Dragonflies, flowers, dogs and lobsters: The 17th century nature brought back to life by the paintings of Alexander Marshal

Alexander Marshal — this country’s first major botanical painter — deserves to be better known, writes Tiffany Daneff, after seeing his luminous originals in the Royal Collection.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

‘Hee might have 500.lb. for his Picturary of flowers if hee would take it,’ wrote Samuel Hartlib in 1654 of his friend Alexander Marshal, the keen gardener and painter who had devoted his life to painting the flowers in his own and his friends’ gardens. These brilliant watercolours — of 600 different plants, native and exotic, as well as insects, birds and animals (including some remarkably awkward greyhounds) — represent the most important surviving work by Marshal, our first botanical artist. Shockingly, perhaps, it is also the only extant British Florilegium of the 17th century.

Flower books were popular on the Continent, where they were a happy offshoot of the passion for collecting — being the only way one’s treasures could be recorded. Indeed, the use of the word ‘Florilegium’ to mean a book of flower paintings was coined by the Flemish artist Adriaen Collaert (1560–1618) in 1590. Marshal, who was fluent in French, possibly grew up in France, where many flower painters worked. He might well, therefore, have seen the works of Daniel Rabel (1578–1637) and been inspired by the way the Frenchman decorated his flowers with insects and butterflies. Rabel’s countryman Nicolas Robert (1614–85), who produced the Vélins du Roi — botanical paintings on vellum — for Louis XIV, was similarly prominent, but there was no major British player until Marshal.

These double red and large blush peonies were painted in about 1680.

Despite the high offer, it is fortuitous, perhaps, that Marshal didn’t sell his Picturary as, after his death, the paintings eventually passed to his wife’s nephew and, by a circuitous route, were presented to George IV. Today, they are safely stored in the Print Room at Windsor Castle, Berkshire, where Country Life was privileged to see them.

There are more than one million items in the Royal Collection, ranging from Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci drawings to the grand piano from RY Britannia. It was Prince Albert who instigated the cataloguing of the ever-expanding collection of works on paper, being determined to bring some order to the extensive historic collections spread throughout the royal palaces. At his request, the designer, architect and sculptor John Thomas (1813–62) created the print room, which is lined with oak bookcases beneath an ornate plaster ceiling. Installed in 1859–60, its shelves were soon filled with albums and folders of prints and drawings. According to Alice de Quidt, assistant curator of Prints and Drawings at the Royal Collection Trust, it was some time before Queen Victoria was able to enter the print room after Prince Albert’s death, so full was it of her husband’s presence.

