The best and worst of London's bridges, from the sheer elegance of Albert Bridge to the utilitarian solidity of Wandsworth

London's bridges are integral to an appreciation of the character of the city, as well as being great feats of architecture and engineering. Jack Watkins takes a look.

The idea of a Garden Bridge has been spiked and the last major Thames crossing to go up — the Millennium Bridge — got off to a shaky (quite literally) start before finally rooting itself in the public consciousness, but London has a proud heritage of finely engineered bridges.

Despite lacking the antiquity of Paris’s Pont Neuf, many have transcended their utilitarian purpose to become objects of visual delight in their own right. Ironically, given the name, that doesn’t include London Bridge, now formed from concrete and steel. In its earlier incarnations — including a series of timber bridges and the medieval stone structure that stood for 600 years—London Bridge was the capital’s sole Thames crossing beyond Kingston, until the first Putney Bridge was raised in 1729.

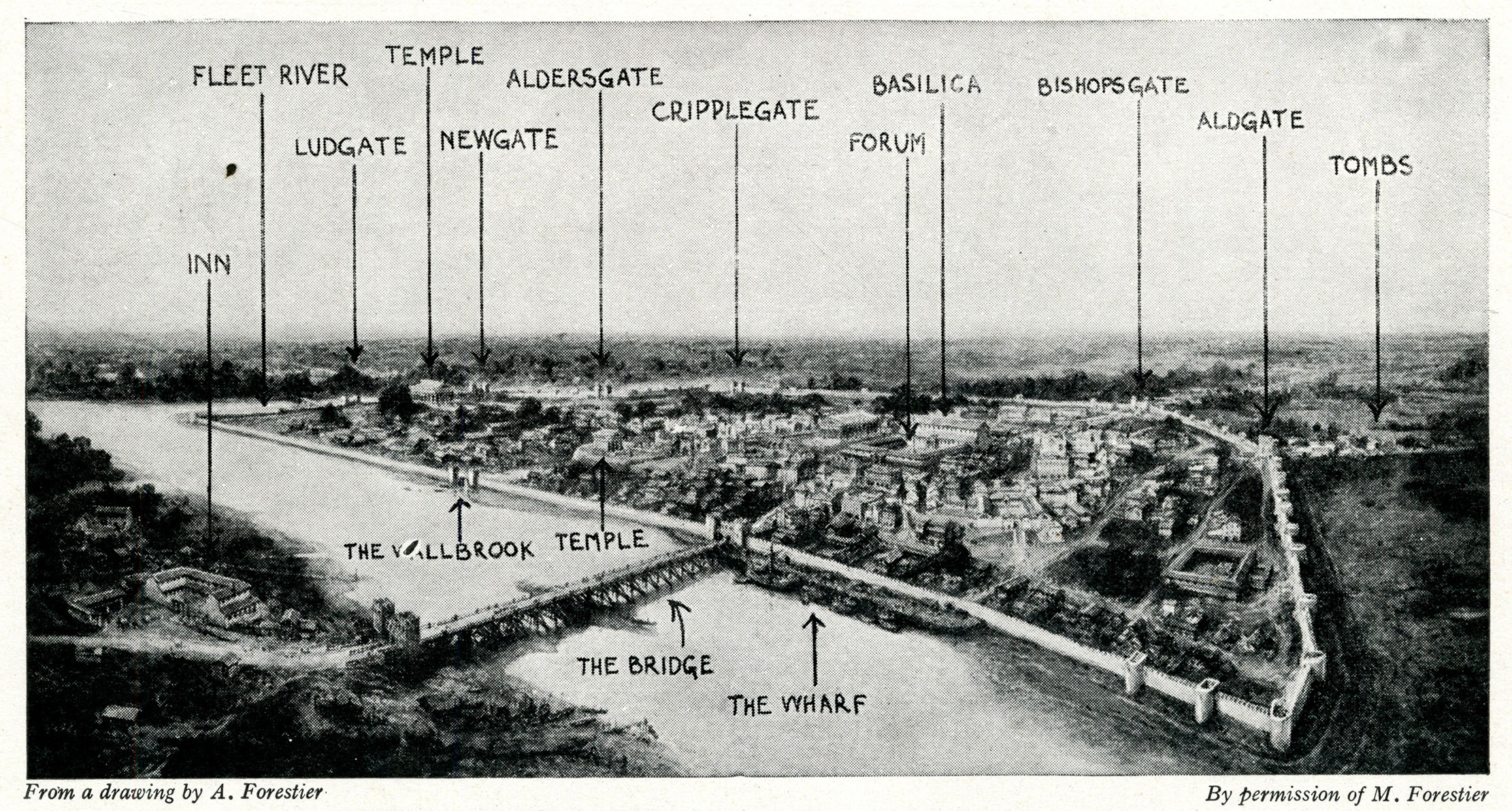

In fact, the first London Bridge, built by the Romans above the Southwark marshes in ad43, instigated such a rapid growth of London’s trading port that, by the end of the century, the settlement had replaced Colchester as the capital of Roman Britain.

