The tourbillon watch is a masterpiece of order born out of tumult and disarray

What is it that makes the tourbillon — one the most beguiling instruments in watchmaking — tick?

One is expected to gasp with awe watching a SpaceX rocket take off and land back on its launchpad. Yet consider this: in 1795, without electricity, Abraham-Louis Breguet created a mechanism by candlelight to reduce the effects of gravity on a watch’s working parts — mitigating the number of slip-ups, delays and lost seconds that naturally occur on the dial.

Back then, a pocket watch sat vertically inside one’s jacket, which exerted pressure on its various components and risked sending the whole thing south. Breguet’s instrument, known as the tourbillon (French for ‘whirlwind’), tackled this vertical conundrum in the interest of accurate timekeeping. In the late 18th century, such precision — or lack thereof — could be the difference between setting sail for New York and ending up in Newfoundland.

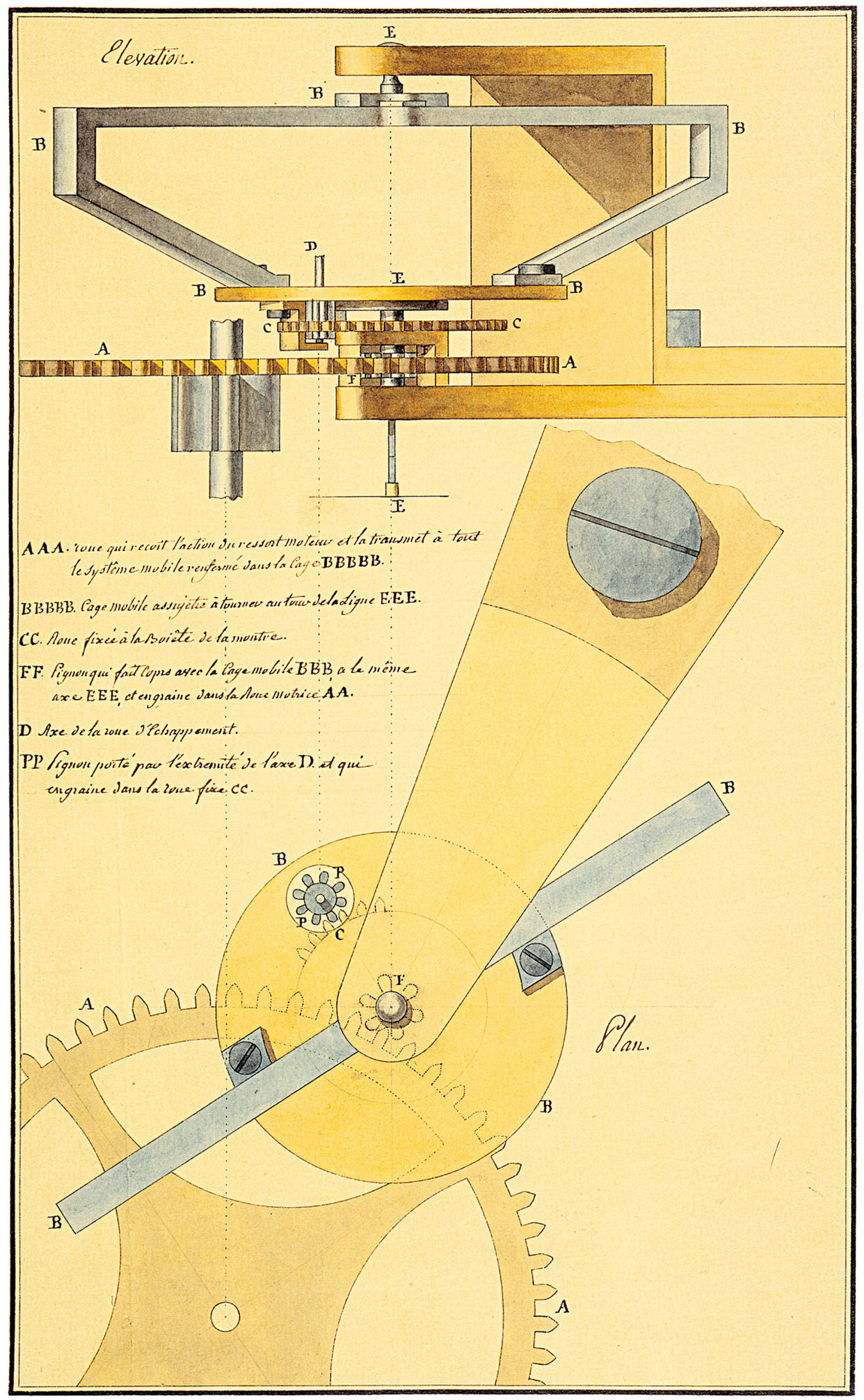

Exquisite engineering: Abraham-Louis Breguet’s development of John Arnold’s idea.

The late 19th century, however, saw the arrival of the wristwatch, an innovation that appeared to render the tourbillon obsolete. Even today, people may say that a modern watch’s sophisticated metals and advanced configurations have replaced the need for an internal mechanism designed to ensure accuracy. Yet the tourbillon is still considered a vital tool of the watchmaker’s arsenal, its inclusion pushing a price well into six figures. It is one of the most miraculous and important horological innovations in history.