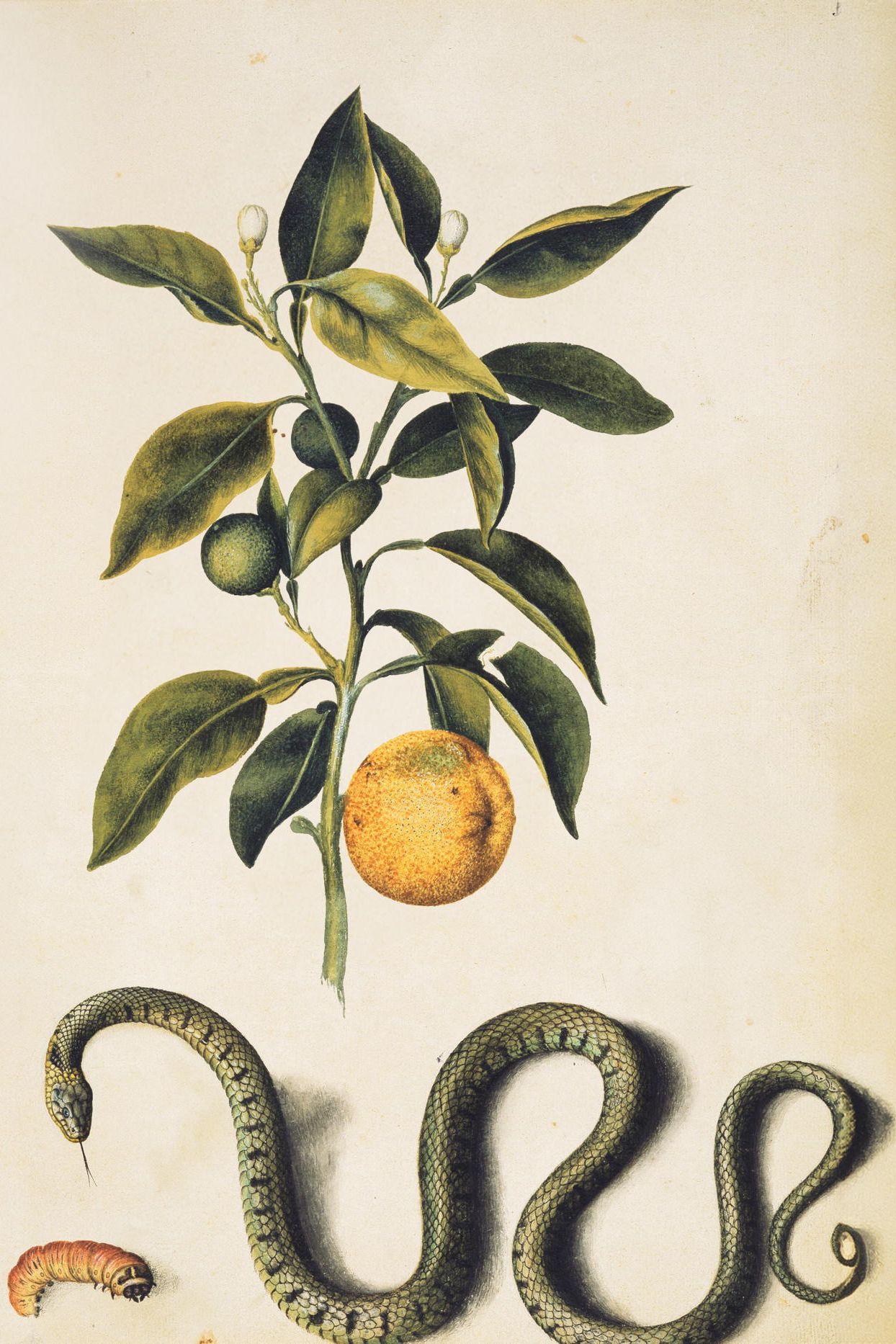

Seville orange, 1650–82, painted with grass snake and goat moth caterpillar.

Even the highest-quality reproductions cannot prepare one for the sight of Marshal’s original watercolours, most of which were painted on the best French and Italian papers. Some have watermarks, some the horizontal rope marks left from where the papers were hung to dry. Brilliant yellow and red-striped tulips, a giant sunflower, an almost-black iris and roses, softly petalled and painted from every angle, shine out from the stands where they have been arranged for us to see.

There is a naturalness in the works that comes as a surprise — yellow blemishes on a leaf are carefully recorded, holes left by a hungry caterpillar are rendered in detail, petals are painted where they fell. The brushwork is the finest a human hand could manage. Most startling is the juxtaposition of subjects. To give one example, a delicate little English wayside flower, the blue-eyed germander speedwell Veronica chamaedrys, is depicted almost touching the powerful head of the magnificent mourning iris, Iris susiana. The latter is native to the Lebanon of the eastern Mediterranean and would have been a highly prized import.

The evergreen hardy shrub Joseph’s coat and a white-flowered bottle gourd.

