Power, prestige and passion: Where to see more than 100 of the world’s best dynastic jewels

Many of the world’s most astonishing jewels are on display together in Paris — and they once belonged to Europe’s most powerful families.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The recent Louvre theft aside, what's astonishing is that many of the world's royal jewels have survived the vagaries of history. At an exhibition at Paris's Hôtel de la Marine, more than 140 of the best are on display.

Three years in the making, ‘Dynastic Jewels’ is the third and final collaboration between the Al Thani Collection and the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A), and looks at the power, prestige and passion of dynastic jewels. It combines stunning pieces from their two collections with others from public and private collections, and archives from high jewellery houses. ‘It's a once-in-a-generation chance to see so many of these incredibly important pieces of historical jewellery displayed together,’ says exhibition curator Emma Edwards.

The location of the show is noteworthy, as it was once the royal furniture repository, where Louis XVI exhibited the crown jewels to the public one day a month. This was also the site of another famous robbery, in 1792, during the chaos of the French Revolution — though most of those jewels were recovered.

The exhibition opens with celebrated stones from history, including the 57.31-carat Star of Golconda, from India's legendary diamond mines. While south Asia was rich in diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds, and attributed divine or talismanic properties to them, pre-Renaissance Europeans had limited access to gemstones, particularly diamonds. That changed in 1498, when the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama opened a maritime route to India.

