Westminster Abbey: 1,000 years of coronations, from King Harold and William the Conqueror to Elizabeth II and Charles III

The setting of Charles III’s crowning in Westminster Abbey in London lends grandeur and history to this great ceremony. John Goodall considers the evolution of this remarkable building and its role in celebrating the authority and antiquity of the monarchy.

Westminster Abbey first became our coronation church almost by accident nearly 1,000 years ago. The last Anglo-Saxon king of the English, Edward the Confessor, had a particular fondness for Westminster — then a peaceful spot outside London — and not only created a palace for himself on the Thames here, but also patronised the ancient monastery beside it, rebuilding the church in a new and monumental idiom of architecture inspired by Roman example. He died in this palace and was laid to rest before the high altar of his Abbey on January 6, 1066. The Bayeux Tapestry shows his funeral procession entering the church as a workman erects a final weathercock on the roof.

Taking advantage of the funeral gathering, Earl Harold Godwinson was acclaimed King and crowned in the same church on the same day. It was the first such ceremony ever held at Westminster. Nevertheless, it ensured that, when William, Duke of Normandy, defeated and killed Harold at the Battle of Hastings several months later, he, in turn, sought coronation in the same building.

Things did not go well.

The ceremony took place on Christmas Day 1066 and was a harbinger of the brutality of Norman rule. Mistaking the cries of acclamation in an unfamiliar tongue for treachery, the guards began sacking the surrounding houses.

According to the 12th-century account of Orderic Vitalis, amid the ensuing chaos, the newly-annointed monarch, possibly for the only time in his life, lost his nerve and sat trembling on the throne.

It was on the strength of these calamitous events in 1066, that Westminster Abbey successfully secured and formalised its role as the coronation church of the English kings for centuries to come.

