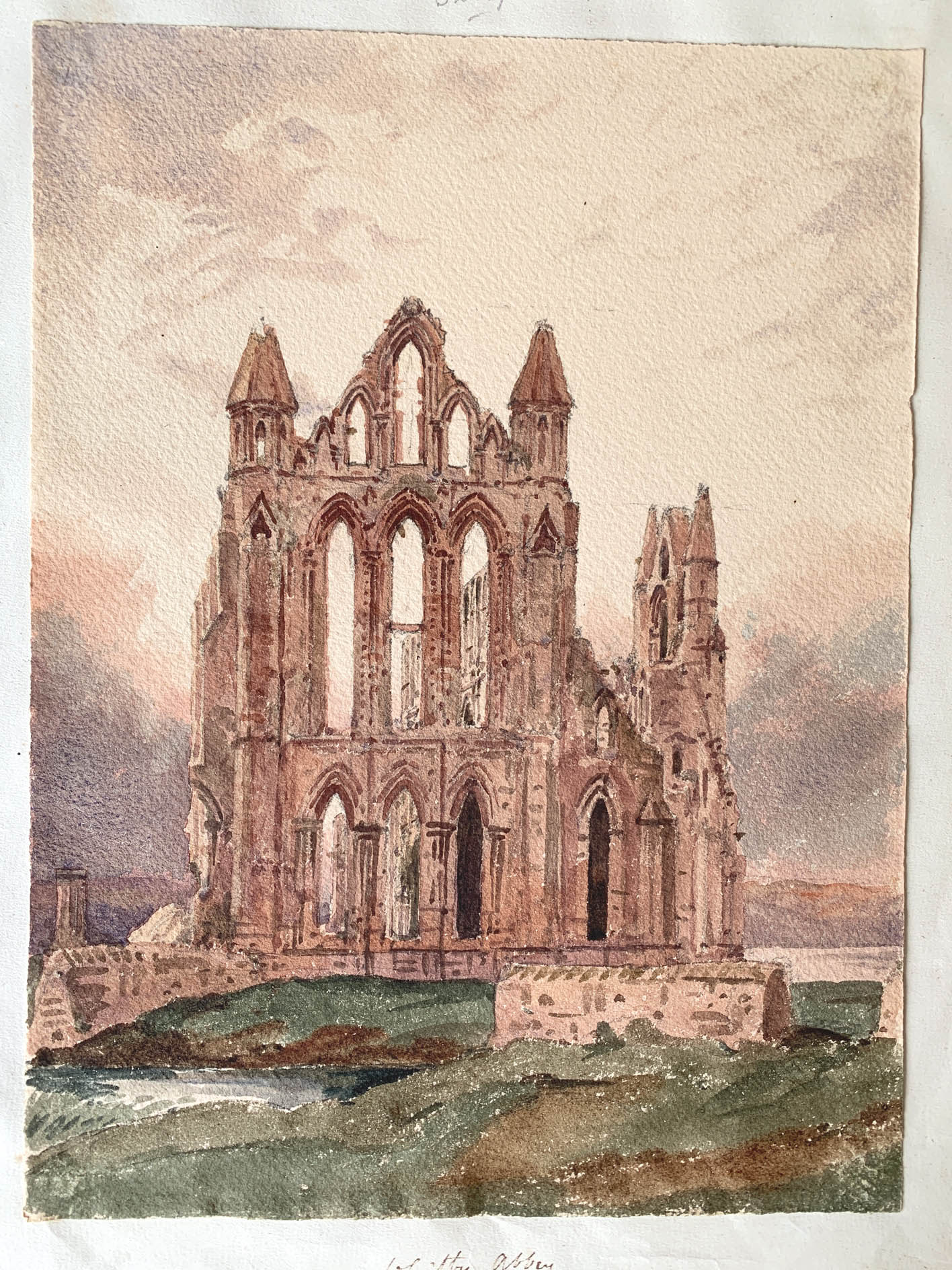

In Focus: Britain's forgotten impressionist, whose works of genius lay undiscovered in an attic for over a century

How does art endure? The painter John Louis Petit had no need to sell, did not exhibit his work professionally and most of it was forgotten until the death of his grandniece.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How could anyone not warm to an author whose first book opens: ‘The following pages contain no more than they profess, namely, remarks upon Church Architecture, such as might be made by one who has taken more pleasure in a pursuit, and is willing to persuade his conscience that the hours he has given to his own gratification have not been altogether misemployed’?

