London's lost masterpieces: The palaces and Georgian gems torn down in 30 years of 20th century madness

London would look very different had it not been for the widespread demolition of Georgian architecture in the 20th century. John Martin Robinson takes a look back at what was lost and what was fortunately saved.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In 1934, the Scandinavian architect Steen Eiler Rasmussen (1898–1990) published his classic, London: The Unique City, a deeply researched and subtle appreciation of London’s Georgian planning, layout and architecture, much of which was sadly to be lost or spoilt in subsequent decades.

Many of the buildings he described and illustrated have been destroyed, but his book is still in print and widely regarded as a classic of urban history. It is the best social and architectural analysis of London’s modern reincarnation and the development of its distinctive urban forms: low-rise, spreading, green with numerous garden squares, well planned according to building regulations introduced after the Great Fire of 1666 and codified in a series of three 18th-century building acts. They defined the width of streets and the height of buildings, prescribed building materials and enforced construction and fire-prevention standards. But they left the detailed design to individual builder-developers, architects and surveyors working for ground landlords such as the ‘Woods and Forests’ (Crown Estates), the Grosvenors, Bedfords, Portlands (now Howard de Waldens), Portmans, Sloanes (later Cadogans), through City livery companies and charities, down to small speculators, including the builder-architect Edward Shepherd in Mayfair, who developed the market behind Piccadilly that still bears his name.

The result was a sensibly planned, visually harmonious and well-proportioned layout with uniform Classical, but understated streets and squares (their proportions based on the Orders even when astylar), superb Baroque and Palladian churches (which carried on the architectural baton of 17th-century Rome in Protestant guise), as well as gardens with stately plane trees. Most of it was composed of terraced houses (in three grades, from gentry to artisans), but interspersed in the West End with about 40 aristocratic town palaces of great architectural distinction.

