The best characters created Charles Dickens, still utterly unforgettable even 150 years after his death

Charles Dickens died 150 years ago, on 9 June 1870. Since then, Mr Micawber has become a byword for optimism, Scrooge for meanness and Uriah Heep for obsequiousness, and we still quote Mr Bumble’s ‘the law is an ass’. Rupert Godsal explains why these characters are so exuberantly unforgettable.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

No proper adjective derived from an author’s name — Wodehousian, Shavian, Wildean — is deployed with quite such frequency as Dickensian. We refer to Dickensian conditions (austere and squalid), Dickensian systems (archaic) and even Dickensian fog (a dreary pea-souper hanging damply in the air).

We speak of people being Dickensian in character, which might be, by turns, absurd, humorous or tragic, but, above all, memorable. If asked to name 10 characters from Trollope or Scott, many of us would struggle. Dickens is another matter.

[READ MORE: The life and times of Charles Dickens]

The names themselves are an art form: Susan Nipper, The Artful Dodger, Wackford Squeers, M’Choakumchild, Mrs Sowerberry, Anne Chickenstalker, Mr Guppy, Nicodemus ‘Noddy’ Boffin — each instantly conjuring an image. Uriah Heep (‘the ’umblest person going’) is the epitome of oily evil; the Veneerings are all front and social climbing; Allan Woodcourt, upstanding and a quiet pillar of strength.

There’s pompous Mr Bumble, the weak, oafish Noah Claypole and everyone knows what Scrooge is. And then there are the minor characters whose appearances are few, but whose names and characteristics are so striking: Mr Grimwig, Mr Creakle or Mr Pumblechook; Mrs Pardiggle, Polly Toodle or Flora Finching — they could all be major players in another story. Some say that Dickens over-egged the pudding, but his characters are not far-fetched — all of us know someone who is larger than life.

"Extreme they may be, but we feel for Dickens’s characters"

Reviewing Jeanette Winterson’s autobiography Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, Daisy Goodwin wrote: ‘Physically huge and 20 stone, and often wearing an electric corset that beeped when it overheated, Mrs Winterson, with her “revolver hidden in the duster drawer, and the bullets in a tin of Pledge” ready for the Armageddon, was a character that even Dickens might have thought a little over the top.’

Extreme they may be, but we feel for Dickens’s characters. He has been criticised for over-sentimentality, but who wouldn’t be affected by the death of crossing sweeper Jo in Bleak House? Or the selflessness and loyalty of Miss Pross, willing to take on the formidable Madame Defarge (what a personification of evil she is) in defence of her ‘Ladybird’ Lucie in A Tale of Two Cities? Or by the innate goodness of Joe Gargery in Great Expectations, always ready to forgive?

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

I have a soft spot for the Bagnet family from Bleak House. None is a major character, but all are likeable, real and amusing. Mr Bagnet is a former artilleryman who plays the bassoon ‘tall and upright, with shaggy eyebrows and whiskers like the fibres of a coconut, not a hair upon his head, and a torrid complexion’.

"Daniel Quilp in The Old Curiosity Shop has a ‘ghastly smile… appearing to be the mere result of habit and to have no connection with any mirthful or complacent feeling’."

His three children are named after the barracks in which they were born: Woolwich, Quebec and Malta. Mrs Bagnet, ‘a little coarse in the grain, and freckled by the sun and wind; but healthy, wholesome, and bright eyed’, is the brains of the family. When his friend Mr George comes for advice, Bagnet sums it up: ‘George, You know me. It’s my old girl that advises. She has the head. But I never own to it before her. Discipline must be maintained. Wait till the greens is off her mind. Then we’ll consult. Whatever the old girl says, do — do it!’

Dickens is the master of evoking a character in the minimum of words: ‘She was a little dilapidated, like a house, with having been so long to let’ (Miss Dartle, David Copperfield); ‘an angular man’ with ‘no conversational powers’ (Mr Grewgious, The Mystery of Edwin Drood). Daniel Quilp in The Old Curiosity Shop has a ‘ghastly smile… appearing to be the mere result of habit and to have no connection with any mirthful or complacent feeling’.

Old Chuffey in Martin Chuzzlewit ‘looked as if he’d been put away and forgotten half a century before, and somebody had just found him in a lumber-closet’, and Miss Murdstone in David Copperfield is summed up by her handbag: ‘She kept the purse in a very jail of a bag which hung upon her arm by a heavy chain, and shut up like a bite.’

Dickens loved writing for, being on and directing for the stage. Perhaps his characters stick in the national psyche because they were created by an actor and lent themselves to being portrayed on stage and, later, screen. As Claire Tomalin says in her excellent 2011 biography: ‘All his writing is theatrical, his characters are largely created through their voices, and in due course he re-created them for public performance and spoke the lines on stage himself.’

Many of his books were dramatised as they appeared — Barnaby Rudge was on at the Lyceum when the book was only half-written. Film and TV adaptations of the novels, of which there are legions, tend to be star-studded, unsurprisingly, considering what fun the characters must be to play. However, it’s not only the major roles that attract leading actors — remember Phil Davis’s memorable turn as Smallweed in Bleak House (‘Shake me up, Judy!’).

There have been well over a dozen versions of Great Expectations since 1917, with a distinguished list of Miss Havishams: Margaret Leighton, Joan Hickson, Anne Bancroft, Charlotte Rampling and, more recently, Helena Bonham Carter. Gillian Anderson’s Miss Havisham (in 2011) was more convincing than many — younger, madder, smaller.

