Curious Questions: When did we first start playing cards?

Played with friends, family or in solitude, there are few things as familiar as a pack of cards. Yasha Beresiner takes a look at how we came to enjoy this form of entertainment — and how it's been spun out into everything from art to propaganda tool.

There are many claims to the origin of playing cards is lost in the mists of time. They have been attributed to China in the early 9th century — as so many items are when their origin is unknown — and to North Africa, specifically the Mamluks, in the 13th century.

Spain likes to claim their introduction to Europe, but early evidence suggests Flanders, France and Italy as the first countries in which playing cards, as we understand the term today, actually originated.

What is fascinating is the resilience and superstition of the card player, who, through the centuries, would not tolerate changes to the original structure of a pack of cards. From the earliest days, it consisted of four suit signs and a set number of cards.

The familiar English playing cards, with spades, hearts, diamonds and clubs, originate from France and trace their roots to about 1500. It was the Americans, however, who first adopted the concept of mirror images, which began in Portugal or Spain in the middle of the 19th century. Players across the pond are also credited with the invention of the Joker and the indices on the corners of the cards — a brilliant concept, as they allowed the player to see which cards he held by the smallest movement of his hand — which led to playing cards in the US being known as ‘squeezers’ during the early period of the 20th century.

As to the Joker, the 53rd card in a pack, it was the additional ‘Best Bower’ card used in the American game of Yuker that was corrupted to be named Joker and the popular image, in its many manifestations, followed the name.

Where playing cards become truly fascinating is when they deviate from the norm and, instead of the iconic and familiar kings and queens, depict recognisable reigning monarchs and their consorts or political figures, historical heroes and events. It is here that England excels in the production of some of the most interesting and early examples, prized among collectors.

