How the French impressionists came to fall in love with London

French artists flocked to London in the late 19th century – and while they weren't exactly willing exiles, most to love their new surroundings as a new Tate exhibition shows. Caroline Bulger explains.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

‘No Frenchman goes to England for pleasure, or resides there by choice,’ asserted the French novelist and critic Hector Malot in 1862.

Within a decade, he was proven spectacularly wrong. Malot’s artistic compatriots were flocking to the city. Not that they came for pleasure – they were seeking refuge from the horrors of the Franco-Prussian War – but they were there by choice.

The grim reality behind this exodus is illustrated in the opening section of the new exhibition at the Tate Britain with a series of works depicting scenes of battle, executions and iconic buildings reduced to rubble during the siege of Paris.

Some French artists fled to the provinces, but others – including Charles-François Daubigny, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, James Tissot and Alfred Sisley – crossed the English Channel and established themselves in London.

There, they found a French community in Soho, a congenial watering hole in the French-owned Café Royal in Regent Street, museums with fascinating collections, potential buyers for their works and a welcome both from compatriots already settled in the city and from some English artists.

However, with notable exceptions, they found little to admire in contemporary British art. ‘How awful modern English painting is! They certainly have need of our influence,’ remarked Daubigny.

The refugees were often homesick and miserable and the climate seemed unutterably depressing. ‘Here I am in London, experiencing exceptional fog,’ wrote the artist François Bonvin. ‘Hell! It is not fun! I had been warned, but not sufficiently!’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Cramped lodgings made painting out of doors especially appealing, smog notwithstanding, especially when there was the prospect of working alongside fellow exiles.

There was also the stimulus of fresh new subjects. The Palace of Westminster, recently completed, was a massive neo-Gothic anthem to British might and Empire, and unlike anything in Paris. A superb view of it could be had from the Thames Embankment, which had also just been finished and was a major attraction in its own right.

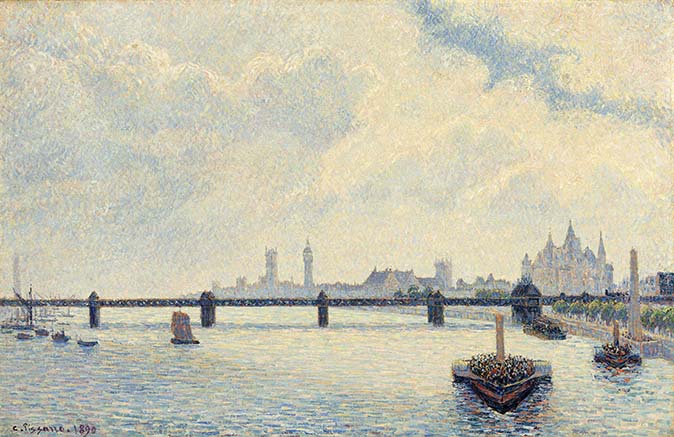

Any artist setting up an easel along the Thames could also survey the comings and goings downriver – barges filled with cargo, warehouses, wharves and cranes, all witnesses to the busy commercial life of the city. It was perfect for the painter who wanted to capture the complexities of modern life.

Tissot, who had seen appalling suffering during his time as a soldier in Paris, was drawn to the more social aspects of life on the water. He trained his eye on the English at leisure in paintings such as The Ball on Shipboard, which depicts an afternoon dance at Cowes Regatta and is the type of festive modern scene that Renoir and Manet favoured back in France.

For those in search of Nature, there were London’s parks, which held a particular appeal for Monet. These green spaces, offering a welcome expanse of countryside in the heart of the city, were places where people from different social classes were free to mingle and wander over the grass, rather than sticking to formal paths as they did in Parisian parks.

The suburbs also had a semi-rural charm. Pissarro settled in Upper Norwood, where his mother and brother were living, and painted its leafy avenues in springtime, streets under snow, nearby Crystal Palace and a train steaming out of Lordship Lane station, linking suburb and city.

