How the Bloomsbury Group shaped life in London WC1

There’s more to the Bloomsbury Group than squares, circles and triangles, says Rosemary Hill, who explores what drew its members to London’s WC1 in the first place and the lasting effect they had on it.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It was the American wit Dorothy Parker who described the writers and artists of the Bloomsbury Group as a circle who ‘lived in squares and loved in triangles’. Virginia Woolf, her sister, Vanessa Bell, and their friends Lytton Strachey, Roger Fry and Duncan Grant were among the best-known members of the set, whose influence in the years between the World Wars came to dominate intellectual life in Britain.

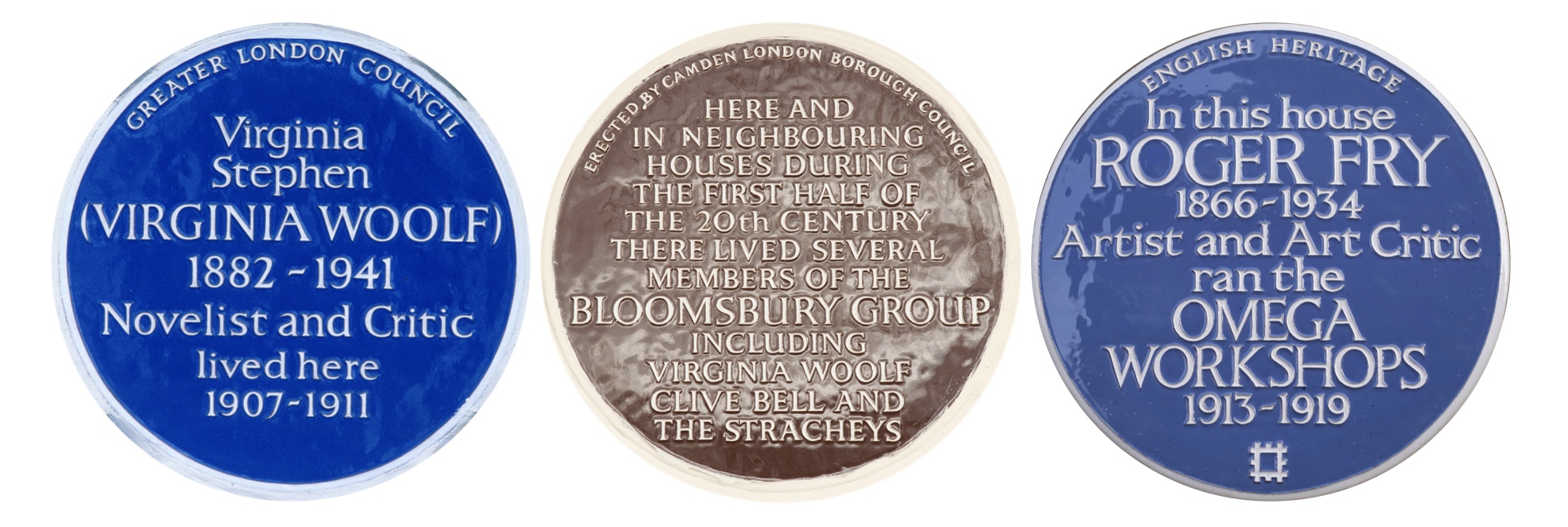

Their individual reputations have risen and fallen over the years. Woolf is perhaps more admired than in her lifetime, Strachey less, but, as a phenomenon, Bloomsbury — with its friendships, quarrels and complicated love lives — has become a biographical industry. A walk through the streets and squares of WC1 is punctuated by English Heritage blue plaques.

At the heart of Bloomsbury itself is the British Museum and the area is threaded with the buildings of London University, so it may seem an obvious place for writers and thinkers to gather. In 1904, however, it was a pioneering, indeed mildly scandalous thing for the four unmarried children of Sir Leslie Stephen, founding editor of the Dictionary of National Biography, to set up home together at No 46, Gordon Square. There had been attempts by the older generation to launch the girls, Virginia and Vanessa, as debutantes, but they found Society parties boring (Virginia managed to smuggle a book of Tennyson’s poetry into one dance).

