Eilean Donan Castle: The property of the Conchra Charitable Trust by Antony Woodward

Despite its medieval evocations, Scotland's most familiar fort was built between 1913 and 1932 over a 200-year-old ruin: the romantic vision of Col. John MacRae-Gilstrap, his architect George Mackie Watson and the mason Farquhar MacRae. Antony Woodward reports. Originally published in Country Life, January 13, 1994.

RETURN TO THE SCOTTISH CASTLES HOMEPAGE

Preposterously picturesque, the castle on the "Island St Donnan" is as indispensable to the Highland tourist industry as haggis-hunting or the Loch Ness monster - and, in its own way, nearly as fraudulent (Fig 1). If anything even more enchanting than the pictures on the postcards and calendars suggest, it faces out onto Loch Alsh where that arm of the sea breaks into Loch Long and Loch Duich, on the principal east-west route across the Highlands to Skye; a supremely strategic site which has been used to defend the west coast since the Vikings were marauding. The original fort was impregnable until Hanoverian frigates blasted the castle and its Jacobite-supporting Spanish garrison to pieces in the uprising of 1719. Thereafter, for 193 years, the shattered shell lay abandoned (Fig 2); the condition it would be in today but for Major John MacRae-Gilstrap (1861-1937), the second son of the MacRae family of nearby Conchra.

Fig 1. The castle and Loch Alsh from the east. The keep was complete by 1928, the rubble causeway by 1932 and the L-shaped south-west range two years later.

The major was a man with a mission: to re-establish himself in succession to three generations of his ancestors as owner and hereditary Constable of Eilean Donan. As second son claiming an office which, according to many historians, was only ever appointment only, it was an ambition which required time, money and perseverance. He obtained the money by his marriage in 1889 to Isabella Mary Gilstrap. The second daughter and co-heiress of Mr George Gilstrap, she was also co-heiress of her wealthy uncle, Sir William Gilstrap, Bt, of Fornham Park, Suffolk, head of the successful malting business Gilstrap Earp and Co. On Sir William's death in 1896, as a condition of inheritance, Capt. MacRae (as he then was) assumed the Gilstrap surname (dropped a generation later) by royal licence. Evidently his new wife was keenly supportive of his plans to re-establish his connection with Eilean Donan; a fact suggested by her eventual provision of some £250,000 for the acquisition and rebuilding of the ruin, and her authorship of the book The Clan MacRae.

The story begins with the purchase of the island and ruin (only) from Sir Keith Fraser of Inverinate in about 1912. Although Particulars of Sale of the Inverinate Estate were available from 1907, and the major was congratulated in a letter from Francis Grant at the Lyon Office in 1910 on securing "such a historical place connected with your family" and advised to hold "a gathering of the Clan to take formal possession" the major's Edinburgh solicitors only acknowledge receipt of his cheque for £2,500 to cover the cost of the purchase on January 24, 1913, soon after which the event was announced to the press. A gathering of the clan was duly held on August 14, 1913, in which the major took possession and hoisted his flag on the castle as "Constable of Ellandonan".

Fig 2. The ruins before restoration. The original castle was shelled by English men-of-war in 1719 and lay abandoned until 1913.

How far the major's plans extended at this stage it is hard to know. In his widely reported speech at the opening ceremony he expressed his hope that "part of [the castle] at least may rise from its ruins". Fortunately the major documented his affairs with military efficiency. Clan information, texts of speeches, invitation lists, accounts and receipts, correspondence between himself and his architect and builder, architectural drawings and newspaper cuttings reveal growing building ambitions - and tell a lively story, whether the major is chivvying newspaper editors for publicity, endeavouring to substantiate his right to assume the title of hereditary Constable, or negotiating a private pew for his family and servants in the local church.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

By September, the clearing of the ruins had begun. The major had secured the services of a local clansman, Farquhar MacRae (a former carpenter), who thenceforward lived on the island, supervising the works, until his death 20 years later. Before departing for the First World War in the proper style of a clan chief (he raised and commanded the 11th Battalion of Royal Highlanders) Major MacRae-Gilstrap, fired with the idea of rebuilding, solicited the advice of Sir Fitzroy Maclean, Bt, of Morvaren - who was restoring Duart Castle - as to a suitable architect for Eilean Donan. A letter written to Farquhar in January 1914 reveals that he had chosen an architect. It was the little-known George Mackie Watson (1860-1948), an Edinburgh man who had worked as assistant to Sir Rowan Anderson on the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and who had worked at the major's estate at Ballimore as well as locally at Conchra. A comment in the same letter is significant: "I am glad you kept the arch formation on the east section of the keep for the architect's inspection. It may suggest something to him..." This indicates that, despite the major's energetic correspondence with museums, antiquarian societies and galleries in pursuit of visual references as to the form of the original fort, his aim in rebuilding was not just one of simple reconstruction.

