Hall Place, Hampshire: The fabulous house where the Duchess of Cornwall spent her idyllic childhood summers

Hall Place in West Meon, Hampshire, is currently the home of Michael and Claudia Langdon. Yet for many years it was owned by the grandparents of HRH The Duchess of Cornwall. The house, so well known to The Duchess in her childhood, was specially chosen by her for coverage in her guest-edited issue of Country Life. It is revealed in a new light by fresh documentary research, as John Goodall reports. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In late May 1944, Country Life published a pair of articles on Hall Place, which stands in the intimate chalkland valley of the River Meon. This ‘delightful house’, begun in the early 18th century, had been remodelled on the eve of the Second World War by the architect Ernest Barrow. The accompanying black-and-white illustrations show a series of stylish interiors with chintz-covered furniture and eye-catching paintings and sculpture. They represented, in the eyes of the article’s author, Christopher Hussey, ‘the last years of civilised life as enjoyed during the 1930s’.

The renovation of the house had been undertaken for its most recent owners, the Hon Ronald Cubitt and — the real figure behind the project — his wife, Sonia, née Keppel. Sonia was the daughter of Alice Keppel, the sociable and cosmopolitan mistress of Edward VII. The Cubitts were divorced in 1947, but Sonia thereafter continued to live at Hall Place, lavishing care on the property. As a consequence, the house became well known to the Cubitts’ granddaughter, Camilla Shand, now The Duchess of Cornwall.

Hall Place remains immediately recognisable today as the house occupied by the Cubitts and illustrated in 1944. Nevertheless, it has also changed both superficially — with regard to its decoration and furnishing — and in more important respects. It’s a happy moment, therefore, to revisit this building, reconsider the story of its development in the light of fresh documentary research and reveal in the process the depth, complexity and interest of its architectural history.

The Duchess on Hall Place today:

‘Hall Place is lovely, but it does look very different now. In our day, there was a long entrance passage and, on the first floor, a huge refectory table that ran the length of the room. My grandmother had a wonderful collection of blue john on that table, as well as an enormous bowl that was always filled with lavender. For me, Hall Place has a special appeal because it’s where we spent two or three weeks every summer when we were children and for years after, until my grandmother’s death in 1986.

'The minute we walked in the door, we felt excited to be there. We never kept ponies there, although Gyles Brandreth will swear that he once met me there wearing riding breeches and smoking a woodbine — I’ve never smoked a woodbine in my life! My grandmother — whom we loved — wanted us to learn to sail, so we frequently did courses on the River Hamble and my sister, Annabel, often managed to capsize the boat! There is something magical about the house — it’s been a joy to revisit Hall Place and I will always remember our happy days there.’

The Domesday survey of 1086 describes the manor of West Meon as a possession of the church of Winchester. Ownership of this manor — valued at more than £35 in 1291 — was subsequently vested in the prior and community of Benedictine monks that served St Swithun’s Cathedral, but, for periods, it was also effectively leased to the bishop, who probably managed the land from his neighbouring manor of East Meon. It’s possible, therefore, that no substantial medieval manor house ever existed here.

Nor did the post-Reformation owners of the property, the Earls of Southampton, have any need to build at West Meon; their resources were initially focused instead to the south of Hampshire, at Titchfield. By 1664, the manor had been bought from the 4th Earl by one Thomas Neale, who, in 1677, sold it to a London lawyer, Isaac Foxcroft, of Inner Temple.

Foxcroft’s purchase of West Meon was evidently part of an attempt to set up his family as landowners in Hampshire and, in 1690, he enjoyed sufficient local interest to be appointed High Sheriff of Southampton. The longstanding assumption has been that he built the present house, but his will of 1698 strongly suggests otherwise. It makes no mention of West Meon and underlines instead Foxcroft’s strong London connections: he is described as being ‘of Marylebone’ and, after an unusually long and pious preamble, requests burial in the same grave as his ‘most honoured father’ in the church there.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The will also speaks of Foxcroft’s remarkable wealth. He promised outright gifts of £10,000 and £7,000 respectively to his daughters Elizabeth and Dorothy when they either married or reached their 21st birthdays, as well as giving valuable rental property in St Giles in the Fields to his younger son, Isaac. To his eldest son, Henry, meanwhile, he bequeathed his law books and all his land ‘in the county of Southampton’.

It was Henry, therefore, who presumably established the new family seat at West Meon on the plot at the edge of the village once occupied by the medieval manor house (whether or not such a building still survived); hence the name Hall House or Hall Place. In the fashion of the moment, Henry built the rectangular brick box five window bays wide and with a hipped roof that forms the heart of the present house (Fig 1). It’s possible that the original services and kitchen to the house were from the first incorporated within a low wing and court to the left (east) of the main front. Alternatively, they may have been accommodated in the cellar.