Although the bulk of the Florilegium had been completed by 1653, later additions were made from plants growing in the garden at Fulham Palace in west London SW6. This belonged to Henry Compton, Bishop of London (about 1632–1713), who lived there from 1675 and was both a keen botanist and a good friend of Marshal. They had first met in 1667, when Marshal became Compton’s steward at the Hospital of St Cross, near Winchester in Hampshire. Marshal moved with Compton to Fulham Palace and lived there — even after his marriage to Dorothea Smith three years later — until his death in 1682.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

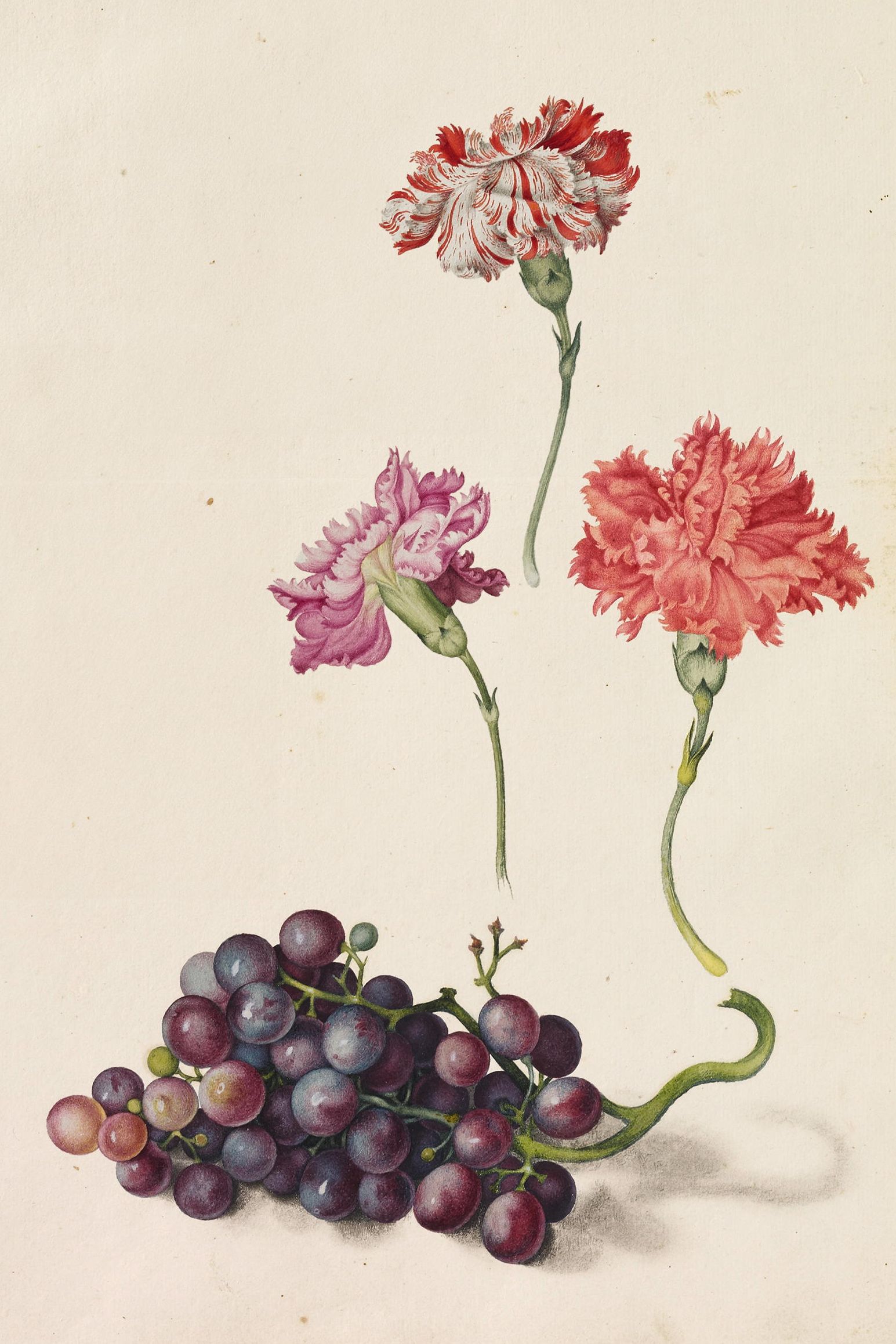

Three carnations: ‘La Princess’, ‘Damasquin’ and ‘Red Admiral of Zealand’, plus a bunch of Great Blue Grapes.