Fig 3. The MacRae-Gilstrap arms above the portcullis.

Building began after the war. Watson's plans for keep and entrance block, dated January 1918, adhered to an 18th-century plan and profile "Surveyed & deliver'd by Lewis Petit". The roofless, hexagonal well is enclosed within the heavy surrounding curtain wall by a protruding arm, with the rectangular keep at the north-east corner, diagonally opposite an L-shaped block. He extended a small house to the left of the entrance to link up with the keep.

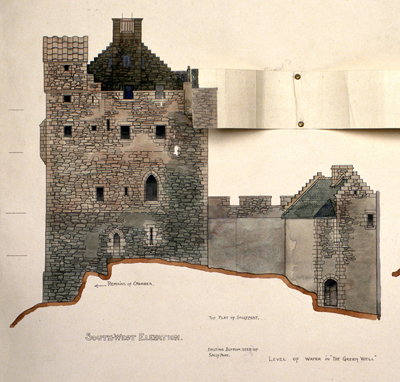

In detail, Watson was consciously Picturesque. He included machicolated bartizans where the well wall joins the main enclosure, a much elaborated entrance gateway with working portcullis (Fig 3), a sea-gate and, despite the exposed situation, unharled rubble walls. For some reason he omitted a pepperpot turret from the south-west corner of the keep (flaps on his drawings indicate his ruminations, Fig 4) and rebuilt only the south range of the L-shaped south-west block. As built, his only obvious deviations from his own plans are the squaring-off of the larger windows, which are arched in the plan.

Fig 4. Mackenzie Watson's drawings show that he first intended to include a pepperpot turret.

Roughly hewn steps lead up from a tiny, rocky courtyard into a tunnel-vaulted Billeting Room (Fig 6) on the ground floor of the keep, with the banqueting hall complete with secret passages and spy-holes upstairs (Fig 5); both are aptly described by John Gifford in Pevsner's Highlands and Islands as "a rubbly Edwardian stage-set for life in the Middle Ages". The aim was to combine modern conveniences electric light and central heating with the honest (non-machine-made) simulation of antiquity: Watson attacked the falsified ageing of a door in 1924 as "Vandalism pure and unadulterated".

Weather and labour problems, and the island site, meant that the building work was beset with difficulty. The Times (July 18, 1932) reported how quarried stones from the neighbouring hills weighing up to 3Ocwt "were dragged by a horse to the shore, and there, at low tide, chained to the bottom of a boat, which, when the tide rose, was rowed over to the castle". Other materials, including hewn oak beams, steel stanchions and green slates from Caithness, arrived by boat. Unfortunately, sea sand was collected locally and mixed, unwashed, into the mortar and concrete, which in recent years has led to structural problems where salts incorporated into the concrete have corroded embedded steel beams.

Fig 5. The Banqueting Hall on the first floor of the keep has secret passages and spy holes.

By April 1926, progress was advanced enough for permanent access from the mainland to be considered. A year later Mr J. Findlay of Ardelve quoted £1,012 13s 6d "for road and bridge only", yet photographs in the Inverness Museum indicate that there was still no bridge by 1931 (although the keep and entrance range were complete). The prettily curved, three-arched rubble causeway was eventually built in 1932.

The castle's official opening on July 22, 1932, was widely reported by the press. Many additions came only after the official opening, including the complete south-west range, the finishing of the well-wall, stairway railings, roofing details and the walls supporting the curved roadway to the main entrance (the drawings of which are signed "A. R. Munro, Clerk of Works, 25th Jan 1934". He must have taken over after Farquhar's death four months before the official opening). Shortly after completion the south-west face of the keep was harled in an effort to reduce the damp caused by prevailing Atlantic wind hurling water from the stone spouts back against the wall.

