Curious Questions: Why do we call a waterproof rain coat a mackintosh?

Scotland has turned out endless inventors of great genius in the past few hundred years, and Charles Macintosh — the man who brought waterproof clothing to the world — was as successful as any of them. Martin Fone tells his story.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

'Where there's muck, there's brass', 'where there's muck, there's money', ‘muck and money go together’... No matter which way you've come across the old adage, its meaning is as clear as ever it was.

The phrase was first recorded (in the third of those forms) by John Ray in A collection of English proverbs (1678) — and it might well have served as the Macintosh family motto. Father George, a dye manufacturer, sent round collectors to pay the poorer denizens of Glasgow for their urine, from which he extracted ammonia. This he used in the manufacture of cudbear, a valuable violet-reddish dye obtained from lichens, which his son, Charles, supplied from Europe.

By 1786 when he was twenty, Charles had branched out on his own, opening a factory in Glasgow producing ammonium chloride and Prussian blue dye. A chip off the old block, he would collect soot and urine, from which he extracted salt. His ability to extract alum from waste shale from the area’s coal mines led him to establish Scotland’s first alum works at Hurlet in Renfrewshire in 1797, introducing the manufacture of lead and aluminium acetates to Britain.

It was his collaboration with Charles Tennant, the owner of a chemical works at St Rollox, just outside Glasgow, that made his fortune. Hitherto, bleaching textiles involved boiling them in a weak alkali solution and then exposing them to sunlight for months, a process that was both time-consuming and expensive. In 1799, with the assistance of Macintosh, Tennant created a bleaching powder from the chemical reaction between chlorine and dry slaked lime.

The powder, effective, relatively cheap, and easily transportable, was commercially successful, transforming the textile industry and, by the 1830s, making the St Rollox chemical works the largest in Europe. Bleaching powder was used industrially to bleach cloth and paper well until the 1920s.

Macintosh soon spotted another opportunity from another seemingly unwanted waste material, the tar sludge created from the manufacture of coal gas used to power the new-fangled gas lighting that lit up public thoroughfares and the homes of the well-to-do in the early 19th century. In 1819 he contracted with the Glasgow Gas Company to buy all their waste product. They were only too happy to oblige.

Charles discovered that he could distil the tar to produce a volatile, oily liquid hydrocarbon mixture known as naphtha. While it could be used for flares, Charles continued to experiment to see whether naphtha could be used for even more useful and profitable purposes. His light-bulb moment came when he discovered that it could dissolve India-rubber.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