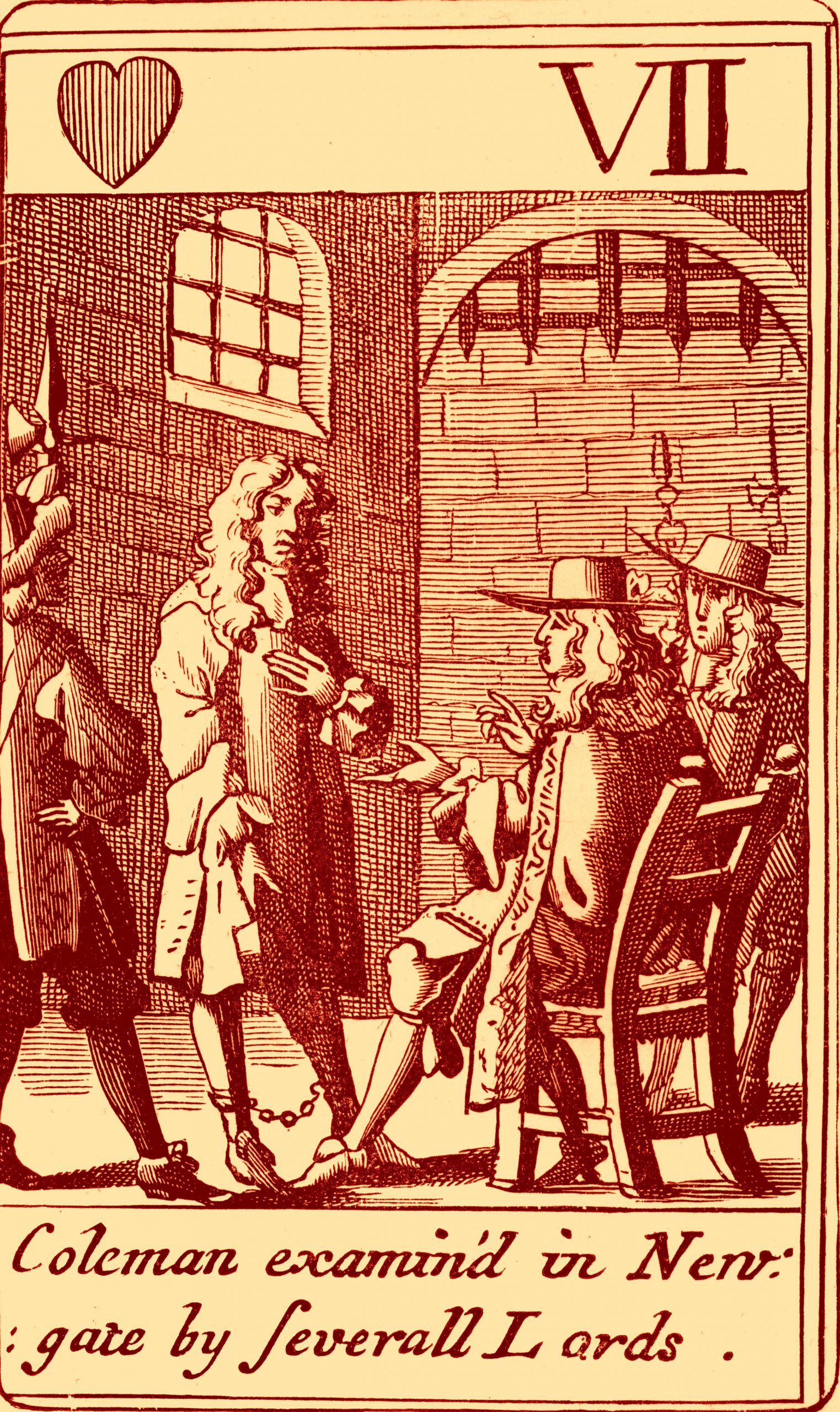

The potential of the playing card as a medium of communication, propaganda and education was not lost on our ancestors. In 1678, the infamous Rev Titus Oates claimed to have uncovered a Catholic conspiracy to kill Charles II. It was, of course, a fictitious event that became known as the Popish Plot. An enterprising artist came up with the rather lucrative idea that 52 images of the events might be well received by a generally illiterate, but card-playing public. Thus, Francis Barlow produced the narrative Popish Plot pack of cards, in which the illustration on each card tells the story.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Popish Plot cards were a great commercial success and other political packs followed through the centuries, right up to the present day. For the 1983 elections — the first in Britain when four parties were in contest — Gerald Scarfe and other well-known caricaturists designed Playing Politics or Cabinet Shuffle. A political pack of cards has been produced for most British elections since, culminating in a coalition deck issued to commemorate the UK general election in 2010.

For those who can’t stretch to the real thing, earlier decks have been beautifully reproduced by playing-card manufacturers. Today’s collector can have a very comprehensive view of early playing cards, through access to facsimiles often produced by the museums where the originals are housed.

There are many deviations of interest from the ordinary pack of cards. In Revolutionary France, having just decapitated the entire Royal Family, the Republicans found the ordinary pack offensive with its representation of crowned kings and queens and so, for a short time in 1793, packs appeared on the market with the crowns guillotined, until the publication of new-style, revolutionary cards. In a reflection of the superstitious, even obstinate character of the card player, however, the standard cards were reverted to by the early 1800s and the quaint revolutionary images are now curious rarities of a troubled period.

The most popular theme of all is the transformation card. These are cards where the pips (the symbols of each suit) have been incorporated into a picture drawn on the card. Any aspiring artist can try out his talent and ingenuity, remembering that the pips must not be moved from their established positions.

The first transformation cards were published by bookseller J. C. Cotta in Germany in 1805, who gave them as a Christmas gift to his clients. I’m sure he would turn in his grave if he knew the four-figure prices his packs now fetch at auction. Many transformation packs, some with dazzling colouring and masterful artwork, have followed suit.

Whichever style of pack you choose to play with, it’s reassuring to know that people have been playing games with cards for millennia. Any age group can join in and they offer a marvellous way to while away an hour of solitude.

Credit: Richard Cannon

How to win at Scrabble, by the world Scrabble champion

Country Life's Jeremy Taylor took on world Scrabble champion Brett Smitheram. This is what he learned.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

How to win at board games, from Monopoly and Cluedo to Scrabble and Snakes and Ladders

As millions of people around the country are set to have an enforced period at home, it'll be time to

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.