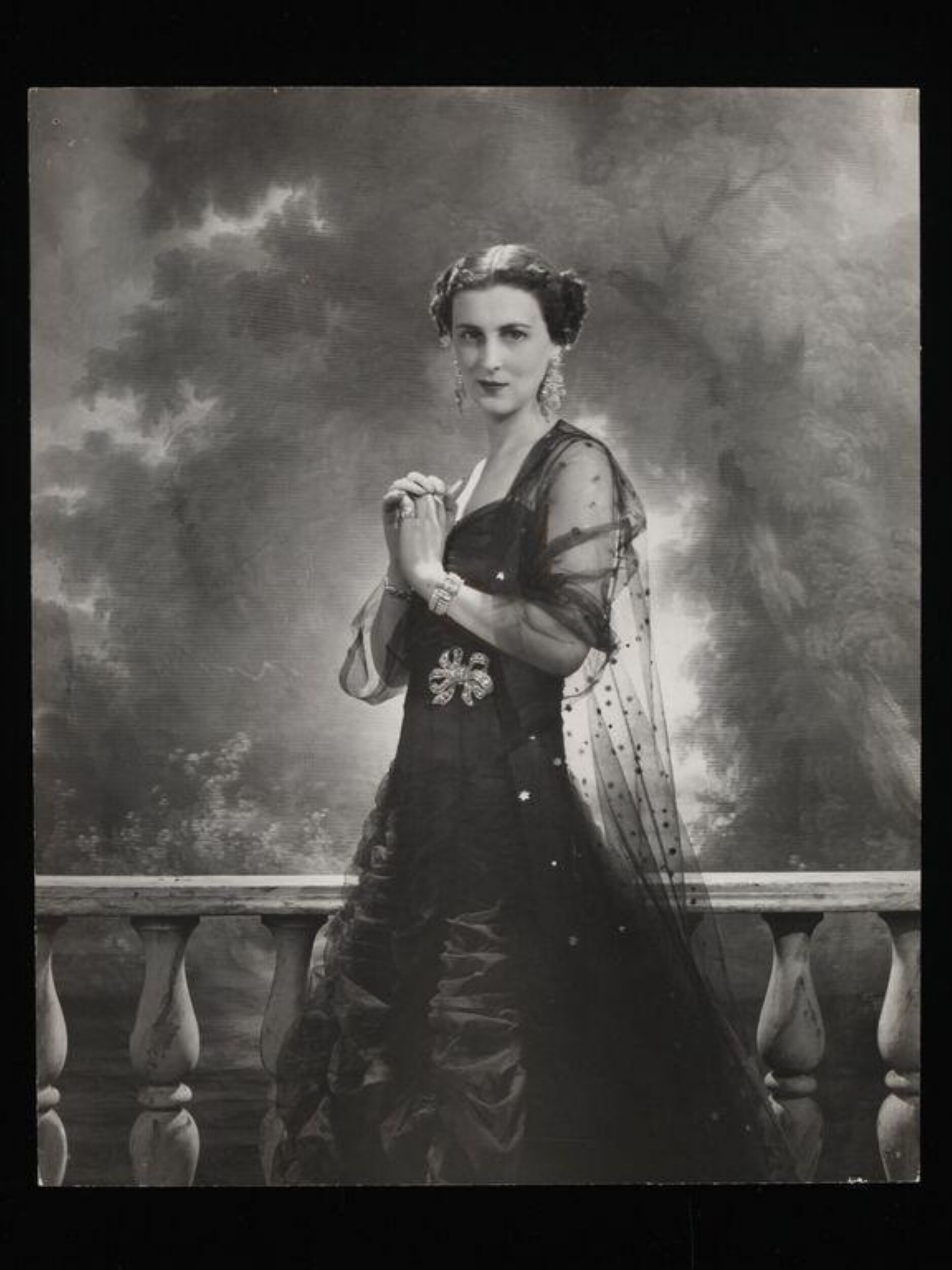

Princess Marina of Greece, Duchess of Kent, in the Romanov diamond bow brooch and Girandole earrings.

Trade in precious stones grew quickly after that, transforming European court fashion, where the custom was to sew them directly onto clothing. Louis XIV thus covered himself from head to toe with Indian diamonds, reinforcing his position as the divinely appointed Sun King.

In Russia, Catherine the Great used jewellery to help secure her authority following the coup d'état that gave her the throne. She immediately commissioned an imperial crown studded with diamonds, and created a room in the Winter Palace to display the royal collection. ‘She really knew how to manipulate the use of diamonds and jewellery so that she shone,’ says Emma. ‘We have some dress ornaments that were used to cover her splendid court attire so that she blazed around her courtiers and everyone knew who she was.’

The 57-carat Star of Golconda diamond.

Napoleon Bonaparte also used jewellery to legitimise his authority as emperor. One of the stars of this show is the sword from his coronation. ‘The sword was designed to house the Regent diamond [now replaced], a statement of the continuity that he wanted to instill in his reign — that he was the successor to the royal kings of France,’ says Emma. His coronation crown was a copy of Charlemagne's, while Josephine wore a diamond tiara that referenced the laurel wreaths of the Roman Empire.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Ancient Rome influenced women's clothing styles under the Bonapartes, as fabrics grew lighter and more delicate, representing innocence and purity. As a result, jewels moved to the body, such as the pearl necklace on display that Josephine is believed to have handed down to her stepdaughter, Princess Augusta Amélie de Bavière.