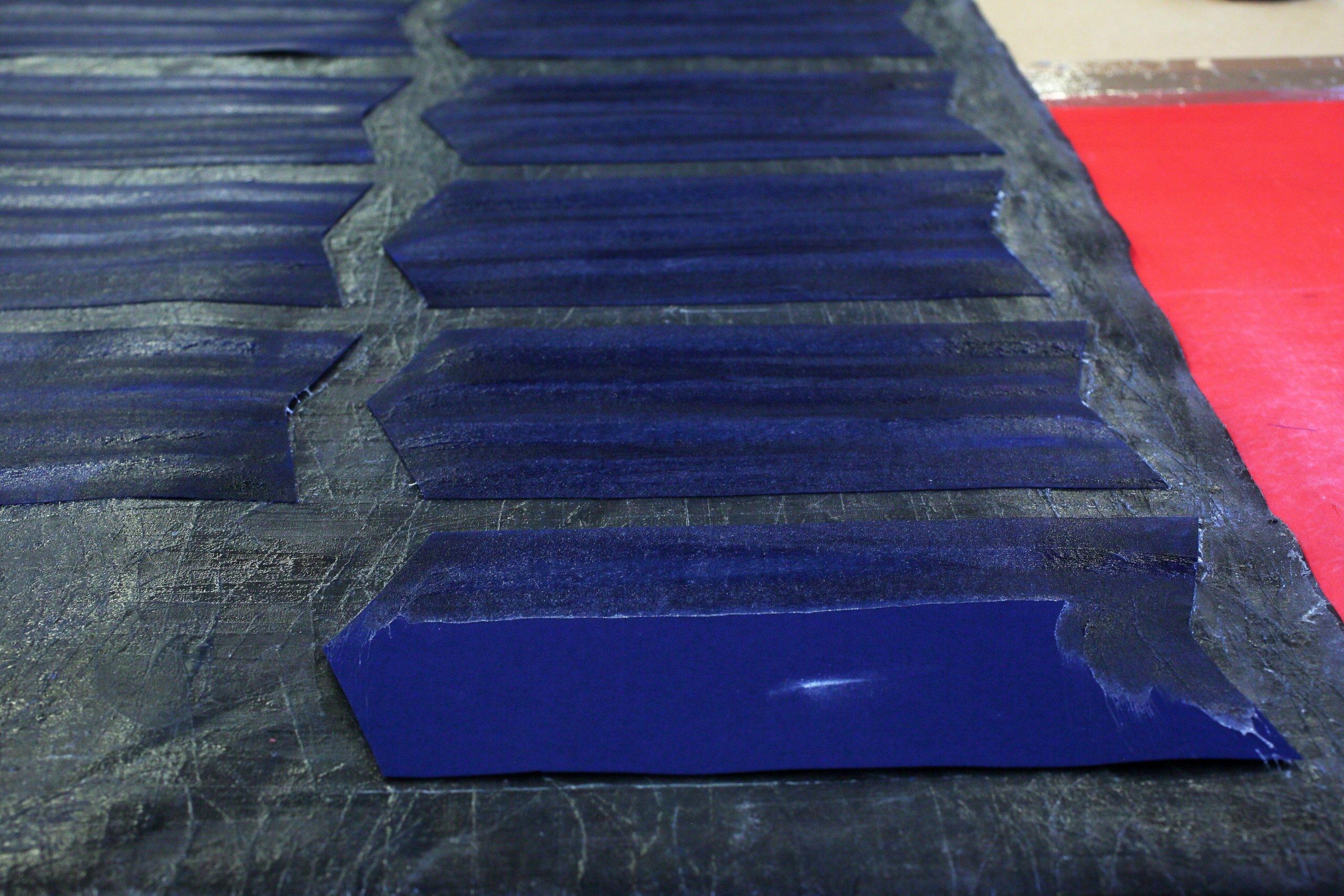

By pressing a solution of India-rubber dissolved in naphtha between two layers of fabric rather like a sandwich, Charles found that the rubber interior formed a barrier that was almost completely water resistant and yet left the fabric flexible enough to be used in a garment. It did not take long for a man with his finely attuned commercial acumen to realise that for those exposed to the vagaries of the British weather a coat that was truly waterproof was manna from heaven.

On June 17, 1823, Charles received a patent (No 4804) for a process ‘for rendering the texture of hemp, flax, wool, cotton, silk, and also leather, paper and other substances impervious to water and air’. Reports suggest that the first coat made from Charles’ material was sold in Glasgow on October 12, 1823, less than four months after he had received his patent.