The book in question is Remarks upon Church Architecture by John Louis Petit. Born in 1801, he was a member of a distinguished Huguenot family that included soldiers, vicars and philanthropists, but good marriages brought them greater prosperity through estates with reserves of coal and limestone. His grandfather was a noted physician whose career continued beyond death: ‘I desire my body may be opened [for medical science] if the distemper of which I may die shall not have rendered it so loathsome as to endanger the operator and that the sum of ten guineas shall be given to the person who shall perform the operation.’ His other — non-Huguenot — grandfather was John Astley (1724–87), portrait painter, amateur architect, ‘a gasconading spendthrift and a beau of the flashiest order’.

Much of the family wealth descended to Petit, which meant that, although he had been ordained in 1825, after Eton and Trinity, Cambridge, in less than 10 years he was able to retire from his curacies in Essex and devote himself to art and church architecture.

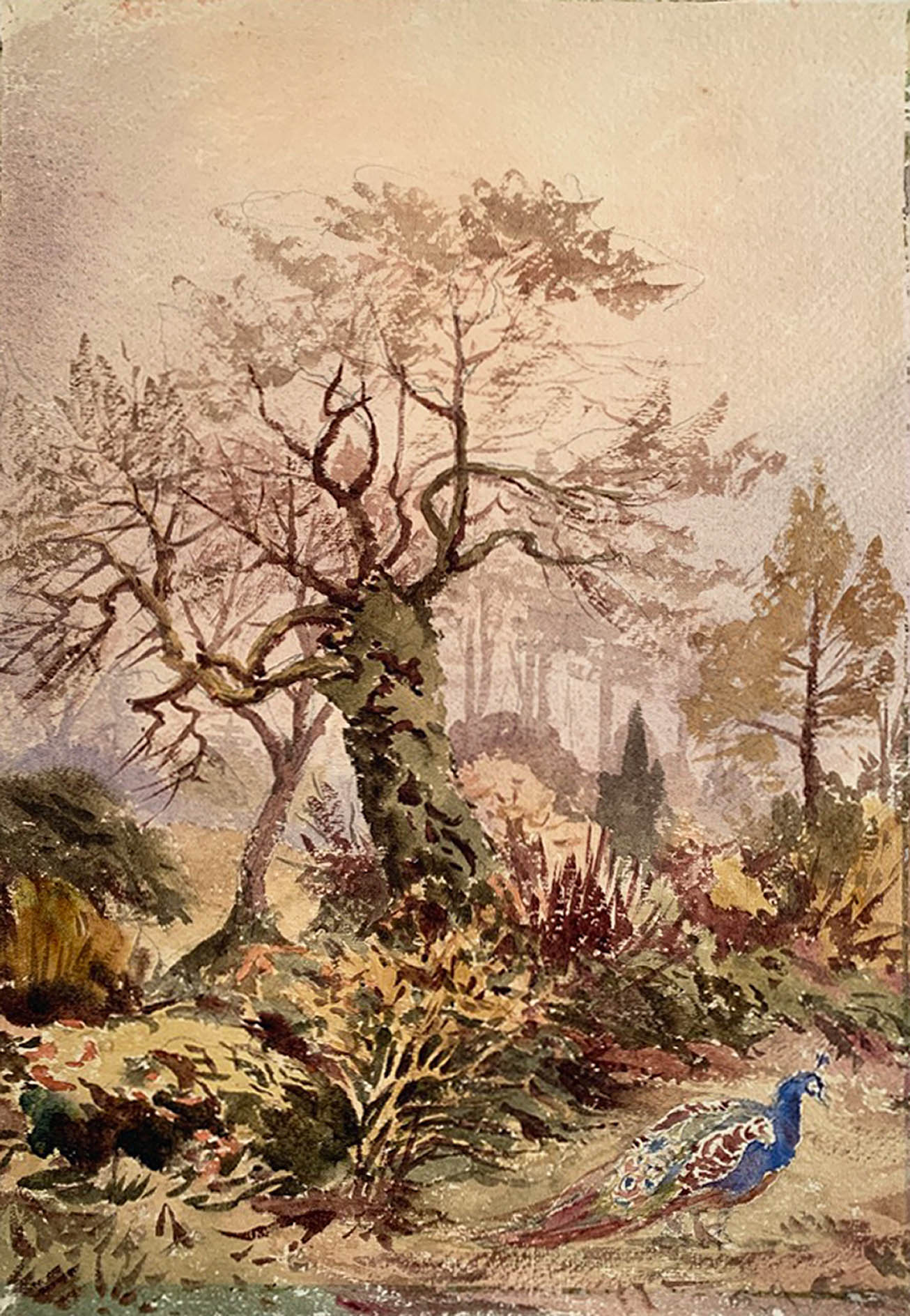

It is not certain who taught him to use watercolour so skilfully. His friends included Samuel Prout, 20 years his senior, whose work he copied before developing his own style, and the watercolourist and photographic pioneer Philip Henry Delamotte, 20 years his junior. It is possible that the latter’s father, William Alfred Delamotte, drawing master at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, may have taken a hand in Petit’s artisticformation. Peter de Wint, perhaps the most successful drawing master of the time, certainly seems to have been an influence and, on occasions, Petit’s early style is reminiscent of the Constable follower Agostino Aglio. Later, it became ever more free and, indeed, Impressionistic.

