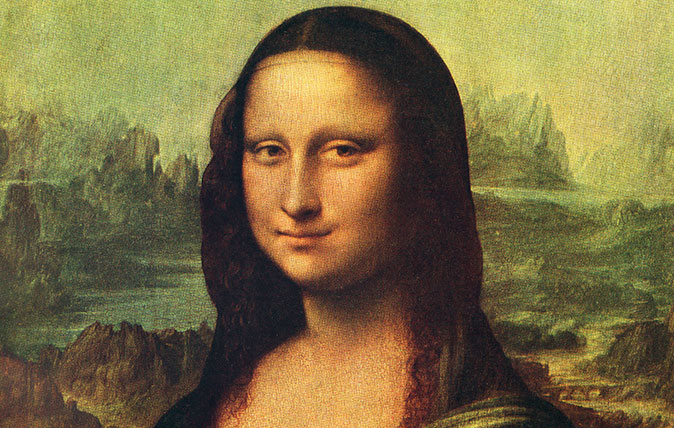

Jason Goodwin: The secret of Mona Lisa's smile? It's that smell coming from the kitchen

This week, our columnist reveals his secrets for creating a beautiful home-made cooking stock which will let you make all manner of wonderful dishes.

An imposing painting of a culinary deity, done in 1927 by Dietz Edzard, my stepmother’s father, used to hang in the kitchen at home.

It was a three-quarter-length portrait of La Mère Fillioux, a sturdy and celebrated Lyonnaise chef, eyes lowered, arms bare, her hair in a bun and leaning slightly forward as she prepared a chicken at the table. She wore a white apron and an expression of imperturbable satisfaction, like Mona Lisa with a useful job.

Mère was an honorific, given to certain women who ran restaurants in fin-de-siècle Lyon. Hers, which employed only women, had sawdust on the floor and the diners crammed onto tables surrounding the stove from which La Mère Fillioux produced the same menu every day for more than 30 years.

The menu consisted of artichoke hearts – or bottoms, as the French call them – with truffled foie gras, quenelles with shrimp butter and a famous truffle soup, using stock made with a dozen poulardes, those plump hens that the poultrymen of Bresse raise in four months or more.

La Mère Fillioux was supposed to have dispatched half a million of them over her lifetime, always using the same two knives, just as she never changed the stock in which the birds were simmered, year after year – except once, my stepmother recalls, when she started afresh in patriotic riposte to some long-forgotten affront.

All of that was implicit, too, in the Edzard portrait, perhaps the best painting he ever did.

The painting is long gone and Mère Fillioux died before the Second World War. She passed her expertise down to La Mère Brazier, who broke ranks and passed her knowledge on to Paul Bocuse, who died in Lyon earlier this year, in the house where he was born, but the stock – or the idea of it – lives on.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Into the pot go the green tops of leeks, carrots, a celery stick broken into bits, nothing from the cabbage family unless you want your kitchen to smell like a tenement in Novosibirsk, a few cloves, salt and pepper and water to cover.

Let it barely simmer or leave it in the bottom oven of the Aga. Add fennel, garlic, herbs and empty pea or bean pods in summer, for almost nothing need go to waste when you have a stock on the go. Parsley stalks are better flavoured than the leaves. Avoid boiling.

"It's secretly a bit like making compost, but higher up the food chain"

This is a meatless stock and, although I’m sure La Mère Fillioux would not disapprove, a stock is unquestionably enriched by the addition of bones and feet and muscle meat, including, of course, the remains of a roast chicken. I’ve taken to jointing butcher’s birds, using the breast and legs for other things and dropping the carcase raw, with its wings, into the stock pot.

I wouldn’t keep my stocks going for 30 years, or even three days, but a decent broth is almost free and is the foundation of any number of good dishes, from soups and risotto to stews and mash.

Tortellini taste better in brodo. For invalids, everything white is good, such as chicken soup or rice. And it’s only a skip to pot au feu, the traditional boiled dinner of France and elsewhere, including, I’m told, the fashionable pho of Vietnam, a beef or chicken stock with noodles, which may derive from the pot au feu introduced there by French colonists.

Thrifty, useful and easy to make, stock is also Buck-U-Uppo for the dogs. We use it to enliven their dreary kibble.

It’s secretly a bit like making compost, but higher up the food chain, with the ineffable satisfaction that comes from creating something good out of nothing. That, as La Mère Fillioux’s portrait suggests, could be the secret of the Mona Lisa smile.

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: 'Our headmaster was more Gilderoy Lockhart than Dr Arnold'

The graduation ceremony of Jason Goodwin's son reminds our columnist of the latin prayers which were so prolific in his

Jason Goodwin: 'On our watch, the natural glories of our island have been atrociously depleted'

Our columnist Jason Goodwin laments the staggering decline of British wildlife and the depletion of our island's natural glories.

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: How to turn a majestic but unlucky deer into a freezer-full of meals

Our columnist Jason Goodwin makes the most of a bit of A35 roadkill – with a little help from Christian Dior.