Their brothers, Thoby and Adrian, recently down from Cambridge, had friends they found more interesting. Vanessa married one of them, Clive Bell, after which Adrian and Virginia moved to nearby Fitzroy Square. There they continued to hold the open-house Thursday evenings that marked the beginning of ‘Bloomsbury’ as a phenomenon. High-flown conversation about literature and post-Impressionist art was combined with intense emotional and sexual liaisons. Strachey was openly homosexual, at a time when it was illegal, and many of the group were bisexual.

The young Bohemians chose Bloomsbury not least for its cheapness. The area was first developed in the 17th century and was referred to by Alexander Pope as a fashionable address in the 18th century, but most of its streets and squares were built at the end of the Georgian period. The land belonged to the Dukes of Bedford, who began to develop it in 1775, when Bedford Square was laid out under the 5th Duke. After that, the buildings marched inexorably on from Russell Square all the way to Euston Road.

Builders James Burton and Thomas Cubitt gave the area the harmonious appearance that made it a smart residential area until the end of the 19th century, but it subsequently began to fall out of favour. By the time the Stephens and their friends arrived, it was satisfyingly raffish and down at heel. This suited their desire to shake off the stifling respectability of the dark and cluttered houses in which they had grown up.

Strachey recalled the architecture of his family home in Lancaster Gate as grotesquely disproportioned, ‘size gone wrong, size pathological... a house afflicted with elephantiasis’. In the orderly Georgian proportions of Bloomsbury, in houses with large windows looking out onto grass and trees, he felt he could breathe. The young generation was horrified by Victoriana, the bric-a-brac of what Woolf called the age of ‘crystal palaces, bassinettes, military helmets, memorial wreaths, trousers, whiskers, wedding cakes’, so they painted the walls white and hung modern art on them. The furniture was sparse, the curtains light.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Bloomsbury’s alternative to William Morris and the Arts-and-Crafts Movement was the Omega Workshops. These, too, were in Fitzroy Square, under the supervision of the critic Fry and, if the furniture they produced was not always well made, the patterns on the textiles and lampshades spoke of a bright, modern aesthetic. The British Museum, albeit not the first attraction of Bloomsbury, proved useful. As Woolf lamented in A Room of One’s Own, women were not admitted to the libraries of Oxford or Cambridge, but they could use the reading room at the museum and the London Library was not far away in St James’s Square.

This first, Edwardian, phase of friendship came to be known to its members as Old Bloomsbury. It belonged to a world that was rudely torn apart by the First World War. After 1919, they became more widely known, but they felt, as did their contemporaries, that an unbridgeable gulf had been made in history. The Omega Workshops closed, but Bloomsbury itself survived. Virginia, who had married her brother Thoby’s friend Leonard Woolf in 1912 and gone to Richmond, returned with him to Tavistock Square in 1924 and they installed their printing press in the basement.

From there, as the Hogarth Press, they published many of the most important writers of the day, from T. S. Eliot and Sigmund Freud to John Maynard Keynes (who lived in Gordon Square), as well as their own work. Meanwhile, the relationship merry-go-round continued to turn. Adrian Stephen had an affair with Grant, who had a child with Vanessa, who was married to Bell. In the 1930s, with the political climate in Europe growing darker, the Woolfs made their last Bloomsbury move in 1939 to No 37, Mecklenburg Square.

In 1940, it was bombed and, although they were out of London and unhurt, Virginia was heartbroken at the sight that met her when she returned. She described in her diary early in 1941 ‘the desolate ruins of my old squares: gashed; dismantled... Grey dirt & broken windows… all that completeness ravished’. Two months later, she took her own life.

Members of the Bloomsbury group lived on into the 1960s, but, increasingly, it was their legacy that mattered, the books, the pictures and the spirit that haunts the squares of WC1.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.