'Comfortable, cosseting and far from the madding crowd': The recently refurbished Cornish cottage that proves Victorian decor is making a comeback

Plum Cottage in Padstow, Cornwall, has been brought to life by Jess Alken and her husband, Ash — and is the latest addition to their holiday cottages on the north Cornish coast.

Black-and-white images of Victorian domestic interiors tend to reveal an unhinged eclectism that would send a minimalist running for the smelling salts; folding screens, aspidistras, antimacassars, ostrich feathers, dried flowers, taxidermy — even the family dog was in danger of being festooned with a tasselled pelmet if it was foolish enough to stand still for long.

This aspect of Victorian interior design is the subject of Domestic Gods, in which the author, Deborah Cohen, examines why some Victorians had such an insatiable appetite for stuff. It kicked off early in the century, but grew exponentially later on when ‘rising incomes combined with the bounty of industrial manufacture carried this tide of consumption to new heights’.

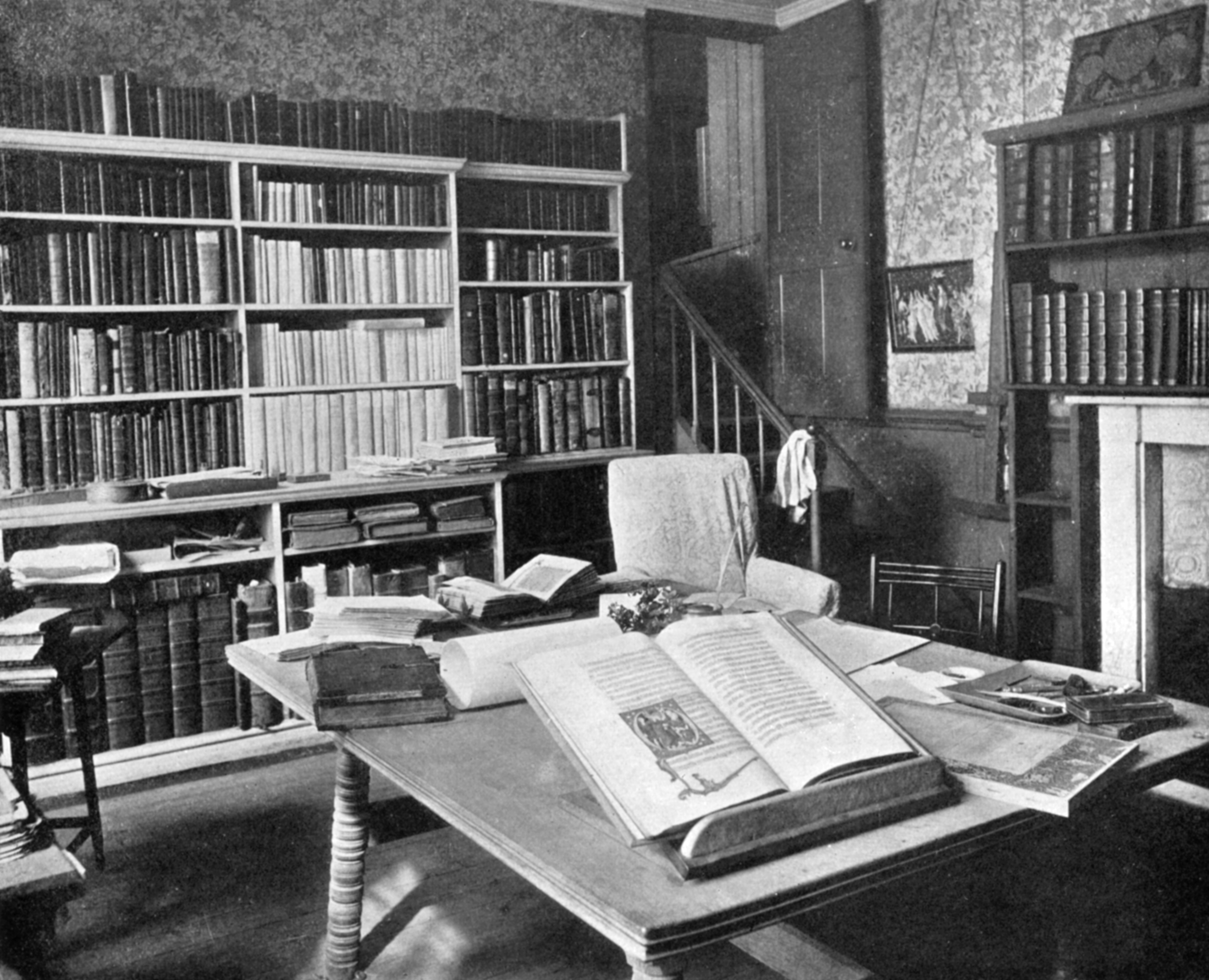

William Morris's study at Kelmscott Manor, photographed in 1901.