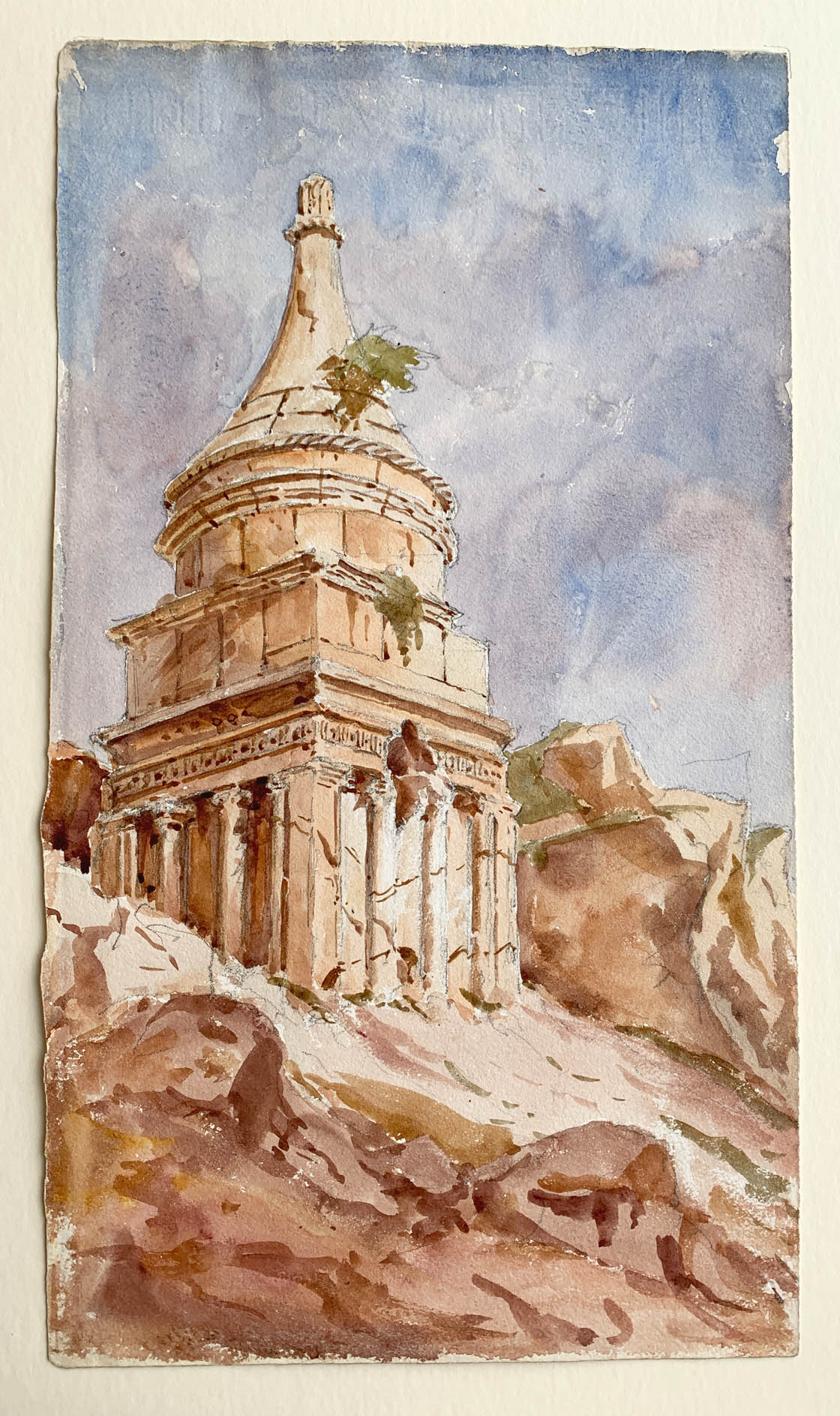

Petit had been a hard-working curate and it is well that he abandoned that career — otherwise, he could not have become such an indefatigable landscape draughtsman and recorder of buildings in Britain and abroad, leaving a total of perhaps 15,000 watercolours and pen drawings. Unfortunately, however, he was often accompanied on his travels by some of his relatives, who worked in his manner. Neither he nor his sisters — Elizabeth, Susannah, Maria and Emma — nor his sister-in-law Amelia Reid and niece Sarah Salt usually signed, so it may only be quality that suggests who did what. In this, he was like Hercules Brabazon Brabazon, another innovative amateur who travelled with a ‘harem’. Luckily, Petit’s wife Louisa preferred still lifes.

In 1841, that first book, Remarks upon Church Architecture, propelled him to public notice. Initially inspired by Charles Barry and A. W. N. Pugin, and driven by the Cambridge Camden Society and its journal, The Ecclesiologist, the Gothicising fashion was carrying all before it, with routine ‘scraping’ of original plastered interiors beginning in the 1840s and running on through the century.

In Remarks, Petit mounted a counter-attack on savage restorations carried out in the name of doctrinaire purity: ‘But alas for the building which falls into the hands of an ignorant or presumptuous restorer! I do not speak under the influence of any strong antiquarian feeling… but it is truly grievous to see the proportions of a beautiful edifice needlessly defaced, or the character stamped upon it by artists who worked upon rules nearly as unerring as those of instinct, swept away by persons who know such rules only as are dictated by their open caprice and fancy, or at best suggested by a very limited course of observation.