Marshal was born in exciting times, not only because new plants were being transported back from the Mediterranean, South Africa and the Americas, but also because he was painting during the reign of Charles I, the upheavals of the English Civil War and the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. We know he had been a merchant and had possibly lived in France, but it is sure that, by 1641, he was living in Lambeth with his friend John Tradescant the Younger (1608–62) and was painting on vellum a Florilegium of the flowers in Tradescant’s garden.

This was the garden the latter had inherited from his father, John Tradescant the Elder (about 1570–1638), who had been gardener to Queen Henrietta Maria and an avid collector of plants, art and foreign curiosities. The younger Tradescant followed his father as royal gardener and also travelled, bringing back plants from North America. Such foreign specimens were planted in the garden in Lambeth and were no doubt eagerly observed to see what miraculous flowers might burst forth from unprepossessing roots, tubers, corms and bulbs.

Clockwise from top left: Germander speedwell, mourning iris, broad-bodied chaser dragonfly, honeywort, bigroot cranesbill, turban ranunculus (double form) and flesh fly.

Close by was the Ark, which housed the Elder’s strange collection of artefacts from around the world and was the first museum in the country to open its doors to the public. Tickets were sixpence and gave entry to both the museum and the garden. (The Ark’s collection was the foundation of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.) Marshal’s Florilegium is noted by the Younger in 1656 in his Musaeum Tradescantium or A Collection of rarities preserved at South-Lambeth neer London as ‘A Booke of Mr TRADESCANT’S choicest Flowers and Plants, exquisitely limned in vellum, by Mr. Alex: Marshall’.

Sadly, that one didn’t survive, but we have Marshal’s own Florilegium, almost complete, in the Print Room at Windsor Castle. After Marshal’s death, it went to his wife, Dorothea, and was then left to his nephew, Robert Freind, headmaster of Westminster School, and thus to his son, William Freind. Noting a handful of missing pages from the Florilegium, the latter mentions ‘a Guernsey Lilly, which was cutt out of the Book by a Lady of great Rank at Chelsea, to whom my Father had lent it’. ‘It has been suggested,’ comments Prudence Leith-Ross in her introduction to The Florilegium of Alexander Marshal in the Collection of Her Majesty The Queen at Windsor Castle (Royal Collections, 2000), ‘that this was the first Duchess of Beaufort, whose family owned Beaufort House in Chelsea. She gardened enthusiastically both there and at Badminton in Gloucestershire.’

This dragonfly among the birds, dogs, lobsters and other creatures on this folio is one of 38 different insects that appear in the Florilegium. In his day, Marshal was as well known as an entomologist as he was a painter. His friend Samuel Hartlib variously referred to him as ‘the great-man for Insects’ and ‘Marshal the Gentleman for Insects’ having ‘a whole Chamber of Insects wch make a glorious representation’. His collection contained several hundred specimens, which he recorded in wonderfully observed studies.

The surviving pages were sold after Freind Jnr’s death at ‘Messrs Christie and Ansel on Friday, 25 April 1777’ making £52 10s and, by 1818, they had appeared in Brussels, where they were bought by John Mangles of Hurley, Berkshire. He reordered the paintings and had them rebound in two volumes, which he eventually gave to George IV. The date of presentation was not recorded, but Marshal’s masterwork was safe. Today, his paintings — and other prints and drawings in the collection — can be studied by researchers in the Print Room by appointment and on the website of the Royal Collection Trust.

‘Botanicals from the Royal Collection’ (£12.95) is available at Royal Collection Trust shops, as well as all good bookshops — www.royalcollectionshop.co.uk

Previously the Editor of GardenLife, Tiffany has also written and ghostwritten several books. She launched The Telegraph gardening section and was editor of IntoGardens magazine. She has chaired talks and in conversations with leading garden designers. She gardens in a wind-swept frost pocket in Northamptonshire and is learning not to mind — too much — about sharing her plot with the resident rabbits and moles.