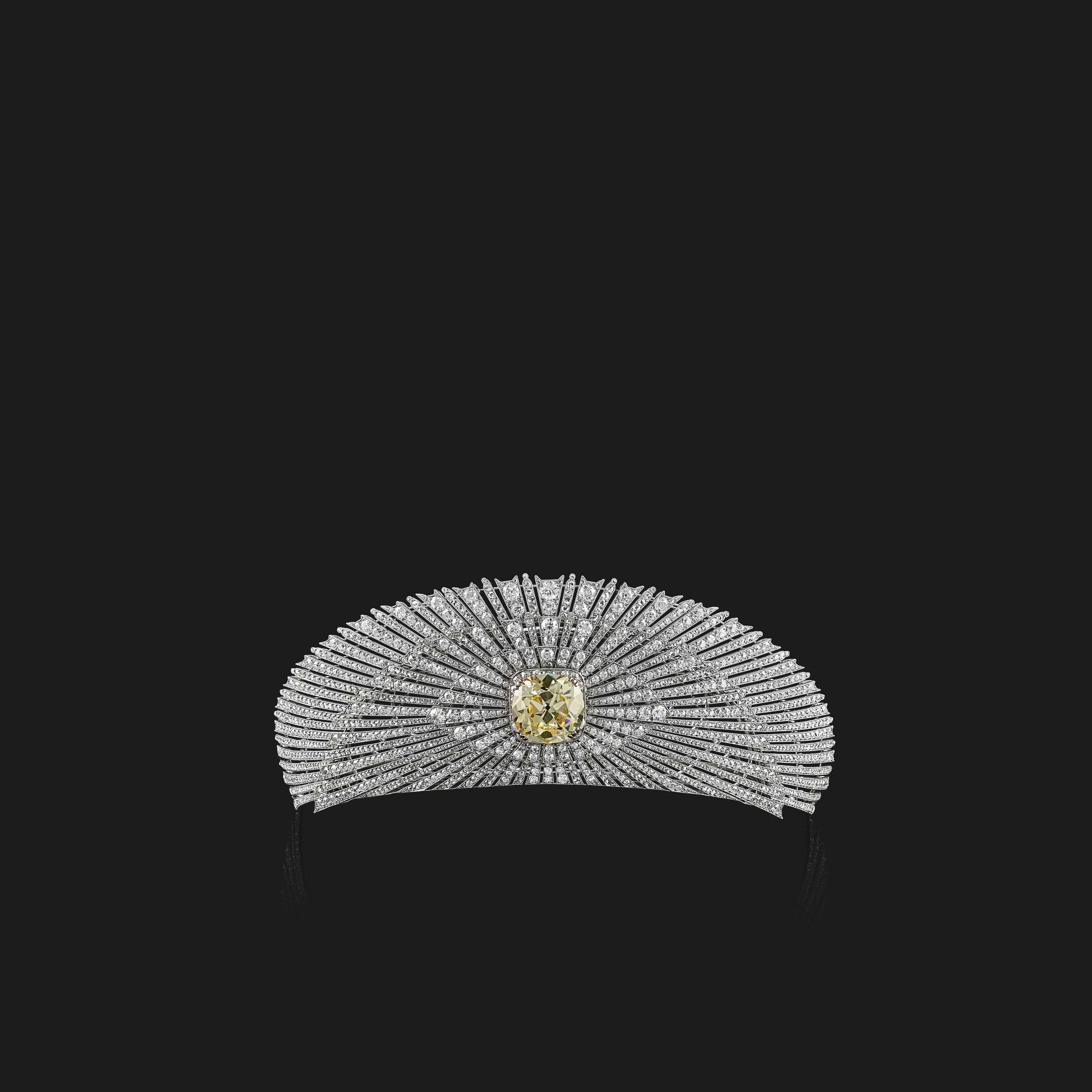

Cartier's Sun tiara features a 32-carat, fancy yellow diamond at its centre.

Pearls were extremely valuable, and could be more expensive than diamonds, until the invention of cultured pearls in the early 1900s. Empress Eugénie, consort to Napoléon III, owned a remarkable pearl-and-diamond tiara that was meant to be in this show, but disappeared in the Louvre theft. But Eugénie had plenty more in her jewellery box, and Mellerio, France's oldest jewellery house, has loaned the exhibition the magnificent peacock feather brooch that it made for her in 1868 with diamonds, emeralds, rubies and sapphires.

Another highlight is the simple sapphire and diamond coronet that Prince Albert designed for Queen Victoria in 1840, their wedding year. She wore it in her first official portrait, and copies of the painting were given as gifts around the Empire. The beloved piece is shown next to her emerald-and-diamond tiara, also designed by her regent and realised by Joseph Kitching. As both were passed down to other family members, Emma says, ‘you can speculate that they might have been worn together at fabulous house parties, but they haven't been seen together for a very long time’.