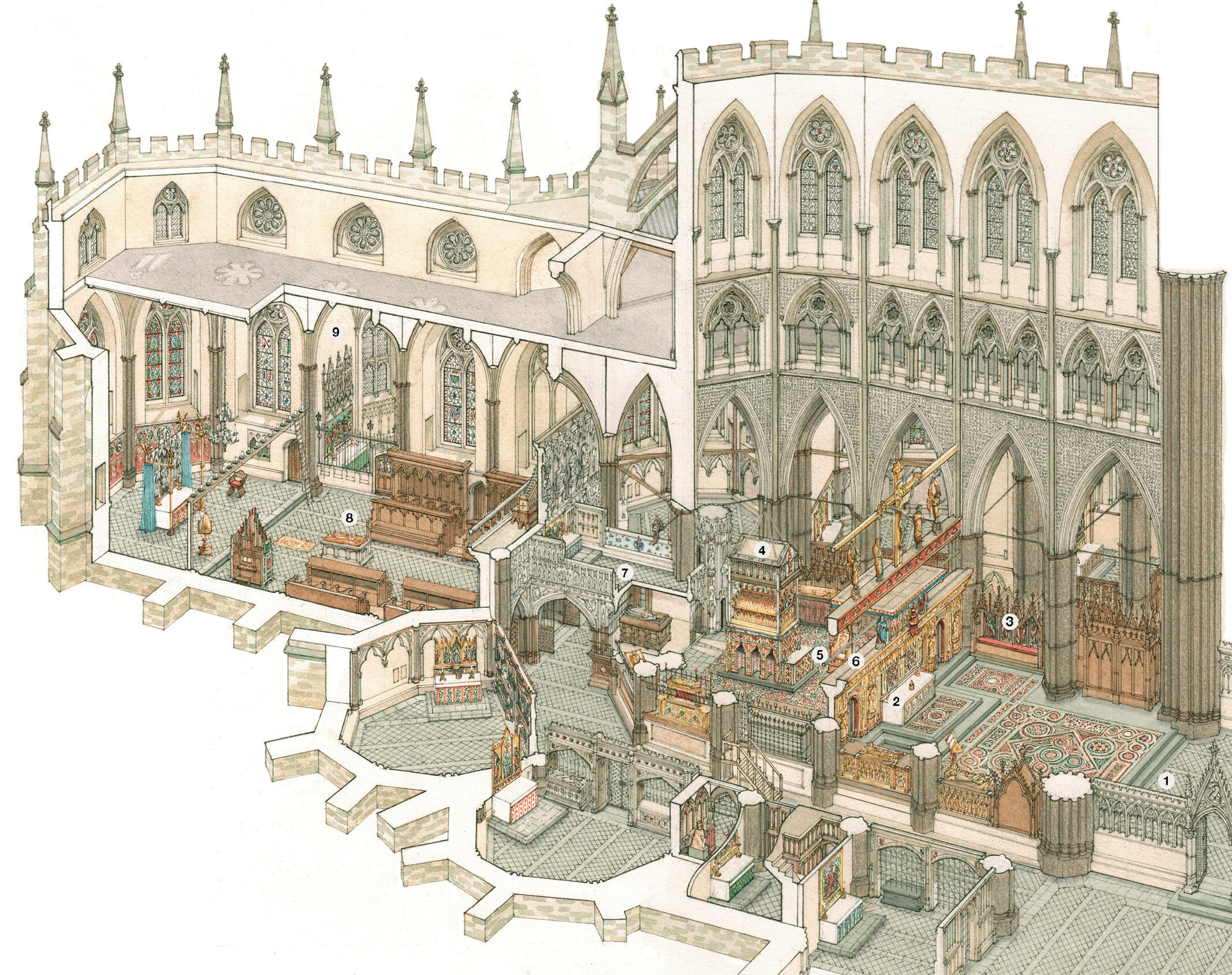

The east end of Westminster Abbey in 1500

The crossing, where the temporary coronation stage was erected, is partially visible to the extreme right (1). From this, steps led up to the sanctuary with its Cosmati pavement and the High Altar (2), backed by the 13th-century Westminster Retable. To the right is a four-part seat or sedilia used by the clergy celebrating mass (3). The Cosmati pavement extended into St Edward’s Chapel, with the Confessor’s shrine (4) encircled by royal tombs. At the end of the coronation service, the regalia were deposited on the attached altar. The usual sedilia for this altar was St Edward’s Chair (5). Dividing the chapel from the sanctuary is a reredos completed by the Abbey mason John Thirsk in 1441 (6), which screened the shrine from the choir. Henry V’s Chantry Chapel (7), also designed by Thirsk in 1438, created an internal porch to the 13th-century Lady Chapel (8). The form of this Lady Chapel—replaced from 1502–03 by what is familiarly known as Henry VII’s Chapel—can be reconstructed from previously unrecognised fragments at vault level. Opening off it is the St Erasmus Chapel (9). The position of the altars in the radiating chapels is inferred from extant fittings and decoration. Overall, this drawing illustrates the way in which colour—in glass, paintings and furnishings—was used to focus attention on liturgically important spaces in what was otherwise a cool, two-tone interior of Reigate stone and Purbeck Marble.

The process was driven forward by a formidable succession of 12th-century abbots, who, with the support of Henry II (then locked in conflict with Thomas Becket), also began to promote the sanctity of Edward the Confessor. The growing importance of the Abbey was naturally reinforced by its proximity to Westminster Palace, which was gradually emerging as the seat of the royal administration. It was distinguished architecturally from the 1090s by a leviathan hall that came to accommodate a fixed throne of stone, the literal seat of royal authority in England.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Our earliest detailed description of an English coronation — that of Richard I on September 3, 1189, by the monk of St Albans, Roger of Wendover — illustrates the intertwined roles of the Palace and the Abbey. On the morning of the ceremony, a procession of nobles and clergy conducted the King from the door of his ‘inner chamber’ in the former to the ‘high altar’ of the latter. Woollen cloth carpeted the route and the coronation regalia were carried in order of importance — a linen coif, spurs, sceptre, rod, three swords, a large board bearing vestments and finally ‘a golden crown great and heavy and adorned on all sides with precious stones’. The King himself followed beneath a silk canopy.

This display of the symbols of royalty made it clear what the King was assuming in the coronation ritual, an event invisible to most within the confines of Edward the Confessor’s church. It was, indeed, the only public outing that the regalia received because, after the ceremony, the King ‘put on a lighter crown and vestments, and so crowned came to breakfast [in Westminster Hall]’. These two processions, the exchange of regalia and the palace celebrations, remained central to the coronation ceremony as it subsequently evolved. Sections of the processional carpet — latterly made of blue ray — were claimed afterwards as perquisites.

In the early 13th century, Westminster Abbey found a crucially important new patron in Henry III. Devotion to his ancestor, Edward the Confessor, and a sense of competition with the resurgent power of the rival Capetian kings of France, prompted him to reconstruct the Abbey on the grandest scale from 1245. Among the points of architectural reference for the new building was the High Gothic coronation church of the French Kings, Reims Cathedral. Indeed, it’s strongly suggestive of a direct link that the mason in charge at Westminster was called Henry ‘of Reynes’.