Alfonso Cuarón’s intriguing 1998 take on the same work, set in 20th-century America, provides a fascinating contrast; the story still works, with Gwyneth Paltrow as Estella and Robert De Niro emerging from the sea as the chilling convict Magwitch, which shows how easily Dickens can be adapted.

Only last year, the satirist and director Armando Iannucci gave his take on Dickens with the film The Personal Life of David Copperfield, starring Dev Patel in the title role, Peter Capaldi as Mr Micawber and Tilda Swinton as Betsey Trotwood.

A more extreme example was when Miss Piggy turned her trotter to the role of Mrs Cratchit in The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992). It really shouldn’t work — and some would argue that it doesn’t — but for me it does. The fact that these characters can be changed to such an extent yet still retain the essence of the original shows the strength of that original.

Everyone has their favourites and, doubtless, there are many omissions here, even if, without any difficulty, this article mentions some 60 of Dickens’s creations. But where are Sam Weller, Mr Dick and Mrs Gamp, Smike and Inspector Bucket? This only serves to emphasise the genius of Charles Dickens.

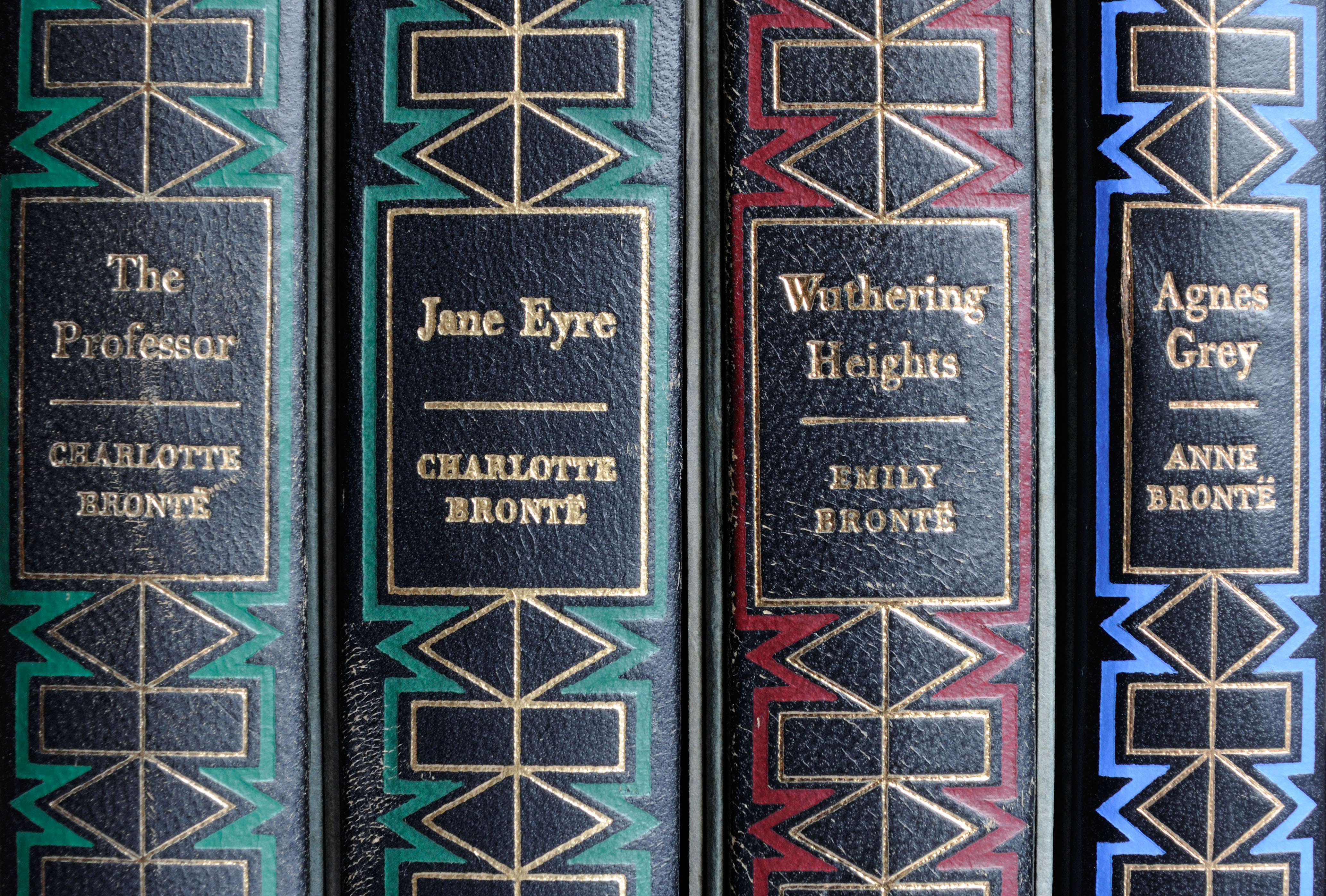

Inside Haworth: The humble parsonage where the Brontë sisters changed literature

Some of our most enduring stories were conceived at Haworth – Jeremy Musson enjoys a literary pilgrimage.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Curious Questions: Would Anne Brontë be more famous without her two sisters?

To mark the forgotten Brontë’s 200th birthday, Charlotte Cory looks back at the life and works of this ‘runt of

The house for sale where Charlotte Bronte and Elizabeth Gaskell forged their lifelong bond

Two of Britain's greatest novelists, Charlotte Bronte and Elizabeth Gaskell, shared a close friendship – and it all began at

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.