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Unsurprisingly, this provoked a bout of aesthetic and intellectual fisticuffs quite as fierce as that engendered by the pre-Raphaelite explosion at the end of the decade — and Petit held his own. Sir George Gilbert Scott was one of his prominent targets, but, in 1873, Scott’s son would write of the ‘numbers of fine old churches [that] have been stripped internally, and reduced to a nakedness compared with which Puritan whitewash is decency’.

In a fold of the mountains between Barmouth and Bontddu in Wales is a church of extraordinary individuality and importance, Petit’s only surviving architectural essay, his house for himself having been demolished. St Philip’s Chapel, Caerdeon, which he built for a brother-in-law, is hard to define. It has been variously described as rustic Mediterranean, Alpine, of French Basque influence or like an Italian farm building. Naturally, The Ecclesiologist was not impressed, dismissing it in 1863 as ‘something between a large lodge gate and a lady’s rustic dairy’. It was almost allowed to sink into a picturesque ruin, but, thanks to heroic efforts by the Friends of Friendless Churches since 2019, working whenever permitted by lockdowns, it has now been stabilised. For the moment, it seems safe and Philip Modiano and others are bringing Petit into the light as a most accomplished and interesting artist.

After 486 pages and uncountable drawings ranging widely over England and the Continent, our author ended his Remarks with a vale equal to his ave: ‘And here, reader, I bid you farewell. Should you start on a less beaten or more comprehensive tour, whether the object of your pursuit be architecture, or scenery, or science, or natural history, or costume, or the study of men and manners, I wish you pleasant companions and all manner of happiness and success.’ What a pleasant companion he must have been.