Henry III’s new abbey church was taller and more opulently detailed than any other English great church. The main elevations made use of different coloured stones and were encrusted with carved decoration (Country Life, December 15 and 22, 2021). Craftsmen were brought from Rome to lay pavements in mosaic and semi-precious stone. Their so-called Cosmati work pavement extends across the sanctuary in front of the high altar and into the chapel beyond it, where a new shrine to Edward the Confessor was erected. The shrine itself and several surrounding tombs, including that of Henry III, were also decorated in Cosmati.

In certain details, the choir of Henry III’s church seems to have been designed with the ceremony of coronation in mind. The triforium gallery, for example, is exceptionally large, presumably to accommodate spectators, and the piers of the crossing are strikingly slim in order to open out views through the building (Fig 2). It is unlikely to be a coincidence that the design of the Cosmati floor in the sanctuary defines a central area in front of the high altar, an ideal spot for the King to be anointed.

By these changes, Westminster Abbey was not only splendidly renewed as a theatre for coronation, but it simultaneously became the mausoleum of England’s kings and the shrine of their royal saint and ancestor, Edward the Confessor. Uniting these functions in one place right beside the seat of the royal administration in Westminster Palace was exceptional in contemporary Europe. The Capetians, by contrast, were crowned at Reims (where the implements of coronation were divided between ecclesiastical institutions), had their mausoleum at St Denis and displayed their relic collection in the splendid interior of the Sainte Chapelle on the Isle de la Cité in Paris (which was also the seat of the royal administration).

Only the choir, transepts and eastern nave of the new abbey church at Westminster were completed during Henry III’s reign. They were first used for a coronation by his son, Edward I, in 1274, when the crossing had to be boarded over to tidy up the interior. It would be more than a century before the awkward abutment of the Gothic and Romanesque elements would be resolved by rebuilding. For this period, the main entrance to the church probably moved from the nave to the splendid north transept (Fig 3).

More important for the coronation — and completely conventional within a great church — was the creation of a gated liturgical enclosure inside the main volume of the building. At Westminster, this comprised the Confessor’s Chapel with its shrine beyond the high altar, the sanctuary to the west of the high altar, the crossing and the monastic choir, which occupied the first bays of the nave. This enclosure was ringed with high screens, furnishings and monuments, which were incrementally developed throughout the Middle Ages.

The use of these spaces in a coronation is described in the so-called Fourth Recension, a version of the liturgy first securely known to have been used to crown Edward II on February 25, 1308. Its directions or rubrics — augmented in the late 14th century — describe a ‘pulpitum’ or stage that was to be set up ‘near the four high pillars in the cross of the church’, with steps rising to it from the choir and descending towards the high altar. The structure was to be covered in carpets and cloth of gold. From about 1400, the area around the high altar was also dressed in tapestry for the coronation, the most fabulously expensive of all surface coverings.

On arrival in the church, the King was presented by the Archbishop of Canterbury to his people each side of the stage and acclaimed before being led to the high altar, to make an offering of gold. He then briefly prostrated himself on the floor, which was spread with carpets and cushions, before taking a seat on the sanctuary to hear a sermon.

What followed was laden with symbolism. In very abbreviated form, the coronation oaths were then taken at the high altar, after which the sovereign took off his outer garments and was anointed. The regalia, having been brought in procession to the Abbey, were laid on the high altar and the King was vested. He must have stood to put on such things as the tunic or colobium, although he is usually depicted receiving the crown seated. The history of this regalia is now beyond rescue — all bar one item being destroyed in 1649 — but there were clearly traditions that linked it to the figure of Edward the Confessor, reinforcing the connection of the living monarch with this legitimising and saintly ancestor.

The King then offered his sword to the altar, which was immediately redeemed, and was afterwards conducted to ‘a lofty throne’ on top of the stage in the crossing where he could ‘be clearly seen by all the people’. For Edward II’s coronation, this structure — probably resembling the 1370s cathedra at Durham (Fig 4) — is elsewhere described as incorporating seats for the King and Queen and of being high enough for a mounted knight to ride beneath it. Enthroned on this, he received the homage of his nobles.