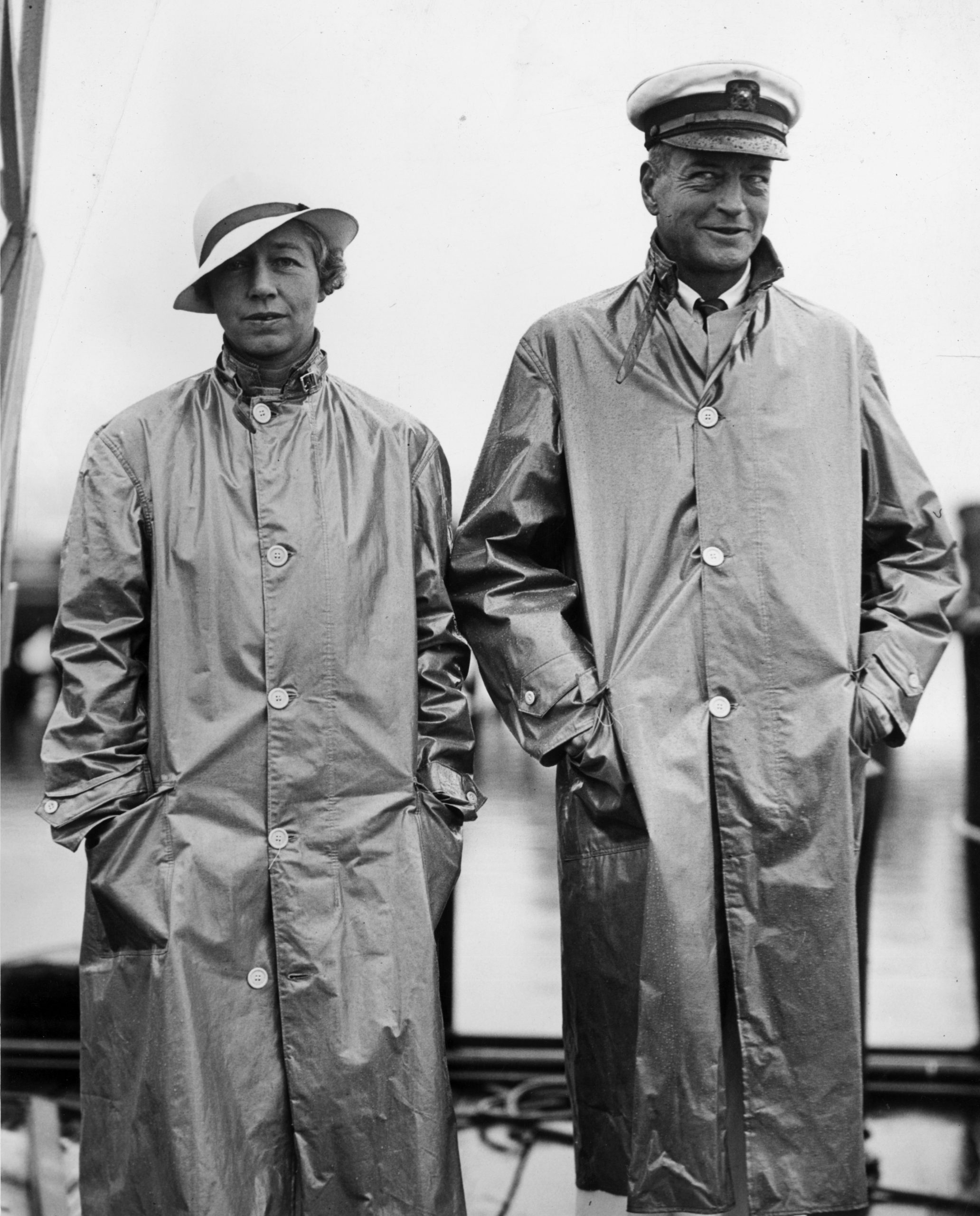

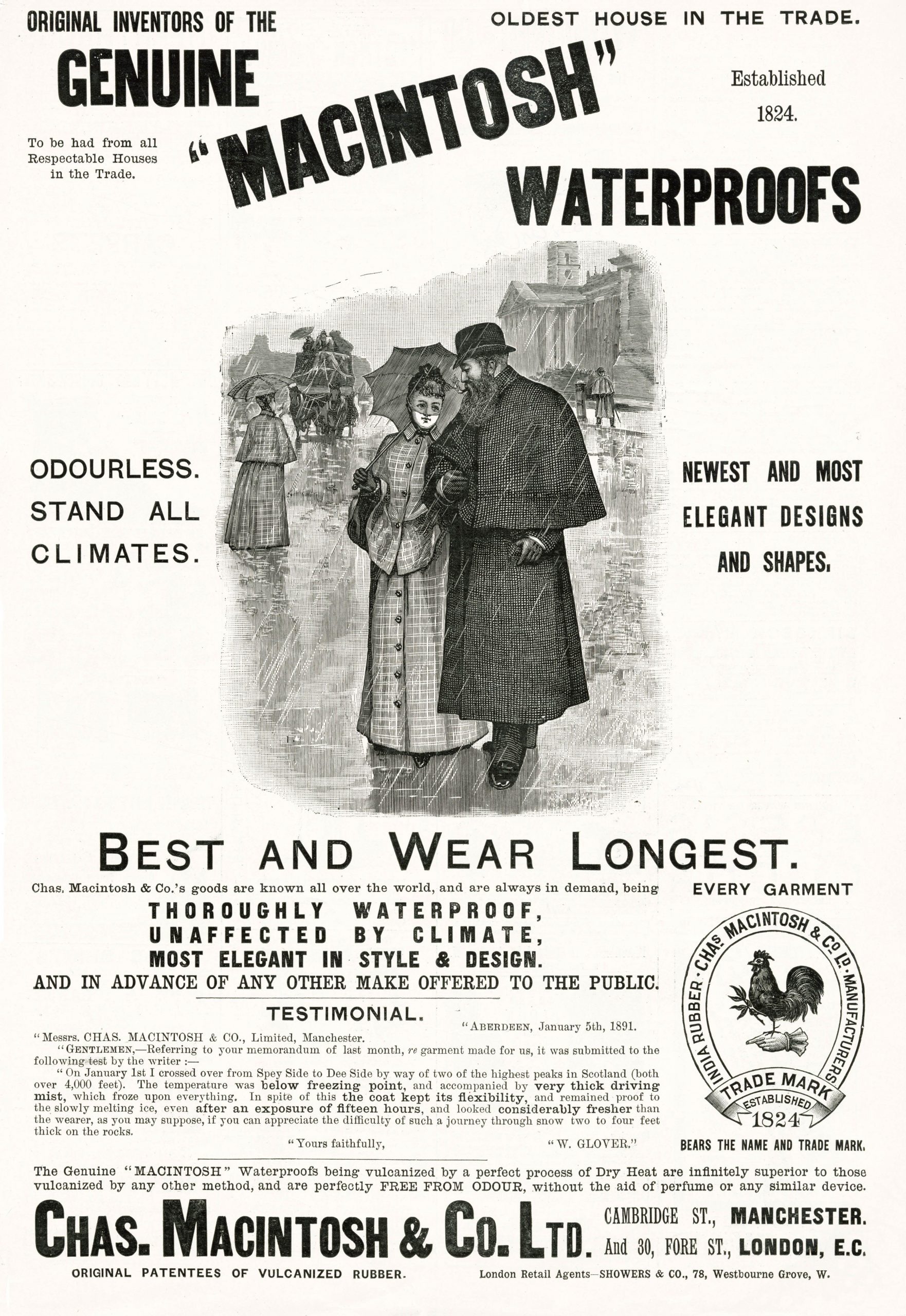

At first, Charles just produced the cloth, leaving tailors in Glasgow and then London to fashion it into garments. Initial reactions were mixed. Tailors found the material difficult to work with. Customers found that while the coats were undeniably waterproof, they became stiff in the cold, tended to become sticky in the heat, and gave off a strong, unpleasant smell. The rubber layer would leak through stitching holes and would deteriorate rapidly when it met the natural oils of wool. Nevertheless, Charles scored some notable early successes, including equipping the crew of Sir John Franklin’s 1824 Arctic expedition with waterproof garments.

Thanks to Thomas Hancock, Macintosh was able to solve the problem of the material’s unpleasant odour and sensitivity to temperature. A pioneer of rubber technology, Hancock had invented a ‘masticator’ in 1819 which transformed scraps of rubber into blocks or sheets and, in 1825, a process to produce artificial leather with masticated rubber.