Where the Great Exhibition helped create the desire, the emergence of new temples to consumerism, Selfridges, Liberty and Derry & Toms sated it. The focus of her book, however, is on a certain type of Victorian home, namely those of the urban rich in London and the other burgeoning cities, the fortunes of which grew exponentially during the Industrial Revolution. Of course, there were plenty of Victorians who were more considered in their approach; contemporary depictions of Kelmscott Manor when William Morris and his family lived there depict rooms arranged with enormous discipline and Robert Tait’s painting of Thomas Carlyle’s house in Chelsea shows a more modish interior decorated with similar restraint.

Robert Tait’s painting of Thomas Carlyle’s house in Chelsea.

Beatrix Potter’s home, Hill Top in Cumbria, offers an insight into the decoration of humbler houses of the time. Although Sir John Betjeman and Gavin Stamp succeeded in changing perceptions of Victorian architecture in the closing decades of the 20th century, late-19th-century interiors have rarely received the adulation enjoyed by those of the Georgian period.

There have been flickers of interest; Uncle Monty’s London drawing room in Bruce Robinson’s filmWith-nail and I revived interest in the sybaritic pleasures of Victorian upholstery (and Ziegler carpets) and the appeal of Morris & Co and Liberty fabrics have never really gone away. In the 1970s, Laura Ashley achieved considerable success summoning up a stylistic amalgam of Victorian and Edwardian country style, but it was soon eclipsed by the pared-back aesthetic of Terence Conran’s Habitat.

There are signs, however, that a new generation of designers is discovering that the simpler style of rural Victorian interiors offers the perfect way to bring to life smaller houses and cottages of the period (a decade ago, the knee-jerk reaction was to paint them white from top to toe).

For their 19th-century owners, these houses were sanctuaries from the demands of hard work and the weather, in contrast to the maximalist homes of the affluent townspeople, for whom, as Prof Cohen writes, ‘possessions became a way of defining oneself’. In more modest homes, furnishings were valued for comfort, pleasing looks and utility, in line with William Morris’s maxim that one should avoid anything in a house that is neither beautiful nor useful.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

An artfully conceived example is Plum Cottage in Padstow, Cornwall, which has been brought to life by Jess Alken and her husband, Ash, the latest addition to their growing collection of highly atmospheric holiday cottages on the north Cornish coast.

The master bedroom at Plum Cottage, which has a touch of the 'With-nail and I' look.

Antiques, artwork and layered fabrics are key to the look of Plum Cottage’s sitting room.

Its interiors were designed in partnership with Tom and Katie Cox, the siblings behind HÁM Interiors. The mixture of antiques, artwork and new pieces inspired by the past, combined with a layered mix of fabric and wallpaper, creates a look that is a stylish celebration of Victorian domesticity. Alken was brought up at nearby Harlyn House (now The Pig hotel), and this project offered an opportunity to restore a house of more manageable proportions. The result is all you’d want a cottage to be: comfortable, cosseting and far from the madding crowd.

-

A spectacular green oasis that offers a slice of country life in the very heart of one of the busiest places in London

A spectacular green oasis that offers a slice of country life in the very heart of one of the busiest places in LondonAmong the roads, rail and conference centres of Earls Court, there's a charming terrace where you can find homes that offer wonderful surprises — and they don't get much more wonderful than this one.

-

What, we hear you cry, is a baby hedgehog called? Find out in the Country Life Quiz of the Day, September 25, 2025

What, we hear you cry, is a baby hedgehog called? Find out in the Country Life Quiz of the Day, September 25, 2025Spoiler alert: the answer is unbearably cute.

-

Interiors of excellence: all the events and inspiration you can't miss

Interiors of excellence: all the events and inspiration you can't missOver the next month, events at the Design Centre, Chelsea Harbour and beyond will offer plenty of inspiration for design lovers

-

The Mitford family once called this handsome Cotswolds house a home — and it inspired Nancy's greatest novel

The Mitford family once called this handsome Cotswolds house a home — and it inspired Nancy's greatest novelMary Miers is enchanted by the one-time home of the Mitfords — whose spirit lingers in the walls.

-

How shoe designer Penelope Chilvers transformed two adjacent rooms into a spacious kitchen

How shoe designer Penelope Chilvers transformed two adjacent rooms into a spacious kitchenArabella Youens meets shoe designer Penelope Chilvers who collaborated with Neptune to transform her kitchen, dining space and bootroom.

