Jason Goodwin: Is the answer to finding faith really as simple as "fake it 'til you make it"?

The ancient Ottomans knew the power of repetition to shape the minds of others — something that Jason Good has discovered for himself.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In their swagger days of pageantry and power, when the Ottoman Turks ruled from the deserts of Arabia to the suburbs of Vienna, they recruited into their ranks from the Christian heartlands of their empire. Every year or so, the tribute officer would set out from Istanbul to tour the Balkan highlands, going from one village to the next to select likely looking boys for the imperial service.

The boys, aged roughly between 10 and 15, were taken from their peasant families and marched off to Anatolia, to work on farms and learn Turkish. There were some exemptions: widows weren’t deprived of their only sons and the selectors avoided boys who had ever lived in towns, where their morals might have grown a little crooked.

Born Christian, the boys would convert to Islam by repeating the formula: ‘There is no God but God and Mohammed is his Prophet.’ From then on, the entire machinery of the Ottoman state was open to them, by their merits. They swelled the ranks of the Sultan’s infantry brigades, the infamous Janissaries, and furnished the palaces with gardeners and cooks.

The brightest and the best would enter the bureaucracy, so that a boy born a poor shepherd on a Balkan hillside might find himself acting one day as the Sultan’s Grand Vizier, a man cultivated and urbane, taking decisions that affected the course of history, the fate of nations and the lives of millions inside and without the empire’s far-flung borders.

In matters of faith, I follow the wise old Turks. Critics of the system pointed out that the process of conversion to Islam didn’t appear very deep or very sincere. The Turks believed otherwise, however. A boy’s devotion to the faith might be shallow at the outset, they agreed, but by dint of repetition and practice, true faith would invariably follow.

'I can’t tell you what it all means. I cannot pretend to understand.'

I cultivate my belief on the Ottoman principle. It was a Spanish Muslim, Ibn Khaldün, who said that, although it was always best to be a Muslim, as one might expect, Christianity or Judaism would do as well if Islam wasn’t the local thing. And that’s rather the case down here.

When our boys were small, we lived in a remote, downland hamlet distinguished only by its shepherd’s church of flint and tile. Neither Kate nor I were from churchy families, but, every month, we took advantage of the only entertainment available within easy walking distance.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

We sat in a beautiful building, one so old that, in some countries, it would have been maintained as a national shrine. We sang and we were silent. We listened to the poetry of the King James Bible and mumbled the lines of Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer. Best of all, probably, was that the children saw the grown-ups on their knees and saying sorry.

Over time, it began to sink in. I started to believe in the language and the litany. When I thought about the strength people have derived from their faith, I found I wanted to believe in the life of the world to come. People who do, I’ve noticed, face death with equanimity.

I’m working on the Creed. Some of it is still a stretch, such as virgin birth, and other parts I can wave through like a post-Brexit customs officer. One baptism for the remission of sins? No problem. Have two, if it would help.

I can’t tell you what it all means. I cannot pretend to understand. However, there is a baby and a mother at its heart and he is called the Prince of Peace. That’s a decent start, as the Turks might say.

Jason Goodwin: In memory of Norman Stone, my tutor, guide, world traveller — and friend

Jason Goodwin pays tribute to an old friend and mentor.

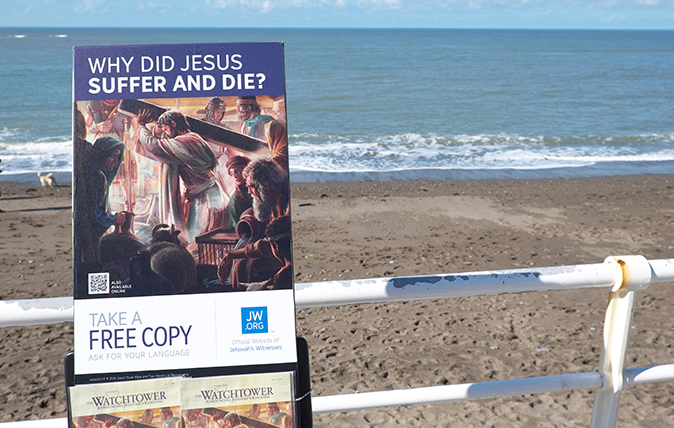

Jason Goodwin: Keeping up with the Jehovahs

'I don’t get into theological debate with them; I simply like to bask awhile in their radiant happiness'

Jason Goodwin: 'On our watch, the natural glories of our island have been atrociously depleted'

Our columnist Jason Goodwin laments the staggering decline of British wildlife and the depletion of our island's natural glories.