The current crossing was completed in 1973 and its streamlined functionality has its admirers, but it’s hardly surprising that Tower Bridge outranks it as a tourist-industry marketing motif. Its famous Gothic towers, pure Victorian romanticism, house and support the bridge-lifting machinery and suspension cables.

Seasoned Londoners might feel that more interesting examples lie upriver. The granddaddy of the lot, Richmond Bridge, shares the distinction of being the only Grade I-listed span in London with Tower Bridge.

It’s also the last survivor from the 18th century, designed by Palladian country-house architect James Paine. With its five elegant Portland stone arches, it has a picturesque charm that matches the relaxed setting and, at 300ft in length, it’s less than half the span of those downstream.

Drifting back eastwards, the first of the larger-scale historic structures you encounter is Hammersmith Bridge, in a charmed spot where the architectural river skyline remains at its most Georgian and Turneresque. Old Hammersmith Bridge, built between 1824–27, was the first suspension bridge to span the Thames, but crowds darting from side to side to watch the University Boat Race caused the deck to sway alarmingly.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Sir Joseph Bazalgette, better known for his engineering of the Embankment and the capital’s still intact underground sewers, was brought in to design the new, more elaborate suspension bridge. Resting on the original pier foundations, it opened in 1887. This mighty iron edifice, with its imposing towers, looks a true creature of the Victorian age. As one of the most distinctive of the Thames bridges — now painted the original shade of green specified by Bazalgette — Historic England unsurprisingly upgraded its listing to II, in 2008.

However, designed to support horses and carts, Hammersmith Bridge struggled with the weight of modern traffic and is closed to motor vehicles as it undergoes a £120 million restoration. Pedestrians can still use it and, from it, there is a tree-framed, if not exactly solitary, walk along the Putney Embankment to Putney Bridge, another Bazalgette effort, this time in stone and Cornish granite and more prosaic.

It is in an attractive location, however, with the parish churches of Fulham and Putney at each end and the gardens of Fulham Palace on the north bank, and is the traditional starting point of the Boat Race.

Sadly, as we’ve discovered already, not every London bridge is a visual cracker and poor old Wandsworth Bridge has the reputation of being the least attractive of the lot. Beyond it, however, is an interesting stretch of river with three bridges, Battersea, Albert and Chelsea, in close proximity.

Battersea Bridge offers fine prospects from its position at a bend of the river, upstream from Wandsworth and downstream of the Albert Bridge and Battersea Park. Yet again the designer was Bazalgette and his structure of 1890 replaced the last of London’s wooden bridges, immortalised in J. M. Whistler’s Nocturne: Blue and Gold: Old Battersea Bridge. An attractive feature of this slender, low-slung, cast-iron arch bridge is the Moorish lattice decoration on the balustrading.

For sheer elegance, the Albert Bridge, the work of Rowland Mason Ordish, is unbeatable. This wedding cake of a bridge looks almost too dainty for a gritty capital city.

With its ornate kiosks and pencil-slim spires, its decoration is reminiscent of a seaside pleasure pier and it’s even more of a sight to see when illuminated.

Yet the genuinely fragile structure has been dubbed The Trembling Lady and a notice asks ‘All troops to break step’ when marching across it. Thankfully, to the joy of aesthetes, a plan to demolish it in 1973 was defeated by a campaign led by Sir John Betjeman.

At the south end of the Albert Bridge, a pleasant walk through Battersea Park brings you to Chelsea Bridge, a more recent suspension span (opened 1937) of pleasing profile. It’s the last of what you might term London’s leafy bridges.

Beyond, the backdrop becomes unremittingly urban, although, around another bend, lies a line of three more striking examples. These are the colourfully painted Vauxhall Bridge (1906), with big bronze sculptures on the piers; Lambeth Bridge (1932), which from its south side offers a view across to the Palace of Westminster much favoured by photographers; and Westminster Bridge, the oldest of all the big central London crossings (1862).

After these, the bridges become subsumed into the London of the picture postcards and artists — not least Claude Monet, who painted the predecessor of the current Waterloo Bridge more than 40 times. To public dismay, it was demolished in 1936 to make way for Giles Gilbert Scott’s replacement, which was heroically completed during the Second World War. Its modernity seems of a piece with the architecture of the South Bank.

Standing perched above the most dramatic of the curves of the Thames, you can look east to St Paul’s and the towers of the City and west back to Westminster and the airier districts beyond. London may not be the maritime settlement of past times, but its bridges remain integral to an appreciation of its character.

The story of Old London Bridge, the iconic landmark which vanished from the capital's skyline

Important new discoveries illuminate the form and history of the houses that lined one of London’s most celebrated lost landmarks.

Curious Questions: How does Tower Bridge work?

Tower Bridge celebrates its 125th birthday on June 30. But how does it work? And why was it built that

Curious Questions: Did a double decker bus really jump over Tower Bridge?

London's most famous bridge is 125 years old in 2019, but for all the marvellous facts there's only really one

Jack Watkins has written on conservation and Nature for The Independent, The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph. He also writes about lost London, history, ghosts — and on early rock 'n' roll, soul and the neglected art of crooning for various music magazines