The tourbillon dates back to John Arnold, inventor of the overcoil balance spring, and was honed by Breguet in the years after the French Revolution. The Paris-based Swiss watchmaker had long made watches for the aristocracy, as well as members of the French royal family, including Marie Antoinette. This was despite his revolutionary penchants; in the late 18th century, he was earmarked for the guillotine before fleeing back to Switzerland and then to England, where he worked for George III. It wasn’t until he went back to Paris that he invented the instrument that would cement his legacy: a masterpiece of order born out of tumult and disarray.

£208,300

The Tradition Fusee Tourbillon by Bregeut.

Looking at the tourbillon in more technical terms is no less labyrinthine. The device is a gyroscope, containing both the escapement and the balance wheel. The latter is the watch’s equivalent of a pendulum, whereas the former regulates the release of energy from the balance wheel to the mainspring — that is, the spiral torsion of metal ribbon that serves as the watch’s lifesource. The tourbillon usually occupies pride of place on the watch, with its own display space on the dial, and turns as the spring pounces back and forth — although the designers of Patek Philippe, high priests of complex watch-making, have chosen to conceal theirs.

It may be complicated, but, importantly, it is not a ‘complication’. In watch parlance, something qualifies as a complication if it adds a supplementary function to the host watch. The chronograph, for instance, serves as an independent stopwatch that tracks minutes at a time; a power reserve tells you when you need to wind the watch; a moon phase reveals, predictably, what phase the moon is in.

£192,600

More than 200 years after the mechanism was patented by Breguet, the company’s new Classique Tourbillon Sidéral 7255 is as finely balanced and deftly crafted as ever.

Between 1801 — the year the tourbillon was patented — and 1945, only 1,000 such watches were made. That scarcity, a result of the complexity and difficulty involved in building such a mechanism, lent it more legend. However, as gentlemen moved from pocket to wristwatches — smaller and thinner than their pouchy predecessors — a challenge arose for tourbillon watchmakers. How could they shrink such a complex apparatus into such a minuscule structure? How could the tourbillon wristwatch get the right feng shui to be both beautiful and practical?

It would need to fly. Proverbially, that is. In 1920, watchmaker Alfred Helwig of the Glashütte’s School in Germany made the first ‘flying’ tourbillon: a version of the instrument in which the rotating cage is supported only from below, creating an open, ‘floating’ appearance. Most tourbillons these days are of this kind.

The tourbillon is watchmaking at its most dextrous and skillful. Since the 1980s, luxury brands have used the device for bragging rights, increasing their complexity and unlocking new ground. In 1986, Audemars Piguet released the Calibre 2870 ultra-thin tourbillon, a paean to the applied arts writ large. By tucking the tourbillon into a tighter space than it had ever sat in before, it was then the thinnest of its kind, as well as the first ever automatic tourbillon wristwatch. The brand has since continued to push boundaries, notably with the recently announced RD #5, a tourbillon chronograph designed to fit into its renowned Royal Oak ‘Jumbo’ Extra Thin.

Another groundbreaking moment came in 2005, when Greubel Forsey made a quadruple tourbillon, featuring four individual tourbillon cages, each containing a balance wheel and hairspring, all within the same watch. Also of note is Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Reverso Tribute Duoface Tourbillon from 2023, where the device is visible from both the front and back of the watch. Girard Perregaux is significant, having created a double-axis tour-billon; Jaeger-LeCoultre has made a triple-axis edit. Breguet, too, is still doing its founder proud, releasing the Classique Tourbillon Sidéral 7255 this year. This is only the fifth time a Breguet tourbillon has been available to buy, joining ranks with legends such as the Marine Tourbillon Équation Marchante 5887.

Price available upon request

The Reverso Tribute Duoface Tourbillon by Jaeger-LeCoultre.

Today’s innovations are solving new tricks, as well as older ones. Earlier this year, I had the pleasure of flying to Los Angeles, US, to witness the unveiling of the resurrected Urban Jürgensen, an old Danish brand helmed by Alex Rosenfield and the highly respected Kari Voutilainen — 10 of whose watches have won the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève. Inside the UJ-1, the first of three watches presented at this event, was hidden a wonderful tourbillon with a remarkable extra component: a spring remontoir d’égalité, which provides constant force to the escapement and optimises the watch’s energy consumption. One often forgets how much energy a watch consumes, with power stored in the barrels and released into the various components upon operation. The tourbillon is among the highest-consuming elements of a watch, yet the addition of a remontoir tempers its expenditure and gives the UJ-1 more time between winds — 47 hours, to be precise. Imagine an iPhone lasting that long.

If necessity is the mother of invention, nostalgia might be what keeps the flame alive. ‘My first tourbillon was a Breguet,’ says Ahmed Rahman, one of the most discerning watch aficionados in the world, whose personal collection includes several tourbillons. His love of the instrument comes down to ‘the history and innovation’. ‘If I could only keep one of them,’ he says, ‘it would be the Breguet.’

There will always be an appetite for the tour-billon, British watchmaker Roger S. Smith told Hodinkee Magazine; one that transcends any actual need for it as a timekeeping tool. It adds no more accuracy than a smartphone; its value lies in romance of history and craftsmanship. The tourbillon may no longer determine a ship’s safe landfall, yet it still turns with a noble purpose: a small, whirring testament to man’s mastery over Nature’s pull.

Tom Chamberlin is the editor-in-chief of The Rake magazine, host of The Luxury Dispatch podcast (launching December 2, 2024), author of Huntsman: Redefining Savile Row, and is an accidental TikTokker. He writes on style, culture and craftsmanship with a British sensibility and a deep respect for heritage and the artisans that carry on the cause.