In Focus: How mass tourism to the seaside produced an entire era of iconic Modern art and architecture

Clive Aslet examines how seaside resorts used Art Deco to catch the eye, spurring on a movement of Modern designs for health and beauty.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Does anyone still have a beach cape? If so, Ghislaine Wood, curator of the Sainsbury Centre’s new exhibition, would like to hear from you. Beach capes – voluminous, tent-like robes that allowed the (female) wearer to change into a swimsuit without any loss of modesty – were an essential accessory of the 1930s seaside.

Brightly coloured and strikingly patterned, these once ubiquitous garments seem to have been thrown out, together with the knitted bathing dresses over which they were worn, once fashion changed. Elaborate evening dresses had a more obvious value; the exhibition contains some sleek and shimmering examples borrowed from South-end Museums. (One of the aims of the show has been to draw on out-of-London collections.)

Architecturally, Art Deco found a natural home at the seaside. Bold, eye-catching and cheap to build, it was particularly suited to cinemas, lidos and hotels. There were some masterpieces, such as Oliver Hill’s Midland Hotel in More-cambe, Serge Chermayeff and Erich Mendelsohn’s De La Warr Pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea and Joseph Emberton’s Blackpool Pleasure Beach – not that the architects would have seen themselves as working in the Art Deco style, as the term was only coined in the 1960s. Billy Butlin’s first holiday camps (Skegness, 1936; Clacton, 1938) used the style to catch the eye of the middle classes.

The exhibition examines such works against the background of a wider visual culture that embraced paintings, furniture, light fittings, travel posters, railway engines and clothes.

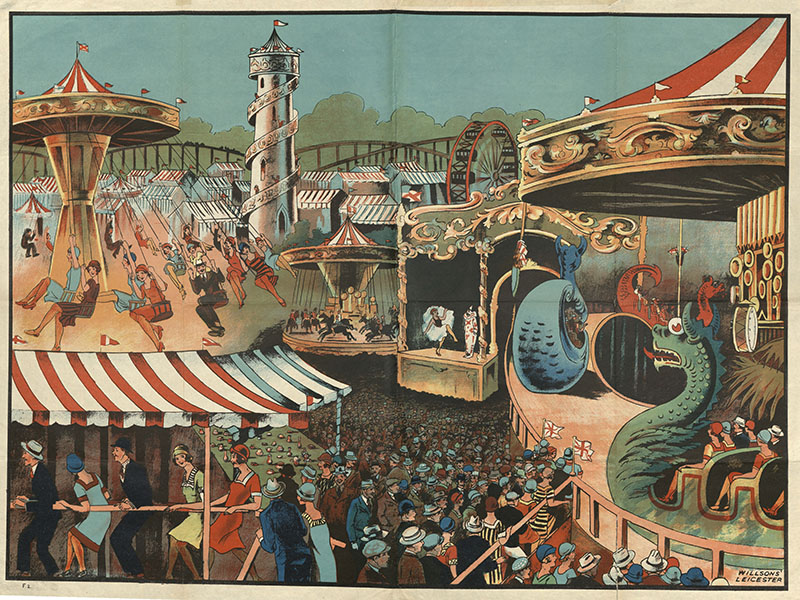

There was no Art Deco manifesto. At the super luxurious end – represented by Jean Dunand’s Clair de Lune screen depicting a moonlit seascape in the sumptuous lacquer technique he had learnt from a Japanese master – it relates to the 1925 Exposition des Arts Decoratifs held in Paris. But the net is thrown wider than that to catch artists, often living by the sea, such as Dod and Ernest Procter, depicting the faceted roofs of Newlyn in Cornwall in a style derived from Cezanne, or a fairground scene, crowded with incident, inspired by the paintings of Bruegel. Conservative Modernism, with a preference for realism over abstraction, is the note.

Being popular and undoctrinaire, Art Deco could adapt itself not only to mass leisure and tourism, but to the inter-war preoccupation with hygiene and health. For people who passed their lives in the grime of smoke-blackened, under-maintained cities, the breeziness of Art Deco – lit inside and out by electricity – offered the hope of a new way of life.

