How to grow the bladdernut, a delightful shrub with the heavenly scent of vanilla custard

An email from a friend spurs Mark Griffiths to take a look at the curiously-named bladdernut, a vigorous and easily-grown shrub that needs just the right touch to really make help it come into its own.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

‘Any ideas?’ read the message accompanying a picture freshly-arrived in my inbox.

From time to time, friends email me photographs of unidentified plants that have taken their fancy and I do my best to oblige.

In this case, the task was easy. I was looking at a full-grown flowering specimen of Staphylea colchica, a deciduous shrub that will, given sunlight and pretty much any moist and reasonably fertile soil, soon achieve the height and presence of a small tree.

Lustrous light green and elegantly pinnate, its leaves resemble those of a well-mannered ash or walnut. With or soon after them, in spring and early summer, come the flowers in branching sprays of astonishing generosity. They recall orange blossom in shape and colour – typically sparkling white or ivory and sometimes, as in the cultivar Hessei, tinted rosy purple.

I’ve heard their perfume likened to orange blossom, too, but, encountered close-up on a warm day, S. colchica rewards me with vanilla-laced custard spiked with nutmeg. Either way, the flowers smell good enough to eat, which is exactly what happens to them in this species’ native Caucasus. Harvesting its buds, either from the wild or from bushes planted along farmland boundaries, is a rite of spring in parts of Georgia. They’re then washed, packed in salt and eaten year-round, usually with onions and olive oil.

Spared this fate, the flowers give rise to the large inflated pods that are characteristic of Staphylea and which account for this genus’s English name, bladdernut. These deck the branches well into the autumn, turning from pearly pale green to russet and parchment.

‘What’s not to like?’, you might reasonably ask. In recent years, however, S. colchica (which, I remember, was considered so very choice and smart in my youth) has fallen from favour in British gardens.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Its fault lies in its vigour. Suckering by nature, within a decade of planting, it can make a stockade of stems that’s 12ft tall and as much across. Out of flower, it’s just too much boisterous greenery and too little display to suit the prevailing fashion for tightly coordinated schemes and unceasing performance.

These days, if people are going to grow a bladdernut at all, they tend to go for S. holocarpa. This Chinese species is less suckering and more of a tree, albeit a slender and small one, rarely exceeding 20ft tall. Trefoil rather than pinnate, its leaves may colour beautifully in Indian summers, turning to amber and flame, and they’re reliably flushed with bronze and chocolate when they first emerge.

This latter feature makes for wonderful contrasts with the flowers, which, in the cultivars Innocence and Rosea, are respectively blush in bud and white on opening and persistently cherry-blossom pink. In fruit, it can also be strikingly decorative, its bladders often ending up dusky crimson.

Given all of which, it is little wonder that Staphylea holocarpa has supplanted its Caucasian cousin in horticultural affections or that, on receiving my friend’s email, I felt I was looking at a photograph that might have been taken in a more liberal and less self-conscious garden 30 years ago.

However, each of these bladdernuts has its place and both, happily, are available from some of our finer tree and shrub specialists, most notably Bluebell Nursery in Leicestershire (www.bluebellnursery.com).

Even when young, S. holocarpa Rosea is an exquisite centrepiece or backdrop for a small spring garden full of bulbs, unfurling fern fronds and precocious herbaceous perennials. On a larger scale, it and its fellow cultivar Innocence are sublimely delicate companions for magnolias, camellias and ornamental cherries in arboreta and woodland plantings.

As for Staphylea colchica, try it in an informal and marginal area where it can surprise and delight in season and, at other times, do its thing without boring or imposing.

That said, rather than leaving it to its own devices, you may wish to train it a little. Once established, its many stems collectively form a loosely pyramidal crown with gracefully arching boughs. This looks all the better and all the more legible in the landscape, if one prunes out any small branches that appear lower down and excises at ground level all but a few of the strongest new shoots.

Although it may have lost its former home in the garden – the old-fashioned shrubbery – a new and better one awaits S. colchica in orchards and meadows. Picture it amid the lush grass, perhaps in company with those other great spring-flowering shrubs that so richly deserve to be revived and redeployed, the lilacs.

Mark Griffiths it the editor of the New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening.

Credit: Alamy

The daftest plant name in English, and how it belongs to a wonderful flower just starting to show its potential

There are a lot of silly names for flowers our there – and Charles Quest-Ritson has a chilling warning for those

Dahlias, the 'miracles of complexity' that we've learned to love and cherish

Charles Quest-Ritson talks about dahlias, once so unloved, and how they enjoying a surge of popularity.

Credit: Alamy

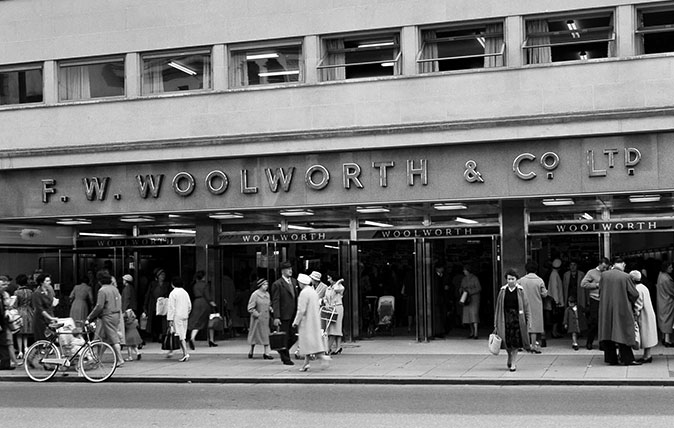

The day that Woolworths accidentally sold me an endangered species

Charles Quest-Ritson reminisces about the day his bargain purchase of a cyclamen in Woolworths proved to be something rather special.

Life, death and daphnes – and the variety that goes in and out of extinction peril

Charles Quest-Ritson muses on daphnes, the lovely winter flowers which seemingly ought to be a lot hardier than they are.

The worst garden pests of all? The ones you invite in with open arms

A couple of weeks ago, Alan Titchmarsh wrote a lovely piece for Country Life about how to get children and