‘In Rome, you can see through the cracks of the world into all of human history’: Assouline's new book is a visual declaration of love to the Eternal City

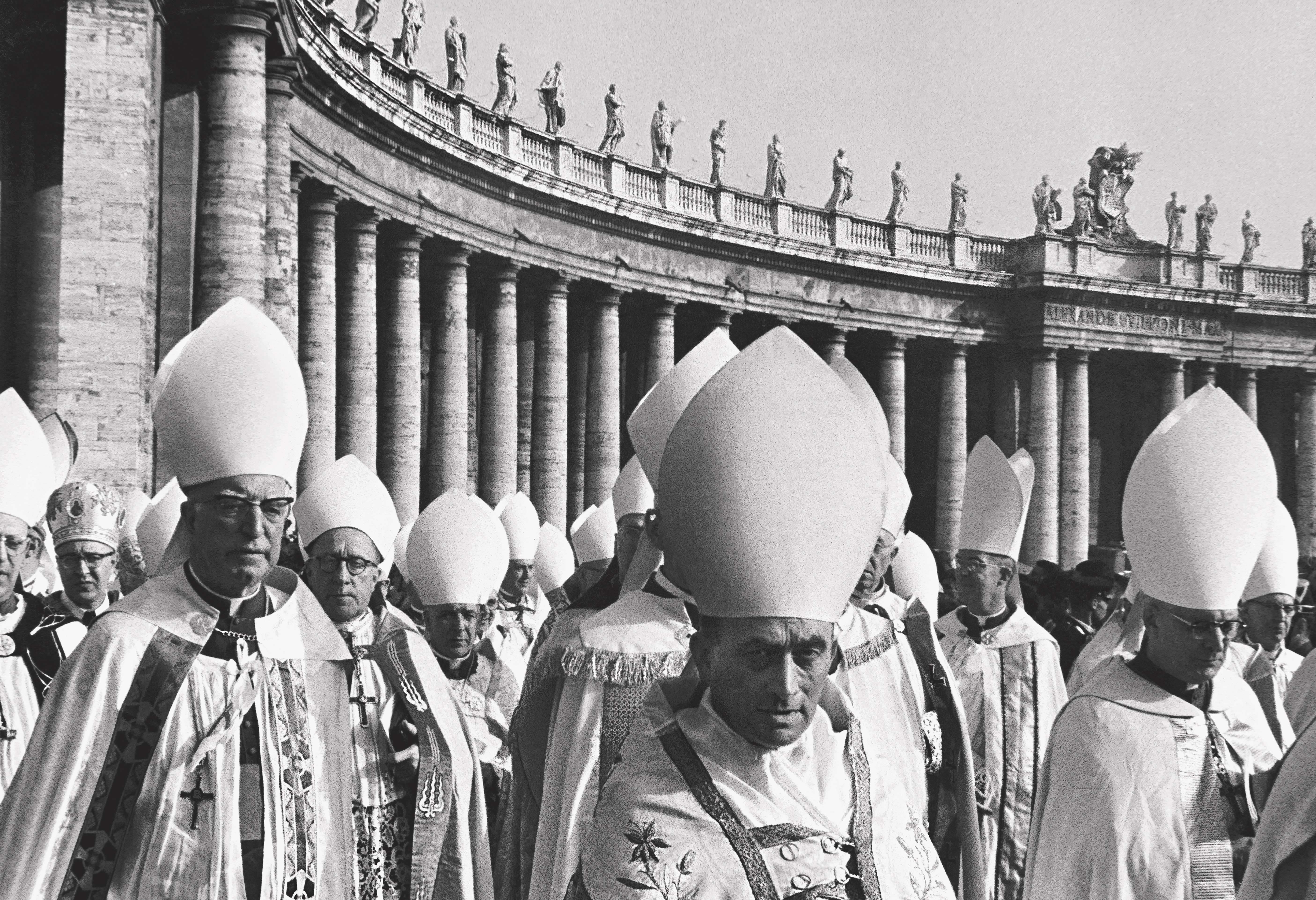

To mark the publication of Roma Eterna — which celebrates the Italian capital through the medium of photography — we asked one travel writer to write his own love letter to Rome.

