a superb home on the doorstep of Wandsworth Common.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.