The Queen’s coronation followed the King’s in similar, but distinct, form. She received the homage of the women present and her throne was pointedly lower than her husband’s. Next, a Mass was celebrated, after which the King and Queen descended from their high thrones and were conducted past the high altar to the shrine of Edward the Confessor. Here, they were divested of all their regalia and their crowns were placed on the altar of the shrine. Then, wearing lighter crowns and with their sceptres only — which were later collected by the Abbot of Westminster, the custodian of all the regalia — they processed back to Westminster Hall for breakfast.

Such are the rubrics, but other accounts of Edward II’s coronation suggest a chaotic event. One anonymous eyewitness describes the press of people causing the partial collapse of the coronation stage and the death of a knight. The behaviour of the notorious favourite, Piers Gaveston, meanwhile, incensed several important guests. Royal accounts additionally reveal that the enthronement took place in a huge, temporary hall within the Palace. Its arched throne recess — presumably resembling that which survives at Knaresborough Castle, North Yorkshire (Country Life, January 17, 2008) — incorporated a gilt effigy of the King, a means of making his likeness visible to everyone. It gives some sense of the numbers attending that 14 subsidiary halls were erected for the occasion, as well as 40 ovens to prepare food. Ostentatious and prolific consumption was essential at such an important royal event.

In the late 14th century, Richard II further enriched the architectural setting of the coronation, pressing forward the construction of the Abbey nave and re-roofing Westminster Hall in its present, magnificent, form. He also had an image of himself in regalia painted on his stall in the choir (Fig 1).

Ironically, the King who first used these spaces for his coronation, however, was the man who deposed him, Henry IV. This ceremony in 1399 was necessarily organised with particular care. To dignify the usurpation, not only was discovery made of an ampule of oil supplied by the Virgin herself, but an existing piece of furnishing in the Abbey was pressed into new service for the act of anointing, probably for the first time. This was St Edward’s Chair (Country Life, May 29, 2013), containing the Stone of Scone, upon which Scottish kings were inaugurated. A trophy of war, the stone, together with the Scottish crown and sceptre, was gifted to the Abbey in 1298 by Edward I. It was incorporated within a special seat for priests celebrating Mass at the shrine altar of Edward the Confessor and the chair has subsequently been used in every coronation.