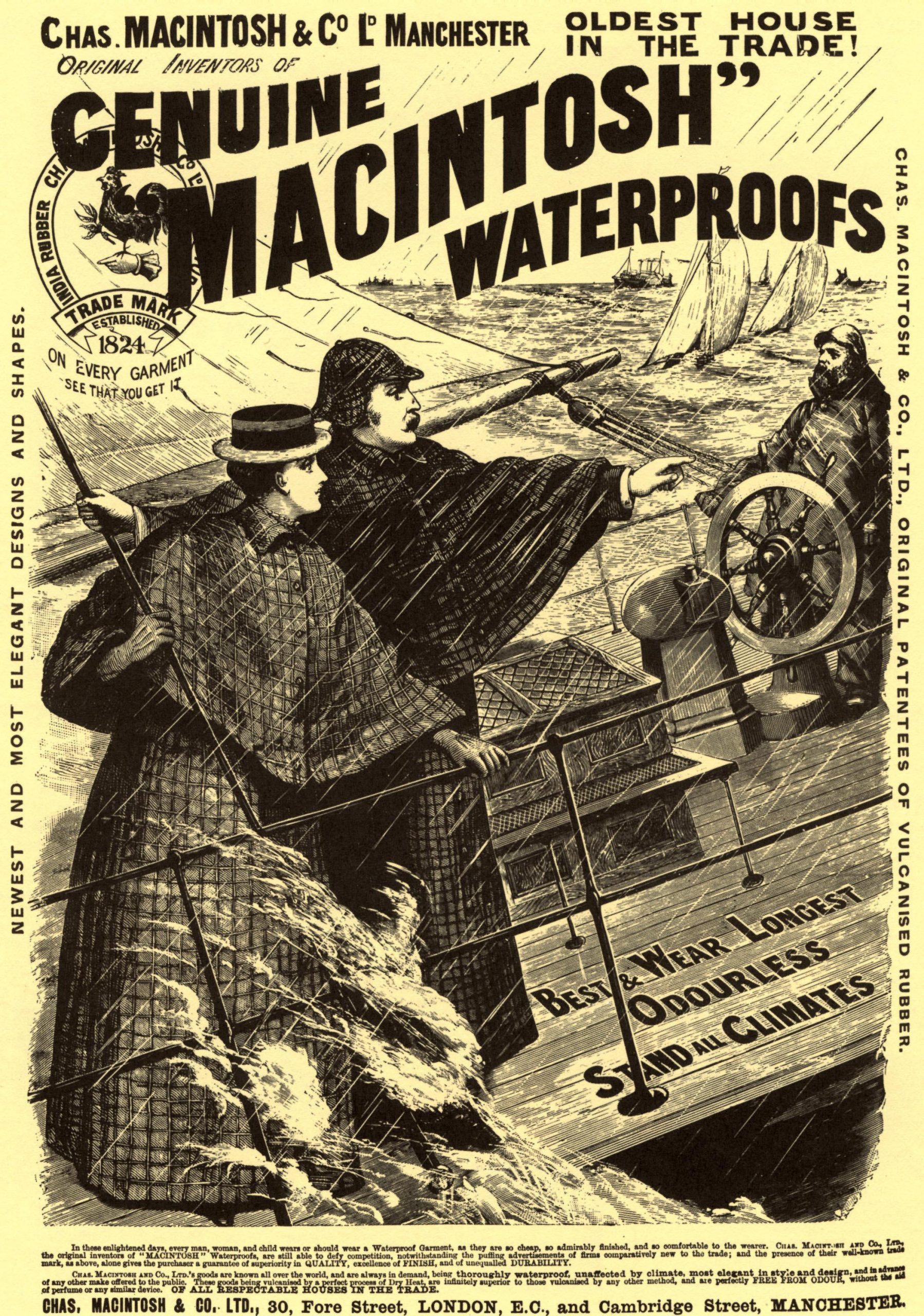

The acknowledged superiority of the fabric produced by Hancock’s process led to the two men agreeing to collaborate by 1830, merging their businesses, and opening a factory in Manchester where garments were made. They also developed an automatic spreading machine which replaced Macintosh’s paint brushes. It was only in 1837 when Macintosh’s patent had expired that Hancock patented his masticator and spreader (no 7344).