‘What better place to observe the end of the world,’ Gore Vidal says, in Federico Fellini’s 1972 film, Roma, ‘than in a city that calls itself eternal?’

At the time, of course, the very American Vidal had been living at least part time in Rome for more than a decade. From his apartment terrace there, he could look down on the Largo Argentina where, 2,000 years earlier, the Republic had indeed ended with Caesar’s last stand (‘Et tu, Brute,’ etc.). But readers of Vidal’s essays or plays or historical novels will recognise in the above quip the writer’s favourite register: a little bit stentorian, possibly a bit ironic, and calculated to provoke.

I don’t doubt that he meant it in earnest though, and when I took an apartment in the same building overlooking the Largo Argentina, as news of our day regularly rattled well beyond parody and tragedy, I couldn’t help but agree with him. From the selfsame terrace where Vidal had installed himself to watch the apocalypse, I felt like I too could see the entirety of human history. But then Rome does that to you. As one building falls away to reveal another, centuries older, built on top of still another dating back millennia, you feel, in Rome, as if you can see through the cracks of the world into all of human history.

In Civilization and its Discontents, Freud went a step further, postulating Rome as a grand memory palace of our collective unconsciousness. A place not so much in the real world as in the psyche where all of history — everything that has ever happened — is happening, at once, presently. In Rome, all of our hopes and traumas, our joyous triumphs, heartbreaks and humble moments of life play out, concurrently. Here, Nero playing his fiddle, there, Caligula in full licentious flood, while Michelangelo hoists himself to his famous ceiling, and Caravaggio gets into all sorts of trouble.

Before I’d ever come to Rome, Freud’s bonkers metaphor for memory incarnate seemed a wild, if wondrous abstraction. But, when you are here, peering through layers of human toil and artistry, its suffering and poetry, reading in the city’s classical, Apollonian architecture all of civilisation’s efforts to contain and control the sinuous, Dionysian vines of Nature that constantly creep through the stones, cracking marble, breaking bricks, you see absolutely what Fread meant. Everything that ever was is, right now and forever, in Rome. Even if, later in life, Freud struggled with the idea that the continual construction, destruction and renovating of Rome messed up his metaphor, I continue to be amazed, walking by a chain coffee shop, by the pop song I can’t get out of my head, and think he was right.

I think my dad thought so. When, in my early 20s, pop and I finally became close, it was to Rome that he wanted to bring me. And forever afterward it was always to Rome, the place where he had had his great adventures in his youth — meeting the Pope, hanging with Zeffirelli — that his mind wandered. Because, I think I now understand, the Rome in my dad’s mind was, like Freud’s, existing somewhere outside of time, but containing all of it. Containing all of the versions of my dad, too, and all of his potential selves. I think that, in Rome, and in the Rome in his mind, my dad could return to the source material, to a point of possibility, where he could be any and all of his other selves. After all, if all roads lead to Rome, then surely we could take any one of them on the way out?

There is this thing that I do when I return to Rome after a long absence, rewalking the small sections of it with which I felt myself to be familiar, studying the changes, to feel what is different about Rome, of course. But I expect that what I am really noticing is what is different about myself, and my memory. If Rome does in fact contain, in its winding alleys and sprawling hills, the entirety of human history, I think now, that what it shows us is just a reflection. All we see in the oculus of the Pantheon, in the shards of light falling on the domes, and in the petrol sheen of the Tiber, is what we project there. If we have come expecting to see the end of times, or, indeed, to see ourselves as somehow outside of time, she will surely show us that. Rome never disappoints.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

'Roma Eterna' is published June 3 (Assouline, £85)

Christopher Wallace is a writer and photographer. His biography of the late photographer Peter Beard, ‘Twentieth-Century Man: The Wild Life of Peter Beard’, was published by Ecco press. Before going freelance, Wallace was the US Editor of Mr Porter and the Executive Editor of Interview Magazine. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, The Paris Review, and on Substack, among others. Chris was born and raised in Los Angeles and once upon a time made a few short films that won some awards at festivals. Longer ago than that, even, he played college football, before eventually quitting the team to write poetry. He still makes similarly poor career decisions — his words, not ours.