Fig 6. The Billeting Room on the ground floor of the keep. The barrel-vaulted ceiling - 2 1/2 ft. thick at the centre - caused considerable problems during construction.

How was the rebuilding received? "I was horrified and repelled by the ruined picture which obtruded itself on the outraged surroundings, the remains of the castle being in the throes of a rebuilding which must permanently disfigure the landscape ... one can only marvel at a taste which finds any satisfaction in transforming a picturesque ruin which harmonizes so completely with its surroundings into a permanent blot on the landscape...", wrote M. E. M. Donaldson in Wanderings in the Western Highlands and Islands in 1923, although such feelings ran counter to most. When Major, by then Lt-Col., MacRae-Gilstrap died in 1937, the castle passed to his son, Capt. Duncan MacRae (1890-1966) who, sadly, lacked his father's enthusiasm for the castle. The family returned to their other estates, Ballimore and Fornham Park (sold in 1949). Eilean Donan was hardly occupied until Duncan's son, the late Mr John MacRae (24th Constable, 1925-88), opened it to the public in 1955 and established a charitable trust (in 1983) to take care of maintenance. His widow succeeds him.

That so few of the hundreds of thousands of visitors who stop at Eilean Donan believe it to be anything other than a medieval castle is a tribute which would have pleased the men who built it. The castle is a celebration of the unexpected heights to which fortuitously combined - if hitherto unproven - talents can be forced once imagination is fired, so long as the wherewithal, in terms of time, money and simple devotion, is there to support it. For Watson the castle was the high point of an otherwise unspectacular career; his obituary in The Builder (June 4, 1948) adds only his restoration of Kirkwall Cathedral under "his principal works". But it was the irrepressible enthusiasm of John MacRae-Gilstrap, in many ways a Victorian figure, which was the driving force. He demonstrates yet again how energy and determination, catalysed by social ambition, can convert dormant fortunes into national monuments.

Photographs: 1, 3-6, by Paul Barker; 2 by RCAHMS. All images are available for purchase from the Country Life Picture Library. Please click your chosen image to be redirected.

RETURN TO THE SCOTTISH CASTLES HOMEPAGE

BALMORAL CASTLE: A HIGHLAND PARADISE BY MARY MIERS (FREE PDF DOWNLOAD)

BLAIR CASTLE: THE SEAT OF THE DUKES OF ATHOLL, PART 1 BY ARTHUR OSWALD

CRAIGIEVAR CASTLE: THE SEAT OF SIR JOHN FORBES, BART., NOW LORD SEMPILL BY PETER GRAHAM

CULZEAN CASTLE: THE SEAT OF THE MARQUESS OF AILSA, PART 1 BY ARTHUR T. BOLTON

GLAMIS CASTLE: THE SEAT OF THE EARL OF STRATHMORE, PART 1 BY OLIVER HILL

HOLYROODHOUSE: SCOTLAND'S ROYAL PALACE BY SIMON THURLEY (FREE PDF DOWNLOAD)

SCONE PALACE: THE SEAT OF THE EARL OF MANSFIELD AND MANSFIELD, PART 1 BY JOHN CORNFORTH

STIRLING CASTLE: RENAISSANCE OF A ROYAL PALACE BY JOHN GOODALL

Agnes has worked for Country Life in various guises — across print, digital and specialist editorial projects — before finally finding her spiritual home on the Features Desk. A graduate of Central St. Martins College of Art & Design she has worked on luxury titles including GQ and Wallpaper* and has written for Condé Nast Contract Publishing, Horse & Hound, Esquire and The Independent on Sunday. She is currently writing a book about dogs, due to be published by Rizzoli New York in September 2025.

-

Bye bye hamper, hello hot sauce: Fortnum & Mason return to their roots with a new collection of ingredients and cookware

Bye bye hamper, hello hot sauce: Fortnum & Mason return to their roots with a new collection of ingredients and cookwareWith products sourced from around the world, the department store's new ingredients and cookware collection is making something of a splash.

-

Sheep-herding dogs, The Archers and Sir David Attenborough: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 8, 2025

Sheep-herding dogs, The Archers and Sir David Attenborough: Country Life Quiz of the Day, May 8, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day features dogs, David (Attenborough) and radio drama.