The interior was on a relatively small scale, with a central staircase hall (Fig 3) running through the house and two rooms to each side of it on both the main floors. There were formal rooms on the ground floor, bedrooms above and — presumably — servants’ rooms in the attic (Fig 5). For ease of construction, the chimney flues were clustered together in two stacks, one to either side of the building. These served fireplaces set in the angles of the rooms.

In contrast to this relatively modest interior, the main front was smartly finished. There are small masonry projections articulating the angles of the original building, a string course externally demarcating the two main floors, rubbed brick window lintels and a chequerboard pattern in the walls. This last detail, made using bricks burnt black in the kiln, must have been time consuming to create and was not consistently adopted when the building was subsequently extended.

As a further enrichment, the front incorporates a quantity of sculpture. There are numerous fox heads, a clear reference to the family name, and an ornate monogram in the doorcase (Fig 2). This has long been believed to combine the letters I, E and F in reference to Isaac and E_ (for his wife, whose name was formerly unknown) Foxcroft. In fact, his wife was Dorothy (a daughter of Sir Henry Johnson of Blackwall, Middlesex) and the whole more convincingly reads as the letters H and E bound together with an F to represent the marriage of Henry Foxcroft and Ellen Wittrong. This probably took place in about 1704–06, the former date being when Ellen reached the age of 21 and the latter when Henry began acting in court cases on behalf of his younger brother, evidence that he had come of age.

Echoing his father, Henry had aspirations to local office and, in 1710, served both as High Sheriff and entered into politics, campaigning for the seat of nearby Petersfield in the Tory interest. He never entered Parliament, however, and his will, proved in 1738, shows he was a far poorer man than his father. Even so, he had the resources to own a coach, which he bequeathed, with its horses, to his wife.

The manor and house descended in the Foxcroft family until 1773, when the last member of the family — another Henry — sold them for £5,350 to one Charles Rennett. It was possibly during Rennett’s occupation that Hall Place underwent its first major adaptation, with the creation in its present form of the east wing of the building. By this date, thanks to changes in entertaining fashions, there would have been a perceived need for larger reception rooms and this addition provided ample accommodation for one at ground level (now the dining room).

Some elements of the garden must also have been established by this date, although the bones of the design could date back to the construction of the house. These probably included a large formal compartment to the rear of the building and a turning circle in front. A straight path through a wood to the west of the house led to a small garden building, also, presumably, an 18th-century creation.

Sometime after 1802, title to the manor of West Meon passed to John Dunn, Rennett’s former steward, and then by marriage into the Aubertin family. Confusingly, Hall Place was sold independently and in sequence came into the possession of Joseph Sibley (by 1828), his widow, Frances (who died aged 95 in 1849), and then their daughter, Elizabeth. In 1873, Elizabeth, by then also in her nineties, tried to pass it to a niece, Harriet Smyth. Harriet, however, agreed the following year with her husband to sell the house and its associated property for £4,500 to a local clergyman, the Revd John James Digweed.

In 1901, Hall Place was sold yet again, to Charles Harris, for £5,000. It must have been Harris who soon afterwards instigated the complete reorganisation of the building with a new west wing, which is shown in the 1909 Ordnance Survey. The wing again provided larger rooms, including what is now the drawing room (Fig 7). This was integrated into the plan of the house by punching through the 18th-century room divisions at ground-floor level to create a long gallery (Fig 6) to the right of the front door. All the joinery was done in a very convincing 18th-century style and, to the west, the house was provided with a new façade six window bays wide and crowned by a narrow pediment. Some authorities have mistakenly assumed the façade is Georgian.

In the 1930s, the Cubitts renovated the house, but seem to have preserved the fabric much as they had inherited it. More significant were the alterations Sonia made to the garden, which were undertaken in part with the help of the American designer Lanning Roper. These changes cumulatively created a house with three strikingly different prospects. From the north-facing entrance, it overlooks a wide lawn that drops to the river in the middle distance, whereas to the rear it looks up the rising slope of the valley towards a dovecote seat. Lastly, to the west, it faces across a rose garden built in 1947 and up the valley of the Meon across water meadows.

In the mid 1980s, the house was sold to Dru and Minnie Montagu and further changes were made to it by Christopher Smallwood Architects. One playful detail from this period is a doorcase in the service courtyard that is carved with dogs (Fig 8), in evocation of that created by Henry Foxcroft for the front of the house. The Montagus also inserted a new back stair.

The present owners, who bought the property in 2013, have further developed the garden and made sensitive changes to the house itself. Perhaps the most striking of the latter alterations has been the addition of a limonaia, designed by Hugh Petter of Adam Architecture, to the rear (Fig 4). This stands between the two existing wings and is built of Portland stone. One of the challenges of designing this addition was creating an elevation that sat comfortably beneath the slightly awkward six-bay elevation. The satisfying solution has been to create a pair of doors into the building, rather than merely a central entrance.

Hall Place gives the outward impression of being a coherently planned 18th-century country house. On examination, however, it is revealed to be a building that has commanded the affection of a whole series of owners and been repeatedly improved and adapted over the past three centuries. The Duchess of Cornwall, therefore, is demonstrably one among many who have been captivated by its charms.