Alfred Sisley, sent to London by his dealer in 1873, found subjects in the suburbs as well, including bathers at Molesey Weir near Hampton Court.

Most of the artists who would become known as Impressionists went back to France after the end of the war and the brutal suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871, although Tissot, whose art was attracting wealthy English patrons, stayed on for a further decade.

But their period of exile had forged closer links with London and, having overcome any initial misgivings about the city, many made further visits. When he returned in 1893, Pissarro gravitated towards Kew, attracted by such quintessentially British vistas as the rhododendron dell in the Botanic Gardens and the cricket on Kew Green.

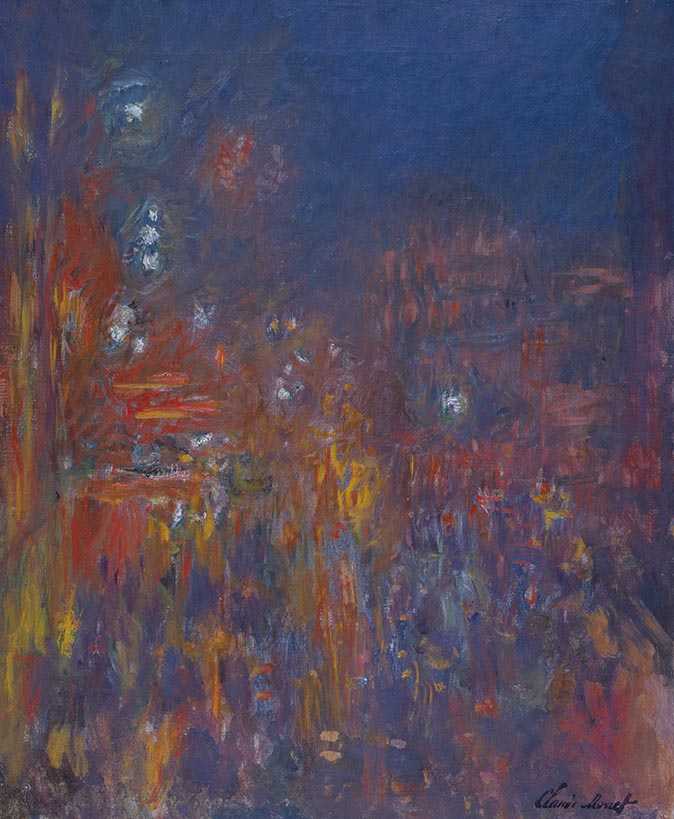

By the time Monet came back for his final stay in 1903, he was even singing the praises of the city’s murky atmosphere: ‘It’s the fog that gives London its marvellous breadth. Its regular massive blocks become grandiose in this mysterious cloak.’

The misty river proved irresistible to him, as it had been years earlier to another expatriate, the American James Whistler. Between 1899 and 1901, Monet started some 100 canvases of Charing Cross Bridge, Waterloo Bridge and the Houses of Parliament.

The exhibition will reunite six of the paintings from his magnificent ‘Houses of Parliament’ series, all of them painted on canvases of a similar size and from the same viewpoint, showing the spiky silhouette of the Palace of Westminster looming through the haze at sunset, but in different light conditions.

Monet’s paintings went on show in Paris in 1904, the year of the Entente Cordiale between England and France, and one young visitor, the artist André Derain, was so inspired by them that he made his own trip across the Channel two years later, deliberately taking on the subjects that Monet had tackled.

How different his approach was, however. In place of Monet’s feathery brushstrokes and vaporous suggestion, Derain’s forms were bold, his colours clear, brilliant and unnaturalistic: an audacious modern vision for a new century.

‘Impressionists in London: French Artists in Exile’ (1870–1904) is at Tate Britain, Millbank, London SW1, from November 2 to May 7, 2018 (020 7887 8888; www.tate.org.uk)

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.