Perhaps Macintosh’s greatest early commercial success came in 1841 when the British army placed an order to equip all its troops with waterproof clothing. So functional and hard wearing was it that it soon became standard army issue.

The company’s fortunes temporarily dipped after Macintosh’s death in 1843, curiously in part due to the boom in rail travel. Enclosed railway carriages instead of exposed horse-drawn coaches meant that the hardy traveller barely had to protect themselves against the weather.

It was just a temporary blip, a successful appearance at the Great Exhibition of 1851 rejuvenating the fortunes of Macintosh’s material to such an extent that his name became the portmanteau word for all rainwear, even if the insensitive Sassenachs had inserted an unwanted k into it.

Macintosh, though, was not the first to recognise that a rubber solution could repel water. Fellow Scot, surgeon and chemist, James Syme had noted, as he described in a letter written on March 5, 1818, and published in Thomson’s Annals of Philosophy, that ‘as coal tar in every respect bears the strongest resemblance to petroleum, it occurred to me that by distilling it a fluid might be procured which, like naphtha, should have the property of dissolving caoutchouc [natural rubber]’. His account detailed his success in producing ‘a valuable substance which may be obtained from coal tar’ and concluded by hoping that his discovery would extend ‘its use to the many purposes for which it is so peculiarly well adapted’.

A surgeon at heart, Syme did not pursue the idea further, but his process was identical to that which Macintosh patented five years later, leading to suggestions that Macintosh had familiarised himself with Syme’s work before conducting his own experiments. There was once crucial difference though; Syme had not considered the concept of sandwiching a layer of rubber between two layers of fabric.

Even that was not unique to Macintosh. The Aztecs had used natural latex to waterproof fabrics, an idea adopted by Spanish scientists who used a rubber lining to leak-proof containers used to store mercury. The eminent British balloonist, Charles Green, had made a balloon envelope that was waterproofed with a rubber inner in 1821, a variation on the French practice of making the fabric of their balloons gas tight by impregnating it with rubber dissolved in turpentine.

Macintosh’s genius was to pull together these various strands, making a fabric that was not only truly waterproof but also easy to fashion and to wear and exploiting it commercially for all he was worth. That macs are still part of our wardrobe after two centuries is worthy of celebration.

While we still have his coats, however, we no longer have his name. Over the years the Macintosh picked up an extra 'k' in the middle of the name, with even the original company — which is still going to this day — changing its name to Mackintosh.

It's probably no bad thing: at least it means that you won't end up buying an Apple computer when all you wanted was to keep dry in a rainstorm.

Curious Questions: Why do Australians call the British 'Poms'?

With England about to take on Australia in The Ashes, Martin Fone ponders the derivation of the Aussies nickname for

Curious Questions: What is a 'doubly-thankful' village — and how did Upper Slaughter become one?

Martin Fone examines the (sadly rare) phenomenon of the parishes who erect memorials not to the fallen, but to those

Curious Questions: Why were ferns considered magical?

Martin Fone considers the beautiful and ancient fern, once commonly held to have mysterious properties.