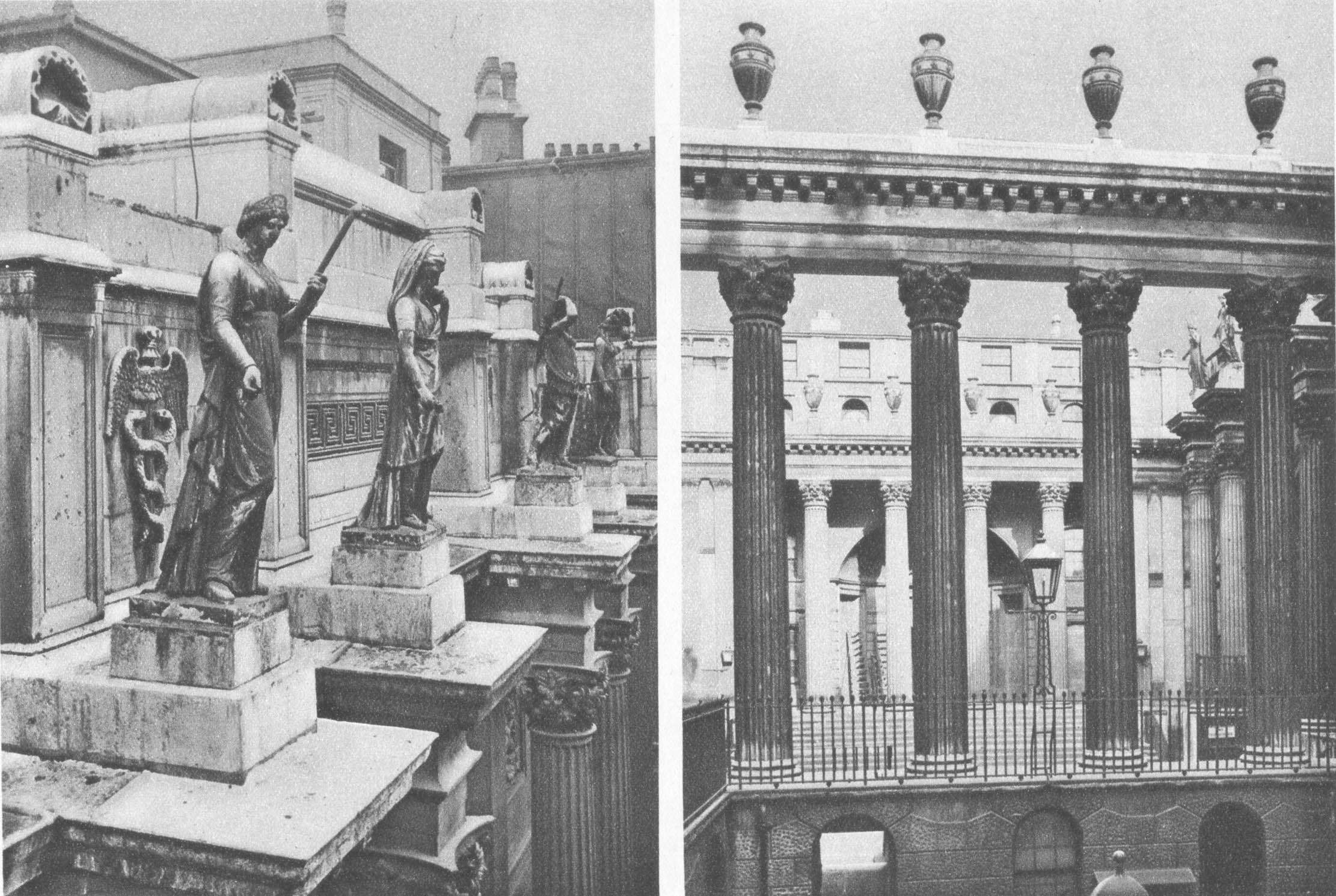

The most notable were Robert Adam’s Lansdowne House; Norfolk House with Rococo interiors by Giovanni Battista Borra, worthy of royal Turin; William Kent’s noble Devonshire House; Lord Chesterfield’s eponymous house with a colonnaded forecourt terminating an axis from Hyde Park; and Spencer House, with the earliest neo-Classical interiors in Europe. Only the latter survives.

Nor were distinguished public buildings lacking, from Kent’s Horse Guards, Gibbs’s St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Chambers’s Somerset House and Soane’s Bank of England to George IV’s Metropolitan Improvements and Smirke’s Grecian British Museum.

The key idea of Rasmussen’s book is that Georgian London was radically different from other European capitals where grandiose plans and architecture were dictated by absolute monarchies (including the Catholic Church). Rasmussen understood and celebrated the fact that Georgian London was the creation not of the state, but of a culturally aware and well-educated population that shared a common classic aesthetic.

He thought the planning and architecture of London should embody the British concept of constitutional monarchy, the entrepreneurialism of a sophisticated, visually informed aristocracy and a large, well-educated and prosperous professional and mercantile class. (Half the population of Georgian England was comprised of those three groups; what now would be called the upper and middle classes). He saw it as a model of urbanism, where a city’s future could be decisively influenced by self-reliant and ‘culturally educated citizens without dependence on the public sector’. (Nobody grasped that as a result of the Industrial Revolution, worldwide trade and explosive population growth, the visually aware section of England and the capital’s population had shrunk, as a proportion of the whole, after the 18th century.)

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Although sophisticated 20th-century European critics, such as Rasmussen or Pevsner, admired London’s architectural beauties and were drawing contemporary lessons for cohesive social planning and aesthetically pleasing modern development from London’s Georgian townscape, many of its own citizens and most of its public sector were more influenced by a crude version of American capitalism, which saw the historic fabric not as a socially cohesive and aesthetically beautiful artefact, but as an opportunity for profitable short-term business speculation. There was mass urban destruction between the 1930s and 1960s, of which only a small part was due directly to the Blitz.

The ruination could have been worse if a heroic fight back had not gained traction and halted the demolition after 1970. Regent’s Park, Islington, some of Bloomsbury, all of Belgravia, parts of Kennington and Westminster (especially Covent Garden and southern Mayfair) survived by the skin of their teeth and were restored, but much was lost.