Sunshine and fresh-air were antidotes to disease. A painting by James Walker Tucker, Hiking, shows three rucksack-bearing young women, dressed in shorts, studying a map in the countryside; it could not have happened a generation before. Mary Bagot Stack founded the Women’s League of Health and Beauty to promote her ‘stretch-and-swing system’ of physical exercise; a fascinating catalogue essay reveals that she developed her ideas after observing the better posture of yoga-practising women in India, where she had lived.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Members performed their drill outdoors, wearing a slinky uniform of black satin shorts and white sleeveless satin blouse that combined the need for ‘skin-airing’ with Hollywood glamour. Stack’s daughter, Prunella, met her future husband, Lord David Douglas-Hamilton, after making the dive that opened a swimming pool in Scotland. Furniture made of tubular steel or bent plywood also promoted health: germs had nowhere to hide.

Some design-conscious industries found themselves at the seaside almost by chance. In Dorset, Poole Pottery, evolving from an older ceramics company, made glazed earthenware vases and plates decorated with patterns that recall the colourful Russian folk and peasant idiom of the Ballets Russes. Alec Walker established Cryséde Silks at Newlyn, where his wife, Kay Earle, belonged to the artistic community.

The success of its hand-blocked fabrics allowed it to expand into a disused pilchard cellar at St Ives. EKCO, which became one of the most successful electronics manufacturers in the world, operated from Southend-on-Sea because that was where its founder, E. K. Cole, had grown up. In the 1930s, Cole was quick to see the potential of Bakelite, a kind of moulded plastic.

Designed by Welles Coates, the EKCO wireless model AD-65 was contained in a circular case, the geometry of which would have been impossible to achieve on a mass scale in wood. Listeners were proud to put their modernity on show in their front rooms. Art Deco, slightly tawdry at times, could also be aspirational.

‘Art Deco by the Sea’ is at Sainsbury Centre, University of East Anglia, Norfolk Road, Norwich, Norfolk, until June 14. It is accompanied by a book of essays and will run at the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle, July 11–October 11.

In Focus: The Spanish painter whose visceral depictions of martyrdom still have the power to shock

The unflinching representations of brutality in Jusepe de Ribera's images of martyrdom is the focus of a new exhibition, the

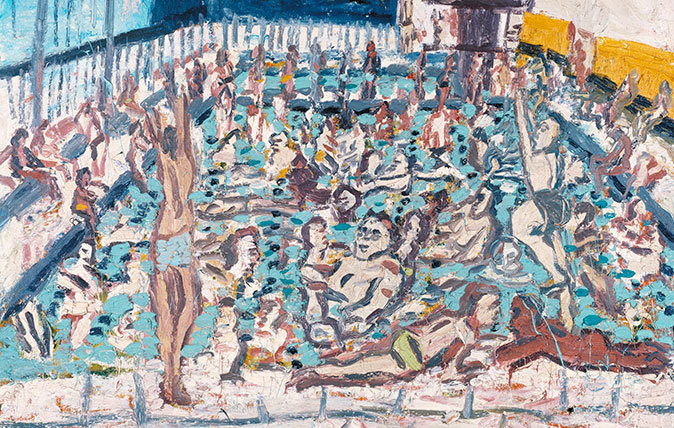

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show

Credit: ©Paul Highnam/Country Life Picture Library

In Focus: The greatest Victorian houses in Britain, as featured in a magnificent one-off magazine

In Focus: The Pre-Raphaelite sisters who fought for recognition in the shadow of the Brotherhood

Caroline Bugler admires the National Portrait Gallery's new exhibition, 'The Pre-Raphaelite Sisters', which reveals the creative role of women in

In Focus: How Christina Rossetti's poetry spilled over into the world of art

One of our great Victorian poets had an impact far beyond the words she committed to paper. Jeremy Musson takes

Credit: Getty Images/EyeEm

In Focus: How the belt of a goddess revealed the true colours of the Parthenon marbles

For nearly 200 years the Parthenon marbles held onto the secret they were suspected of keeping.