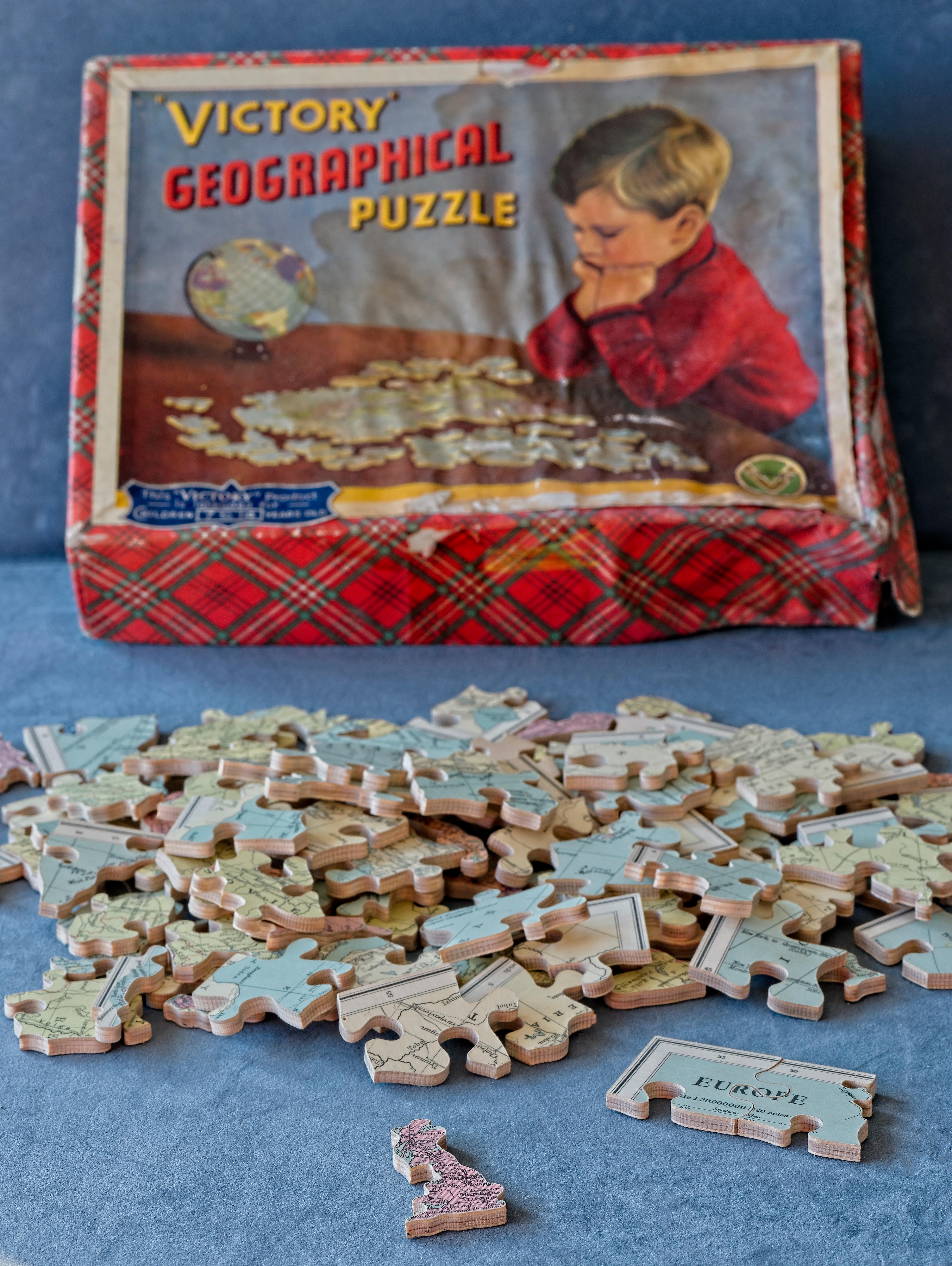

Curious Questions: Why do we call picture puzzles 'jigsaws'?

Jigsaws have been around since the 18th century and have gone through all sorts of iterations. Martin Fone traces their

Credit: Alamy

Curious Questions: Why are pineapples called pineapples, when they're not pines and not apples?

Martin Fone delves into the curious history of one of the world's most popular tropical fruits.

Credit: Melanie Johnson

Why is pancake day called 'Shrove Tuesday'?

Martin Fone investigates how Shrove Tuesday got its name — and also unveils the history of the day that precedes it,

Curious Questions: Why does Scotland have 30,000 lochs, but only one lake?

A moment's reflection on a cancelled pub quiz gets Martin Fone wondering about Scotland's only lake.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.