How to choose the perfect rose this bare root season

Looks can be deceiving: bare root roses are hardier and more sustainable than potted ones, says Tabi Jackson Gee, who moved to a cottage in Wiltshire and went about finding the perfect plant. You just need patience.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We moved to our Wiltshire cottage two years ago this November and, at the time, the front garden was overgrown with shrubs. However, among them I counted — with glee — 15 mature roses.

Come spring, my joy was dashed because each rose, now flowering, was a different colour. And they didn’t have much scent. It wasn’t the romantic and charming garden I had envisioned. So, I started on a brutal editing process, trying to find some peace and elegance amid the overgrown cottage garden chaos.

Only three of the roses survived the cull: The Lark Ascending, Thomas à Becket and Lichfield Angel (incidentally, all David Austin breeds). All have beautiful, showy flowers, are scented and bloom repeatedly, more than earning their keep. However, I also wanted to add my own into the mix and so began the terribly difficult task of choosing a rose.

'The unassuming bare root rose produces just the same vibrant, beautiful flowers as any potted rose with many added benefits,' say the team at David Austin who launched a campaign highlighting their oft-overlooked beauty.

I waited until the following autumn and the return of bare root season; the period between November and March when nurseries sell plants — mainly shrubs and trees — that have been grown in open ground rather than in containers. It’s best practice to plant dormant trees, shrubs and roses as bare root specimens because the manner in which they’ve been grown makes them more resilient. Container-grown plants are the pampered younger siblings of this world, protected from harsh weather and molycoddled in compost.

Open ground-grown plants also have much more room in which to develop their roots. In fact, gardeners are increasingly seeking out bare root perennials, too. Aside from the fact that they’re longer lasting, they’re also lighter and arrive with a lot less packaging (say goodbye to vast amounts of plastic that you have to guiltfully dispose of into landfill).

'As well as climbers, roses come as ramblers, shrubs, trees and as sprawling ground cover.'