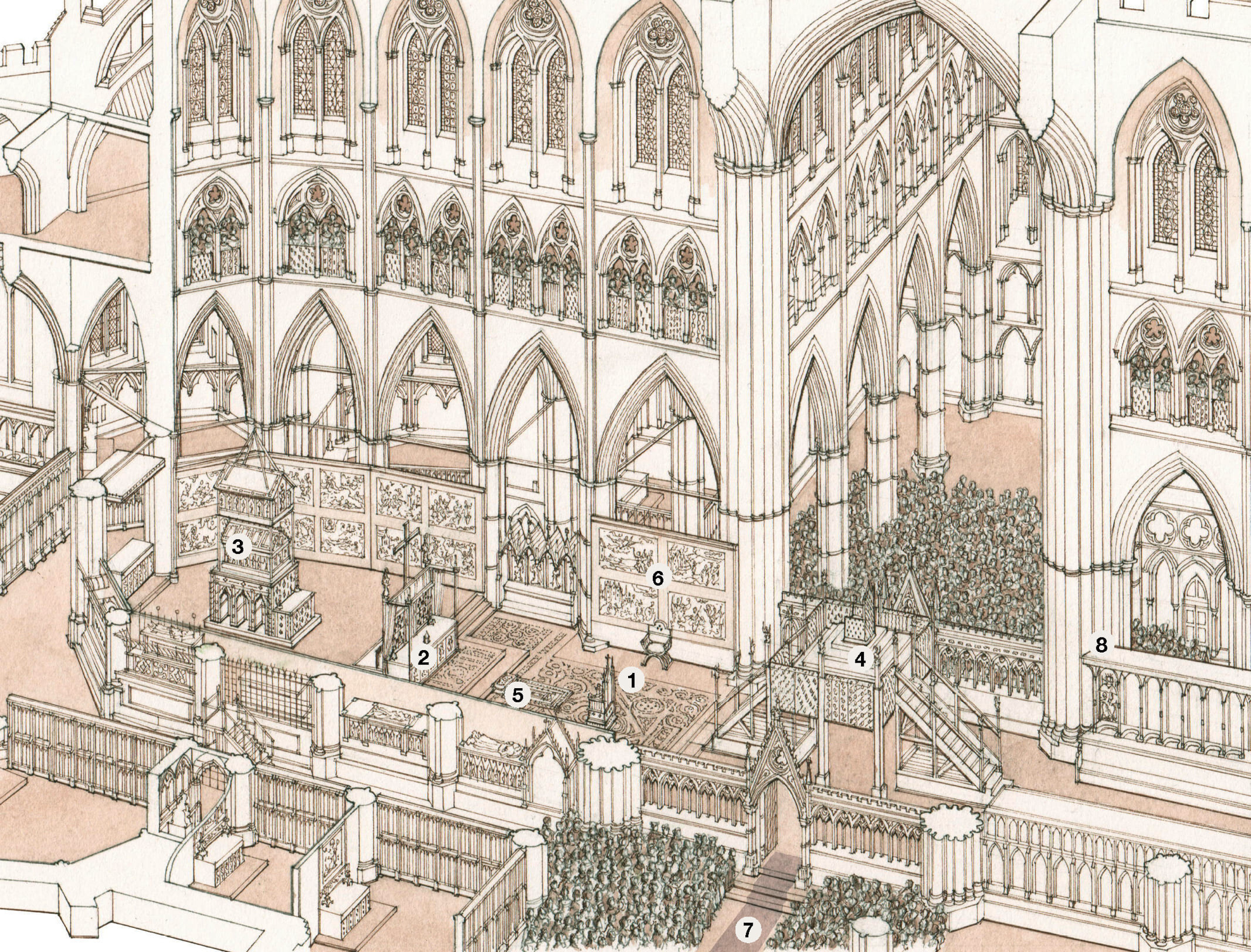

Westminster Abbey on coronation day in 1399

Westminster Abbey as prepared for Henry IV’s coronation in 1399, the first in which St Edward’s Chair (1) is securely known to have been used for the anointing. Note the open plan of the interior between the High Altar (2) and shrine (3). The King was shown to his people on each side of the crossing stage, but climbed up onto an elevated throne above it (4) to hear the Coronation Mass and to receive homage. According to the rubrics of the coronation liturgy, a carpet and cushion were laid where the King abased himself on the sanctuary floor (5). From the late 14th century, the church interior was almost certainly dressed with tapestry, then a novel and stupendously expensive type of wall covering (6). Entrance to the choir enclosure was carpeted in wool (7) and, when the nave was under construction, was probably through the north transept. Richard II’s portrait dignified the first north stall (8), the conventional position of a bishop’s throne or cathedra.

Another innovation made at about this time was the use by peers of so-called parliamentary robes and fur-lined caps of estate. These caps were carried in procession to the coronation and then put on collectively after the crowning, a theatrical flourish first recorded in the 1440s sculpture of Henry V’s Chantry in the Abbey.

From the late 15th century, there is a growing volume of documentation on individual coronations, most of it compiled by heralds. These suggest the outward forms of the ceremony remained remarkably consistent. Such changes as it underwent generally emphasised its magnificence, one such being the gradual enrichment of the robes worn by peers. Not only did they adopt small crowns or coronets, but, by 1626, robes lined with rich fur.

The Restoration in 1660 and the need to revive the traditions of monarchy prompted a further outpouring of antiquarian study and analysis of the ceremony. The herald Francis Sandford set a new standard in this regard with his sumptuously illustrated account of the coronation of James II and Queen Mary, published in 1687 (Fig 5). From this point forward, the physical appearance of Westminster Abbey as a theatre for coronation — its interiors transformed by temporary viewing galleries — is easy to reconstruct. Such imagery underlines the degree to which every coronation is a reinvention of tradition. Over the coronation weekend in 2023, we will all be able to enjoy the next step in its evolution.

Curious Questions: What is it like to sing at a royal coronation in Westminster Abbey?

The choristers at the Coronation are now in their eighties, but recall vividly the day they sang for The Queen,

Westminster Abbey: How the nation's coronation church has touched our lives for 1,000 years

In anticipation of The Queen’s Jubilee Year, Country Life had the opportunity to photograph the majestic interiors of Westminster Abbey,

Jason Goodwin: 'It is up to each of us to keep our heads, do what is right and avoid evil'

A timely pilgrimage to Westminster Abbey sees Jason muse on the notions of sovereignty that haven't changed since the days

The story of the Queen's Diamond Jubilee Galleries, Westminster Abbey's first major addition in 250 years

The architectural choices behind the recent additions to Westminster Abbey mark them out as a radical departure. John Goodall admires

Westminster Abbey: History, power, tourism, and its status as 'the single greatest and most eclectic museum of sculpture in the world'

Westminster Abbey has been at the heart of national life since the Middle Ages. In the second of two articles,

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.