Soane’s Bank of England, George Rennie’s Waterloo Bridge, Adam’s Adelphi, Nash’s Regent Street, nearly all the aristocratic town houses, the east side of Berkeley Square, chunks of Park Lane, the Foundling Hospital, the northern part of the Bedford estate, including Woburn and Tavistock Squares (after sales for death duties), all except three of the houses by the Adams and Wyatts in Portman Square, even Athenian Stuart’s Montagu (Portman) House, were torn down.

This shameful destruction was unique to London. In Paris, Rome and Vienna, the town palaces became embassies or museums in the 20th century, whereas the general fabric of the centro histórico was protected by strong state ordinances: the Committee for Paris (instituted in the 1870s), in the case of the French capital, or laws dating back to the 16th century in the case of papal Rome. The very freedoms, individuality and flexible planning that created Georgian London turned out to be its nemesis.

Without strong government-imposed preservation laws, there was nothing to halt the architectural ravages. Ruskin and William Morris had pioneered the cultural conservation movement in the 1860s and 1870s. The Ancient Monuments Protection Act of 1910 initiated state preservation of historic buildings in England (on the model of that in British India), but the 1910 Act, administered through the Ministry of Works, and bodies such as SPAB (founded by Morris) were only concerned with buildings from before the reign of Queen Anne.

Georgian was ‘modern’ and of ‘no historic interest’, leaving a large open goal, until the Georgian Group was founded as a breakaway from SPAB in 1937. ‘Antiquarian prejudice’ was exacerbated by the Modern movement in architecture, which preferred a tabula rasa and thought ‘restoration’, or concern for the historic townscape, was ‘pastiche’ or ‘socially irrelevant’. Concrete, Soviet-style, high-rise, proletarian housing was better than old terraces.

The poor calibre of local government in the boroughs must also bear some of the blame, but there was an exception in the London City Council (LCC; Greater London Council after 1965), which, from its beginning in the 1890s, was not a philistine body, but operated from a Classical palace (diametrically opposite the Gothic Palace of Westminster) with malachite urns given by the Tsar in its Council Chamber and marble fireplaces given by the King and government of Italy in its entrance hall, as well as an excellent reference library for the council members on the piano nobile.

The LCC Historic Buildings Committee, under the initial direction of C. R. Ashbee (also responsible for the conservation of Chipping Campden and Jerusalem), supported the Survey of London, an unparalleled history of a great city, which served as a historical record and a tool for preservation. The Survey, unlike the Ministry of Works or SPAB, always appreciated Georgian buildings.

The LCC acquired historic places for preservation, such as the Geffrye Museum in Shoreditch (1906) or Trinity Almshouses in Mile End, and systematically photographed 18th-century buildings. The Historic Buildings Committee came into its own after the Second World War, when listing of historic buildings was introduced. It was an unlikely part of the LCC Architect’s (not Planning) Department, especially when Walter Ison (1908–97), an architect-pupil of Verity and historian of Bath who first moved to preserve Spitalfields in 1952, and then Ashley Barker (an AA-trained architect who instigated the preservation of Notting Hill) became successive Surveyors of Historic Buildings.

In 1954, Francis Sheppard (1921–2018) became general editor of the Survey of London, enhancing its scholarly calibre with volumes on Georgian Soho, St James’s, Covent Garden and the Grosvenor estate. They provided a strong research underpinning for proactive preservation. The committee itself was given clout by the co-option of outside luminaries, such as Summerson, Betjeman and Osbert Lancaster. It tipped the balance towards the preservation of whole swathes of London’s historic fabric. The 1967 Civic Amenities Act, which made listed-building consent for demolition mandatory, halted the destruction from after 1970. No significant Georgian buildings have been demolished in London during the past 55 years.

London has never been this quiet in 2,000 years — here's what it looks like, and what we can learn

In all of its 2,000-year history, it seems unlikely that the City of London has ever stood so silent as