The great houses of The Strand, 'London's Golden Mile' that 'helped shape England’s architectural identity’

A scheme to pedestrianise parts of The Strand is throwing light on the road’s gilded history, finds Jack Watkins.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

‘Leet’s all go down the Strand,’ cries the Edwardian music-hall song, hailing it as ‘the place for fun and noise’. In the 1890s, it had more theatres, music halls, pubs and smoking rooms than any other street in London. However, more recently, it’s been just another traffic-dominated thoroughfare, more noted for its poor air quality. In 2019, it was the first in the capital to breach annual legal limits for nitrogen dioxide.

Now, however, Westminster City Council has begun a £32 million programme to pedestrianise the area around St Mary le Strand and King’s College, as well as creating a two-way traffic system on the Aldwych. The council hopes it will transform ‘this historic gateway to the West End into a world-class and contemporary traffic-free public space’.

How historic a gateway it was is the focus of Manolo Guerci’s sumptuously illustrated new book, London’s ‘Golden Mile’: The Great Houses of the Strand, 1550–1650. Although the street’s name arose from its original use as a bridle path alongside the Thames, according to Guerci, by the 16th century, it was distinguished by ‘a virtually uninterrupted line of majestic riverside mansions’, owned by aristocrats and courtiers, and operating as a de facto substitute for Whitehall, after the Tudor monarchs established a permanent Court in London.

The Strand, just over three-quarters of a mile long, extended from Temple Bar to the Charing Cross monument (destroyed in 1647), and operated as a channel of communication between the City and the Inns of Court to the east and Whitehall Palace and Parliament to the west. Yet, writes the author, these unofficial ‘palaces’ lacked the urban appearance of their European equivalents. Whereas two of the 11 were on the north side of the Strand, those on the south side faced the river. Several were approached from the Thames and entered via water gates that opened onto formal gardens leading up to the houses. Guerci reports they created a rus in urbe effect akin to an Italian villa surbana.

Many of the architects and craftsmen employed on the design of the palaces also worked on their patron’s rural estates. By their centrality, Guerci argues, the Strand palaces ‘helped shape England’s architectural identity’. Combining features of English vernacular with Continental influences, he says, enabled them to reach unprecedented levels of sophistication that ultimately gave rise to a truly English style.

Working his way east to west, Guerci has given each house its own chapter, the main focus being on the period between the 1550s and the end of the English Civil War in 1651, after which many of the great houses began to decline. Re-creating their histories has not been easy. As the author says, even most of the buildings that replaced the Strand palaces in the 17th century have themselves now been demolished. Records of the properties are scattered and plans and contemporary drawings are scarce.

Even so, via meticulous research, the author has pieced together detailed stories. Some of the names associated with these properties resonate through time. Essex House, the most easterly of the palaces, and the first to be seen when approaching London by the Thames, was owned by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester (at which time it was known as Leicester House), the great favourite of Elizabeth I. The original palace was built by the Bishop of Exeter in the early 14th century, but Dudley rebuilt and improved the complex, and it was much visited by the monarch.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