From the late 1800s to the early 20th century, tiaras were the de rigueur headpiece for high society and royal events, and a room at the Hôtel de la Marine is devoted to 11 of them. One, a large, crown-like confection with a matching stomacher was crafted by Garrard for the Duchess of Portland. ‘She was this very tall, elegant Edwardian lady,’ Emma says. ‘The stomacher was made out of jewels that the family owned, and the tiara was made to go with it. The two of them together, within a ballroom setting, would have really made a statement about who you were and your social standing.’

There are the remnants of a tiara given by the future George IV to the twice-widowed (and Catholic!) Maria Fitzherbert, whom he wed in secret. The alliance was invalidated and George agreed to marry Caroline de Brunswick in exchange for his father paying off his colossal debts.

The Manchester tiara also starred in the V&A's 'Cartier' exhibition.

And then there's the Manchester tiara, made by Cartier in 1903 for the Duchess of Manchester, one of the dollar princesses, or nouveau riche who came from the USA to bolster up the dwindling fortunes of the British aristocracy.

Indeed, the centre of power was now moving from Europe to the New World. Monarchies from France to Austria-Hungary to Russia collapsed, and the new regimes wanted to keep jewels out of the hands of any pretenders to the throne. When France's Second Empire fell, Eugénie wrapped up some of her jewels in newspaper and took them to England, where she gradually sold them to support her life in exile. Back in France, the republican government auctioned off 77,000 Crown jewels in 1887, which proved to be a financial disaster. The biggest buyer was the New York jeweller Tiffany & Co.

This was the Gilded Age, and royal jewels were now worn by the new powerbrokers with names like Vanderbilt and Astor and Rockefeller. One exquisite piece in this exhibition is a corsage brooch created by Mellerio dits Meller in 1864 for Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III. Emma calls it ‘a study in naturalism’, a fully bloomed rose set with 2,309 diamonds. The princess, known for her beauty, wore it when hosting salons for Paris's literary and artistic elite. After her death in 1904, it was sold to Mrs Cornelius Vanderbilt III, who showed it off at high-society parties in New York.

In the 20th century, Maharajahs brought trunks of jewels — such as this 213-carat Mughal emerald — to France to have them set in modern styles.

The 20th century also saw the return of India's influence on jewellery, as maharajahs' fortunes swelled during the British Raj. They brought trunks filled with jewels to Paris, to have them reset in a modern style by jewellers of the Place Vendôme — Mauboussin, Boucheron, Van Cleef & Arpels, Chaumet (whose founder, Marie-Etienne Nitot, had been Napoleon I's jeweller) and especially Cartier.

Jacques Cartier travelled frequently to India, where his biggest clients were not women, but men. He made a necklace with multiple chains of diamonds for the Maharajah of Patiala, and a turban ornament featuring a rare brown tiger eye diamond for Maharajah Ranjitsinhji de Nawanagar. In turn, India's exoticism influenced Western taste, as the heiress Daisy Fellowes commissioned Cartier to make a ‘Hindu Necklace’ in its colourful Tutti Frutti style.

In 1933, a woman, Jeanne Toussaint, became director of high jewellery at Cartier. Her nickname was La Panthère, and she leaned into the house's panther motif, creating sculptural versions for Wallis Simpson, such as a diamond and sapphire panther seated proudly on a large sapphire cabochon. The Duchess of Windsor wore the brooch on her shoulder — a power statement if there ever was one.

Dynastic Jewels is open until April 6, 2026, at the Hôtel de la Marine. Click here for more information.

Amy lives in Paris and has worked for years as a journalist and editor in chief covering a range of subjects, including culture and the arts for The New York Times and National Public Radio, business and technology for Fortune and SmartPlanet, architecture and design for Wallpaper*, food and fashion for the Associated Press, and humanitarian issues for the International Committee of the Red Cross. Sometimes she also writes dialogue for The Smurfs.