Camilla's Country Life: How to watch the behind-the-scenes television documentary about The Duchess of Cornwall's Country Life guest-edit

Find out where and how to watch the ITV documentary 'Camilla's Country Life', all about The Duchess of Cornwall's guest-edited

The Duchess of Cornwall's country champions, from a bee master and an equine therapist to The Prince of Wales and Jeremy Clarkson

The Duchess of Cornwall names her countryside champions in the 13 July 2022 issue, which she has guest edited. Among

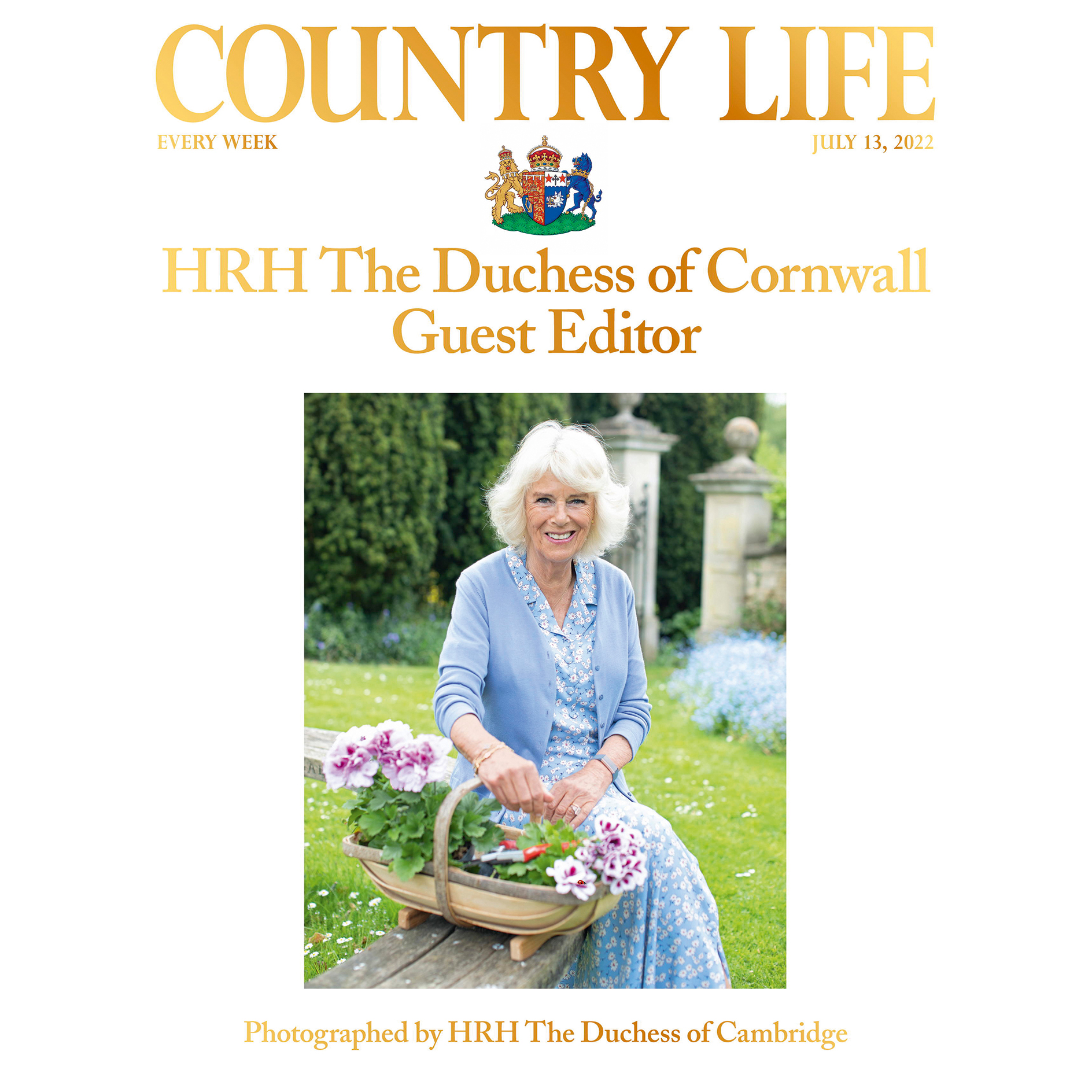

The behind-the-scenes story of The Duchess of Cornwall's guest-edit of Country Life

The 13 July 2022 edition of Country Life, guest-edited by HRH Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, has been a huge effort

Credit: Country Life

What's inside The Duchess of Cornwall's guest-edited issue of Country Life — and how to get your copy

We're thrilled and delighted that HRH Camilla, Duchess of Cornwall, has guest edited the 13 July 2022 edition of Country

The Duchess of Cornwall: ‘I have a profound sense of being at home in the countryside’

In her leader article in the 13th July 2022 issue of Country Life, guest editor HRH The Duchess of Cornwall

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.