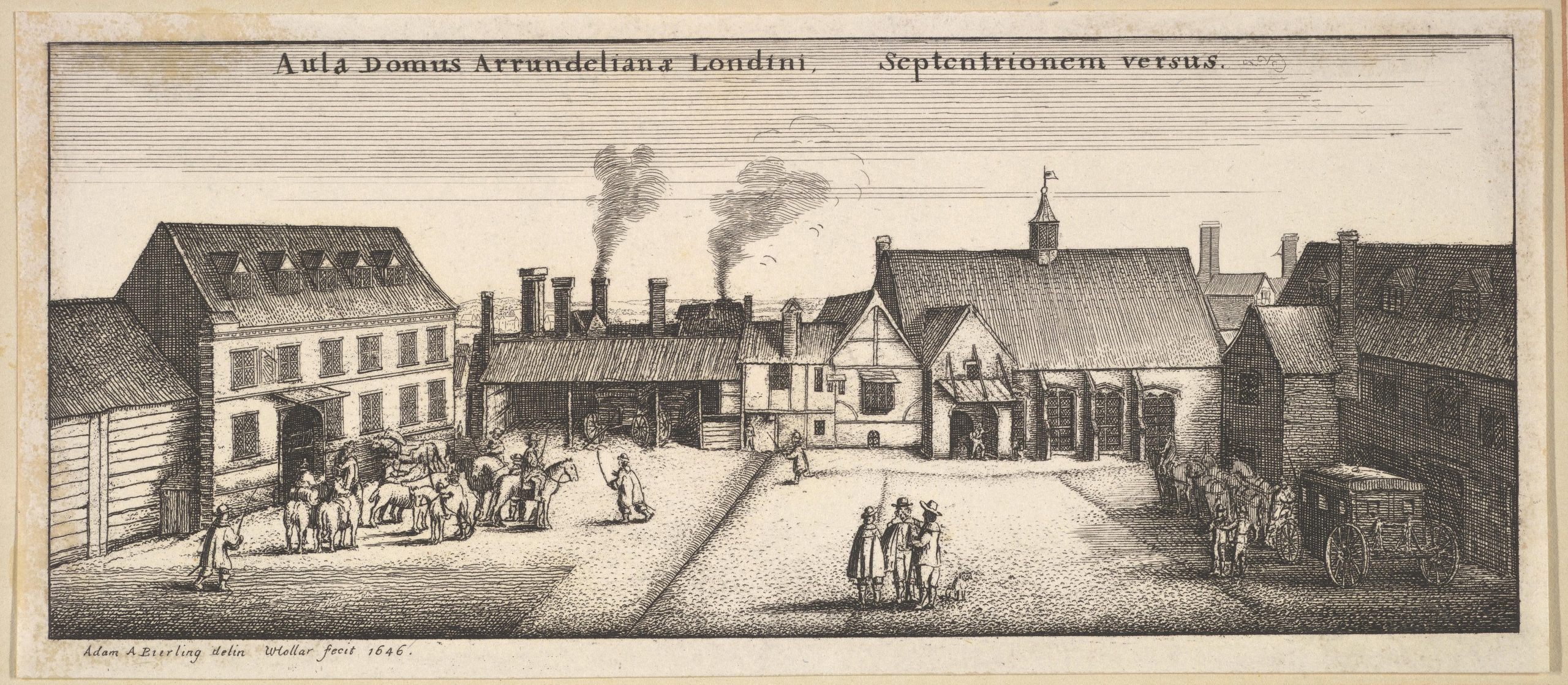

Next to it, the tower of Arundel House, previously an inn of the Bishops of Bath and Wells, was reputedly where Wenceslaus Hollar, the draughtsman and etcher, whose riverside drawings are a vital feature of the book, produced some of his panoramic views of 17th-century London. Hollar was in the employ of Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel, who transformed the house from 1616. Not only did it contain his vast collection of paintings, Inigo Jones was employed in the design of what is reputed to be England’s first garden of antiquities, a tantalising glimpse of which is provided in the background of a portrait of the Earl, painted in about 1627.

This terraced, open-air museum, displaying statues, inscriptions and architectural carvings, was emulated by Howard’s great art-collecting rival George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, further down the Strand at York House. As do many of the other palaces, York House looked towards the river, with rented tenement properties fronting the Strand highway. The memory of its most famous occupant lives on in the road names (Villiers Street; Buckingham Street) long after the house’s demolition in the 1670s.

Here, also, is a precious relic from the Golden Mile era, the rusticated York Watergate, built in about 1626. Today, it serves as a monument marking the former north bank of the river, more than 100 yards away from that of today, after the completion of the Embankment in 1870.

The latter, together with the cutting through of Northumberland Avenue, led to the demolition of the last of the great Strand palaces (and the nearest to Whitehall), the vast Northumberland House, in 1874. By that time, almost every architect of standing, as Guerci says, from Robert Adam to Charles Barry, had passed through its doors. The huge Coade stone lion, the crest of the Percys, on its frontage was saved and removed to their Syon estate.

Somewhere between the overbearing Regent Street and tacky Oxford Street, the Strand and its side streets still reward exploration. The Savoy Chapel lurks within the shadows of The Savoy hotel as the last surviving portion of the Savoy Hospital. There are still three theatres (the Savoy, the Adelphi and the Vaudeville), with the Lyceum and the Aldwych theatres close by. The slender spires of St Mary le Strand and St Clement Danes resemble elegant galleons floating down the highway.

Close by, the arches and courtyard of Somerset House, a grand, purpose-built office development designed by William Chambers in the 18th century (and now the home of the Courtauld Gallery), perpetuates the name and memory of the original palace, built by Protector Somerset from 1547. If the pedestrianisation taking place directly in front of it helps the Strand recover some of its former lustre, that is to be welcomed.

The story of Old London Bridge, the iconic landmark which vanished from the capital's skyline

Important new discoveries illuminate the form and history of the houses that lined one of London’s most celebrated lost landmarks.

The medieval engineering strokes of genius that led to the building of Old London Bridge

Medieval bridges were marvels of engineering, given the technology available at the time — and nowhere more so than in the

Curious Questions: Did a double decker bus really jump over Tower Bridge?

London's most famous bridge is 125 years old in 2019, but for all the marvellous facts there's only really one

The Athenaeum: Ancient history, old rivals and a recent revival for the old Carlton House haunt

One of the grandest Regency clubs in London has undergone a revival in recent years. John Goodall looks at the

Jack Watkins has written on conservation and Nature for The Independent, The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph. He also writes about lost London, history, ghosts — and on early rock 'n' roll, soul and the neglected art of crooning for various music magazines