-

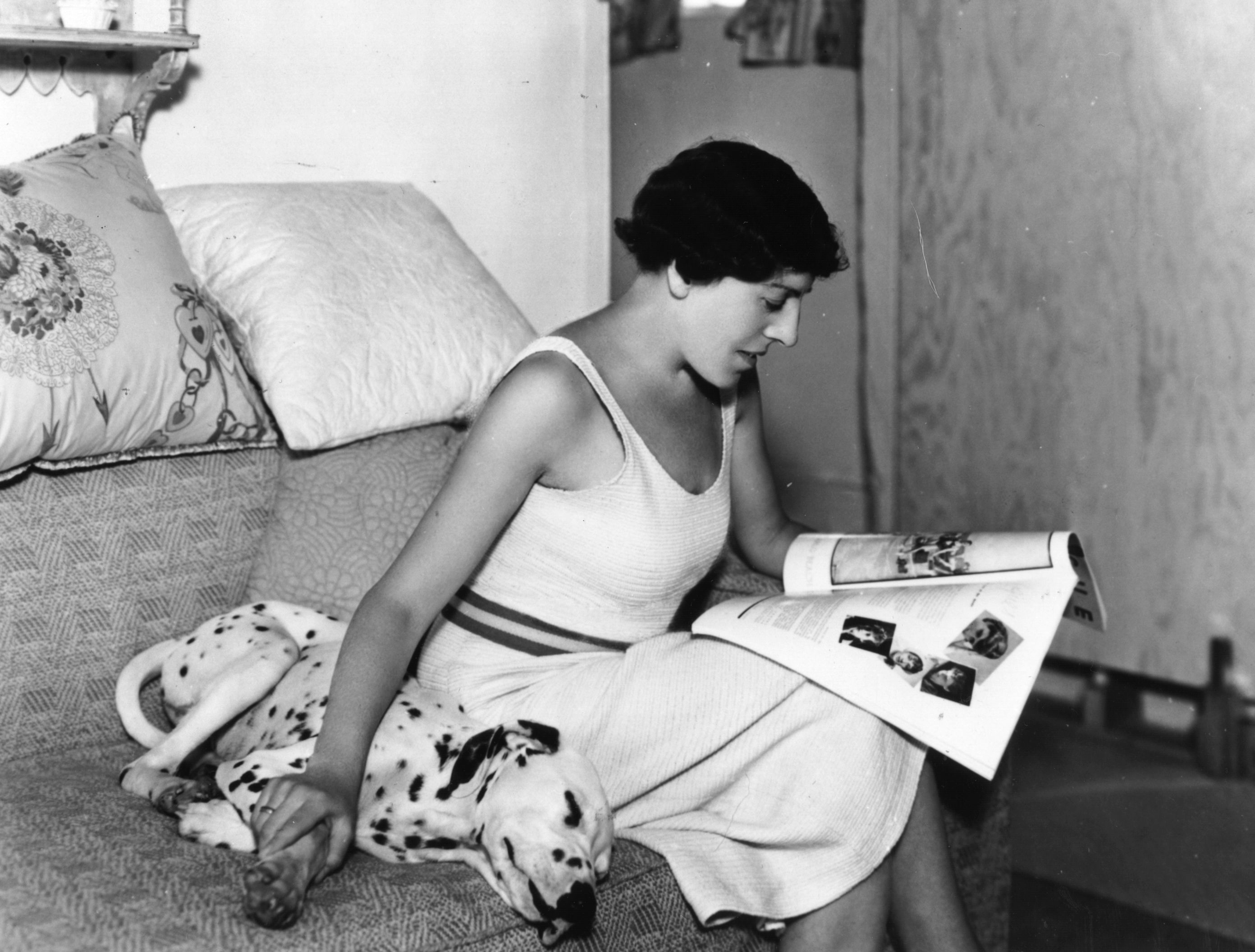

Country Life's never-before-published photographs of ‘101 Dalmatians’ author Dodie Smith's London flat

Country Life's never-before-published photographs of ‘101 Dalmatians’ author Dodie Smith's London flatEvery Monday, Melanie Bryan delves into the hidden depths of Country Life's extraordinary archive to bring you a long-forgotten story, photograph or advert.

-

Giles Kime: 'Why contemporary art should become a feature of everyday life'

Giles Kime: 'Why contemporary art should become a feature of everyday life'The belief that contemporary art looks best when displayed against a white, minimalist backdrop is dangerous — it can also make it look irrelevant, our Interiors Editor writes.

-

The designer's room: This kitchen in a Queen Anne-style home is proof that pretty and practical can go hand in hand

The designer's room: This kitchen in a Queen Anne-style home is proof that pretty and practical can go hand in handHiding the conveniences of modern-day living lends a timeless feel to the kitchen of this 18th-century house.

-

Giles Kime: 'Darkness in an interior is equally as beguiling as large amounts of natural light'

Giles Kime: 'Darkness in an interior is equally as beguiling as large amounts of natural light'Why subtle lighting is about more than a dimmer switch.

-

'Tones of natural wood and warm olive': Isabella Worsley transforms a coastal Sussex kitchen

'Tones of natural wood and warm olive': Isabella Worsley transforms a coastal Sussex kitchenFor this kitchen on the Sussex coast, Isabella Worsley dispensed with a classic seaside palette and turned to rich colours and natural textures