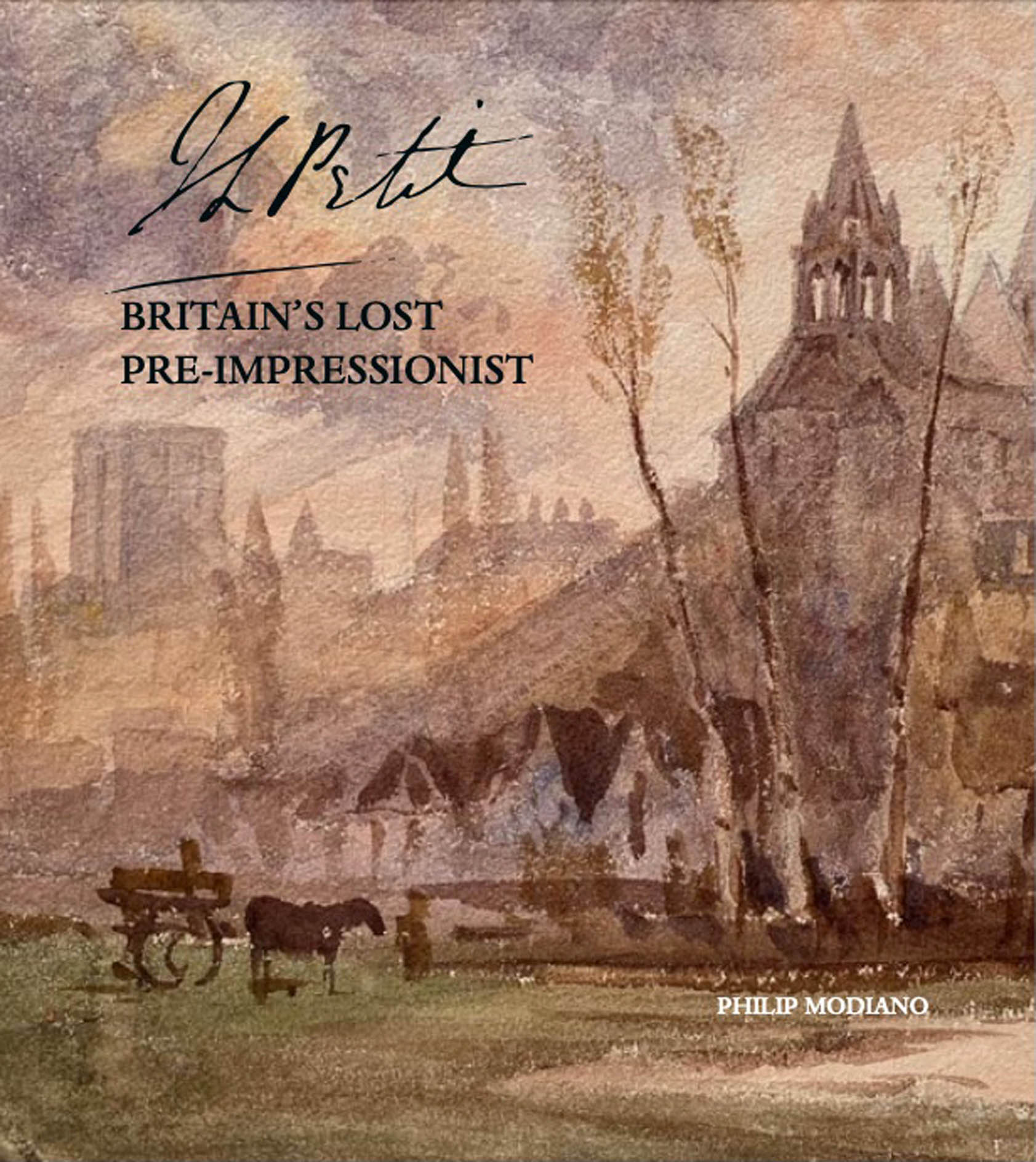

Philip Modiano's J. L. Petit: Britain’s Lost Impressionist is published at £20 by RPS Publications — see revpetit.com for details and to order.

In Focus: How Italy inspired JMW Turner

Mary Miers considers how the country that fascinated Turner from youth shaped his artistic vision.

Credit: Getty Images

In Focus: John Hassall's iconic travel posters

The works of British poster king John Hassall remain a breath of fresh seaside air, says Lucinda Gosling.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

In Focus: Bernardo Bellotto, the Canaletto of the North

Being the nephew of Antonio Canaletto was both a blessing and a curse for Bernardo Bellotto, whose brooding landscapes eventually

In Focus: The breathtaking nature photography of David Yarrow

Renowned British photographer David Yarrow has spent decades capturing some of the planet’s most endangered species in their natural habitats.

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.