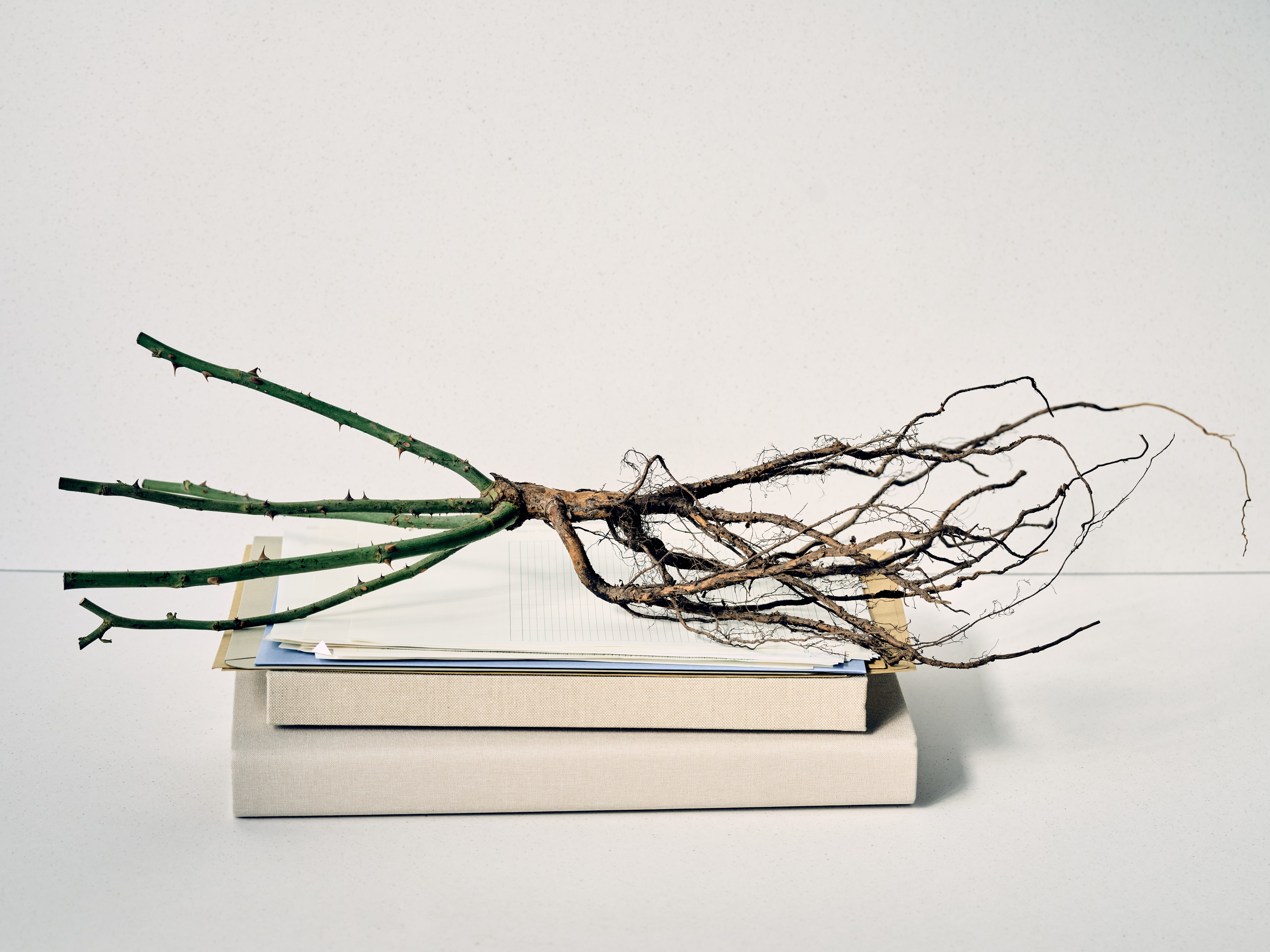

The roots are the first thing you will notice when you buy a bare-root rose because they are not delivered to you in soil or in a pot, but, well, bare… a lightweight plant that is half brown root system and half green canes. A bud union — or graft joint — will be visible. This is the point at which the rose has been grafted onto the root stock which makes it adaptable to different conditions and less prone to disease.

When you’re holding this unassuming and knotty brown thing in your hands, it’s hard to imagine that in six months it could be double the size and covered in clusters of flowers. Give the plant a once over before you do anything with it because healthy roots are imperative to a success.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

I went into the process of choosing my roses with a checklist of requirements. I wanted something that would flower more than once a year, and something that would survive full sun exposure and blossom in our lovely, loamy soil (although roses are happy in most conditions except deep shade or anywhere too damp). I walked through the front green space multiple times a day, in different lights, and worked out what I could see from my washing up spot in the kitchen. I also desperately wanted a climber because much to my disappointment (again) the cherry tree I’d stared at for months through winter, patiently waiting for it to blossom, was, in fact, dead. It would, however, make the perfect climbing rose support.

Bare root roses arrive with a lot less packaging to contend with.

As well as climbers, roses come as ramblers, shrubs, trees and as sprawling ground cover. They can even be planted as hedges — Rosa canina is good for this. The majority of garden roses in production today are hybrid varieties, bred for their scent, colour, growth-rate and flower shape. According to Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, roses are thought to be more than 30 million years old and there are a staggering 30,000 varieties and 300 accepted species. Only about 20 of the latter are the ancestors of all modern cultivated roses. (‘Species’ refers to the plants that occur naturally in the wild; varieties are the descendants of those plants that have been bred and cultivated to have certain characteristics.)

As a garden designer, I am lucky to visit clients with lengthy rose arbours, well established climbers sneaking up the side of houses, roses burgeoning in herbaceous borders and wild roses in blousy meadow settings. Roses can and should be grown for cut flowers — at his home, in Somerset, landscape designer Dan Pearson has Munstead Wood, Gertrude Jekyll, Mortimer Sackler, Jubilee Celebration and Sceptre’d Isle in his cutting garden.

The winning rose, Mme. Alfred Carrière.

In the end, I chose a strong and bushy climber called Mme. Alfred Carrière. The Madame has dark and glossy green foliage, and loose, creamy petals with just a whisper of pink. It smells sweet and fruity, flowering first in June or July and repeating late into the season. She came from David Austin, which is where I regularly buy roses from for clients. Had I been on the hunt for an older breed of rose, I would’ve looked to family-run and Norfolk-based Trevor White — fellow Country Life-contributer Isabel Bannerman is a customer. Other good companies include Ashridge Nurseries and Peter Beale. When shopping around, the most important thing to do is to look for plants that have been grown in the UK and in peat-free soil.

My rose arrived in November 2024 and I kept it in a cool and dark room until I could plant it. When that time came, I first soaked the roots in a bucket of water for two hours, an essential step that rehydrates everything following an extended period of time above ground and in transit. Next, I dug a large hole, a few inches from the base of my cherry tree in soil that wasn’t too soggy (if it’s recently rained, wait) and loosened everything at the bottom, before adding in compost and then the rose (the bud union should be about two inches below the surface). Finally, I watered it, and then waited, and then watered it again all summer long, and waited, gently coaxing it towards the tree that I hope it will one day envelop.

Next time around, I will be more organised and feed it homemade comfrey tea, though any organic rose food will do. I’m hopeful that, in 2026, Madame will flower for the first time, but roses can take a moment to get going, so I recommend patience.

Tabi Jackson Gee is a garden designer and writer based in Wiltshire. She is also the founder of Them Outdoors, an online gallery for original, design-led garden furniture, planters and sculpture made by British artists and craftspeople. Tabi trained at London College of Garden Design at Kew, and her work has been nominated and won awards with the Society of Garden Designers.